“Shut your eyes!” he advised her, amused by her evident want of faith in his ability to avoid accident.

“No!” she said resolutely. “I must learn to accustom myself! Is it always so crowded in London, sir?”

“I am afraid it is often very much more crowded,” he said apologetically. “In fact, it is at the moment very empty!”

“And people choose to live here!” she shuddered.

He had turned back into Piccadilly some few minutes earlier, and now checked his horses for the turn into Arlington Street. “Yes. I am one of those very odd people, and I am taking you now to my house, so that you can rest and refresh before we continue our journey.”

She said uneasily: “I think I ought not to go to your house, sir. I may be a pea-goose but I do know that it is not the thing for females to visit gentlemen’s houses, and—and—”

“No, it is a trifle irregular,” he agreed, “but before we go any further there are certain arrangements I must make, and you would scarcely wish to wait in the street, would you? So the best thing I can do is to hand you over to my housekeeper for half-an-hour. I shall tell her that my Aunt Emborough placed you in my charge, and that I am taking you to your home, in Hertfordshire.”

She asked nervously: “Where—where are you taking me, if you please, sir?”

“Into Hertfordshire. I am going to ask an old and dear friend of mine to take care of you until I’ve found your grandfather. Her name is Miss Henrietta Silverdale, and she lives with her mother at a place called Inglehurst. Don’t look so scared! I am pretty sure you will like her, and entirely sure that she will be very kind to you.”

The curricle had come to a standstill outside one of the smaller houses on the east side of the street, and Stebbing had climbed down, and had gone to the horses’ heads. Miss Steane whispered: “It was wrong of me to run away, wasn’t it? I know it now, because everything has gone amiss, and—and I have only you to turn to for help in this scrape. But indeed, indeed, sir, I would never have asked you to carry me to London if I had known how it would be!”

He laid his hand over her tightly clenched ones, and said gently: “You are tired, my child, and the world looks black, doesn’t it? I can only say to you: Trust me! Haven’t I told you that I won’t abandon you?”

Her hands twisted under his, and clasped it convulsively. She said: “I never meant to be such a charge on you! Oh, pray believe me!”

“Oh, I know you didn’t! What you don’t know is that I don’t regard this adventure as a charge: I regard it as a challenge, and am determined to run your grandfather to earth if I have to go to all the watering-places in the land in search of him!” He saw that his butler had opened the door, and was coming towards the curricle, and disengaged his hand, saying: “Ah, here’s Aldham! Good-day to you, Aldham! Has Tain arrived yet?”

“Just an hour since, my lord,” replied Aldham, beaming fondly upon him, but casting a doubtful glance at his companion. He had known the Viscount since Desford’s cradle-days, having been employed at that time as page-boy at Wolversham, from which lowly position he had graduated by slow degrees to that of First Footman, and thence, in one longed-for leap, to the honourable post of butler to his young lordship; and he knew quite as much about him as did Stebbing, and rather more than did Tain, his lordship’s excellent valet, who was the only member of the little household in Arlington Street not born and bred at Wolversham. He could have named (had he not been the soul of discretion) every fair Cyprian with whom his volatile master had enjoyed amatory adventures, from the straw damsel who had caught his first, callow fancy, to the high flyer who had almost ruined him; and he had frequently officiated at far from respectable parties in Arlington Street. But he had never known the Viscount to drive up to the door, in broad daylight, with an unattended Young Female sitting beside him. His first impression, that the Viscount had brought home with him a country lightskirt, was dispelled by a second, covert look at Miss Steane: for one thing, she was no lightskirt; and for another the Viscount never seemed to take to very young females. To Aldham’s experienced eye she was more like a girl just broken out of the schoolroom—though what the Viscount was doing with any such was a problem beyond his power to solve.

But when he had been favoured with a glib explanation of her presence in the curricle he accepted it without even mental reservation. It was just like my Lady Emborough, he thought, to saddle my lord with a chit of a girl, with instructions to conduct her to her home in Hertfordshire, just as though it had been on the way from Hazelfield to London. And very much embarrassed the young lady was, by the looks of her! So he received her with a fatherly smile, and ushered her into the narrow hall of the house, saying that he would fetch up Mrs Aldham directly to wait upon her.

The Viscount lingered on the flagway to exchange words with the second of his chief mentors and well-wishers, the expression on whose face, compound of sorrow and censure, caused him to say: “Yes, you’ve no need to look at me like that—as though I didn’t know as well as you do that this is a rare case of pickles!”

“My lord,” said Stebbing very earnestly, “when I heard you tell Miss you was going to take her into Hertfordshire I was that comfumbuscated I pretty near fell off my seat, because it looked to me like you was going to take her to Wolversham!”

“No, I did think of doing so, but it wouldn’t answer,” replied the Viscount.

