So the Viscount, not entertaining for more than a very few seconds the notion of conveying his protégée to Wolversham, had, in almost the same length of time, decided to place her in Miss Silverdale’s care until he should have run her grandfather to earth, and compelled him to honour his obligations. The only flaw to this scheme which he could perceive was the objection which Miss Silverdale’s mama might—and probably would—raise against it; but he had a comfortable belief in Miss Silverdale’s ability to bring her hypochondriacal parent round her thumb, and was thus able to set out for Inglehurst without fear of meeting with a rebuff.

However, he did feel that it might be prudent to warn Cherry that Lady Silverdale enjoyed indifferent health, and consequently indulged in rather odd humours, which found expression in fits of the blue-devils, a tendency to fancy herself ill-used, and a marked predilection for enacting what he called Cheltenham tragedies.

She listened to him attentively, and, to his surprise, seemed to derive encouragement from this somewhat daunting description of her prospective hostess. She said, with all the wisdom of one versed in the idiosyncrasies of invalids: “Then perhaps I can be of use in the house! Even Aunt Bugle says I am good at looking after invalids, and although I don’t wish to puff myself off I think that is perfectly true. In fact, I have been wondering if I shouldn’t seek for a post as attendant to an old, cantankersome lady: I daresay you know the sort of old lady I mean, sir!”

Lively memories of the tyranny exercised by his paternal grandmother over her family and her dependents crossed his mind, and he replied rather grimly: “I do, and can only trust that you will not be obliged to seek any such post!”

“Well,” she said seriously, “I own that it’s disagreeable to be pinched at for everything one does, but one must remember how much more disagreeable it must be to be old, and unable to do things for oneself. And also,” she added reflectively, “if a twitty old lady takes a fancy to one, one becomes valuable to her family. My aunt, and my cousins, were never so kind to me as during the months before poor old Lady Bugle died. Why, my aunt even said that she didn’t know how they would go on without me!”

She sounded so much gratified by this tribute that Desford bit back the caustic comment that sprang to the tip of his tongue, and merely said that Lady Silverdale was neither old nor dying; and although she would (in his opinion) wear down the patience of a saint it would be unjust to call her twitty.

When they reached their destination, they were received by Grimshaw, who showed no pleasure at sight of one who had run free at Inglehurst ever since he had been old enough to bestride a pony, but said dampingly that if my lady had known his lordship meant to visit her she would no doubt have set dinner back to suit his convenience. As it was, he regretted to be obliged to inform his lordship that my lady and Miss Henrietta had already retired to the drawing-room.

Too well-accustomed to the butler’s habitual air of disparaging gloom to be either surprised or offended the Viscount said: “Yes, I guessed how it would be, but I daresay her ladyship will forgive me. Be a good fellow, Grimshaw, and drop the word in Miss Hetta’s ear that I want to see her privately! I’ll wait in the library.”

Grimshaw might be proof against the Viscount’s smile but he was not proof against the lure of a golden coin slid into his hand. He did not demean himself by so much as a glance at it, but his experienced fingers informed him that it was a guinea, so he bowed in a stately way, and went off to perform the errand, not allowing himself to show his disapproval of Miss Steane by more than one look of outraged surprise.

The Viscount then led Miss Steane to a small saloon, and ushered her into it, telling her to sit down, like a good girl, and wait for him to bring Miss Silverdale to her. After that he withdrew to the library at the back of the hall, where, after a few minutes, he was joined by . Miss Silverdale, who came in, saying in a rallying tone: “Now, what’s all this, Des? What brings you here so unexpectedly? And why the mystery?”

He took her hands, and held them: “Hetta, I’m in a scrape!”

She burst out laughing. “I might have known it! And I am to rescue you from it?”

“And you are to rescue me from it,” he corroborated, the smile dancing in his eyes.

“What an unconscionable rogue you are!” she remarked, drawing her hands away, and disposing herself on a sofa. “I can’t conceive how I am to rescue you from the sort of scrapes you fall into, but sit down, and make a clean breast of it!”

He did so, telling his story without reservation. Her eyes widened a little, but she heard him in silence, until he reached the end of it, saying: “I would have taken her to Wolversham, but you know what my father is, Hetta! So there was nothing for it but to bring her to you!”

Then, at last, she spoke, shattering his confidence. “But I don’t think I can, Ashley!”

He stared incredulously. “But, Hetta—!”

“You can’t have considered!” she said. “If I know what your father is you should know just as well what my mother is! Her opinion of your Cherry’s exploit wouldn’t differ from his by so much as a hair’s breadth!”