“No, my lord—as I would have taken the liberty of telling your lordship! As I beg leave to do now, for I wouldn’t be able to sleep easy in my bed if I didn’t, and it don’t signify if you choose to turn me off, because—”

“Of course it doesn’t signify! You wouldn’t go!” retorted the Viscount.

The corners of Stebbing’s grim mouth twitched involuntarily, but he refused to be beguiled. He said: “My lord, I’ve known you do some hey-go-mad things in your time, but you’ve never till this day done anything so cockle-brained as to make me think you must be short of a sheet! Which I do! My lord, you’re never going to take Miss to Inglehurst!”

“But I am,” asserted the Viscount. “Unless you can suggest where else I can take her?” He paused, regarding his henchman with mockery in his eyes. “You can’t, can you?”

“You hadn’t ought to have brought her to London at all!” muttered Stebbing.

“Very likely not, but it’s a waste of time to lay that in my dish now! I did bring her to London, and must now abide the consequence. Even you must own that to abandon her here would be the action of a damned ugly customer—which I am not, however hey-go-mad you may think me!” He saw that Stebbing was deeply troubled, and smiled, dropping a hand on his shoulder, and slightly shaking him. “Stubble it, you old rumstick! To whom else should I turn for help in this hobble than to Miss Hetta? Bless her, she’s never yet failed me! Good God, you should know how often we’ve rescued one another from scrapes!”

“When you was children!” Stebbing said. “That was different, my lord!”

“Not a bit of it! Stable the grays now, and tell the postilions I shall be needing them to carry me to Inglehurst within the hour. I’ll take my own chaise, but I shall have to hire horses: Ockley can be depended on to choose the right type, but warn him that I mean to return tonight. That’s all!”

He gave Stebbing no opportunity to utter any further protests, but turned on his heel, and went quickly into his house. Stebbing was left to address his embittered remarks to the weary gray at whose head he was standing before climbing into the curricle and driving it away.

Chapter 6

It was past seven o’clock when the Viscount’s beautifully sprung chaise reached Inglehurst, for although the journey had taken no more than three hours to accomplish he had not left Arlington Street until after four. Miss Steane, revived as much by the kindly and uncritical attitude of Mrs Aldham (yet another of those born on my Lord Wroxton’s wide estates) as by the tea with which she had been regaled, set forth in a tolerably cheerful mood, suppressing as well as she could the inevitable shrinking of a shy girl, who, realizing too late her imprudence, found herself without any other course open to her than to submit to her protector’s decree, and to allow him to thrust her into a household which consisted of a widow and her daughter who were wholly unknown to her. She could only hope that they would not resent her intrusion, or think her sunk beneath reproach for having behaved in a manner which she was fast becoming convinced was improper to the point of being unpardonable. Had she been able to think of an alternative to the Viscount’s plan she believed she would have embraced it thankfully, even had it been the offer of a post as cook-maid, but no alternative had presented itself to her, and the thought of being stranded in London, with only a few shillings in her purse, and not even the merest acquaintance to seek out in all that terrifying city, was not one she could face.

Something of what was in her mind the Viscount guessed, for although London held no terrors for him, and he had never been stranded anywhere with his pockets to let, neither his consequence nor his wealth had made him blind to the troubles that beset persons less comfortably circumstanced. He might be careless, and frequently rackety, but no one in dire straits had ever appealed to him for help in vain. His friends, and he had many friends, said of him that he was a great gun—true as touch—a right one; and even his severest critics found nothing worse to say of him than that it was high time he brought his carryings on to an end, and settled down. His father did indeed heap opprobrious epithets on him, but anyone unwise enough to utter the mildest criticism of his heir to my lord met with very short shrift. The Viscount was well aware of this; but while he did not doubt his father’s affection for him he was far too familiar with the Earl’s deep prejudices to introduce Miss Steane into his household. My lord was a rigid stickler, and it was useless to suppose that he would feel any sympathy with a young female who had behaved in a way which he would undoubtedly condemn as brass-faced. My lord’s views on propriety were clearly defined: male aberrations were pardonable; the smallest deviation from the rules governing the behaviour of females was inexcusable. He had placed no checks upon his sons, regarding (except when colic or gout had exacerbated his temper) their follies and amatory adventures with cynical amusement, but his daughter had never been allowed, until her marriage, to take a step beyond the gardens without a footman in attendance; and whenever she had gone on a visit to an approved friend or relative she had travelled in my lord’s carriage, accompanied not only by her footman and her maid but by a couple of outriders as well.

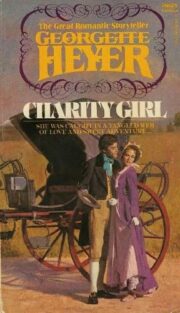

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.