“Oh, I know that!” he said. “I shan’t tell her the true story, stoopid! All I have to do is to say that my Aunt Emborough placed her in my charge, with instructions to deliver her into old Nettlecombe’s hands, but owing to his having misread the date—or the letter informing him of it having gone astray—or some such thing—he is still out of town, so that I was at my wits’ end to know what to do with the child.”

“And what,” she enquired conversationally, “will you say when she asks you why you didn’t rather place her in your mother’s care?”

He took a minute or two to find an answer to this poser, but finally produced, with considerable aplomb: “When I was at Wolversham, little more than a sennight since, I found my father quite out of curl, and Mama in too much of a worry about him to be troubled with a guest.”

She drew an audible breath. “You are not only a rogue, Des, but a Banbury man as well!”

He laughed: “No, no, how can you say so? There’s a great deal of truth in that part of the story, and you can scarcely expect me to tell your mother that if I were to walk in with Cherry on my arm my poor misguided Papa would instantly leap to the conclusion that I had not only fallen in love with her, but had brought her home in the hope that she would captivate him into bestowing his blessing on precisely the sort of match he most abominates. I daresay she might captivate him, for she’s a taking little thing, but hardly to that point!”

“Is she very pretty?” asked Miss Silverdale, keeping her fine eyes on his face.

“Yes, very, I think—even when dressed in cast-off garments which don’t become her, and with her hair in a tangle! Enormous eyes in a heart-shaped face, a mouth clearly made for kissing, and a great deal of innocent charm. Not in your style, but I fancy you’ll see what I mean when I present her to you. When I first saw her she looked to me to be scared out of her wits—which, half the time, she is, thanks to the Turkish treatment she has endured in her aunt’s house—but when she isn’t frightened she chatters away in the most engaging fashion, and has the merriest twinkle in her eyes. I think you will like her, Hetta, and I’m pretty sure your mother will. From what I gather she has a positive genius for waiting on—er—elderly invalids!” He paused, scanning her face. It was inscrutable, so, after a moment, he said coaxingly: “Come, now, Hetta! You can’t fail me! Good God, I’ve depended on you all my life! Yes, and if it comes to that, so have you depended on me—and have I ever failed you?”

A gleam of humour shone in her eyes. “You may have rescued me from scrapes when we were children,” she said, “but I haven’t been in a scrape for years!”

“No, but Charlie has!” he retorted. “You can’t deny that I’ve frequently rescued him, just because you begged me to!”

“Well, no,” she acknowledged. “And I can’t deny, either, that you have several times given me excellent advice on the management of the estate, but the thing which makes it so very awkward for me to do what you ask this time is that Charlie is at home! And if Miss Steane is so pretty, and so charming, he is bound to fall in love with her, for you know how often he tumbles into love!”

“Yes, and I also know how often he tumbles out of love! When I last saw him he was dangling after a lovely man-trap—thirty if she’s a day, and widowed a bare twelvemonth ago!”

“Mrs Cumbertrees,” she nodded. “But she has been a thing of the past for weeks, Des!”

“Then he is probably at the feet of some other dasher years older than he is himself. You may take it from me, Hetta, that there’s no need for you to be in a worry over the chance that he might take a fancy to Cherry: halflings rarely become nutty upon girls of their own age. In any event, she won’t be here long enough for Charlie to form a lasting passion for her! What’s he doing here, by the way? I thought he was going to Ireland, with a couple of choice spirits, in search of horses?”

“He was, but he had the misfortune to overturn his new highperch phaeton three days ago, and broke his head, and his arm, and two of his ribs,” said Miss Silverdale, in the voice of one inured to such misfortunes.

“Hunting the squirrel?” asked Desford, with mild interest.

“Very likely, though of course he doesn’t say so. He is still confined to his bed, for he was pretty knocked-up, but I don’t expect Mama will be able to prevail upon him to remain there for very much longer. He is already fretting to get up, which was why Mama was glad to see Simon drive up—Oh, good heavens! I quite forgot to tell you! I think you would wish to know that Simon has been dining with us, and is now sitting with Charlie! At least, he was when I came away from the drawing-room, but I daresay Mama has drawn him away by this time, for she said that she would only permit him to stay with Charlie for twenty minutes.”

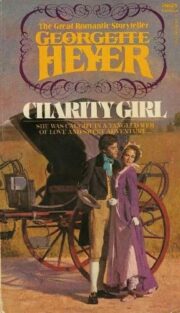

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.