“I am going to my grandfather,” she replied, a hint of defiance in her voice.

“Indeed! May I ask if he knows it?”

“Well—well, not yet!” she confessed.

He drew an audible breath, and said rather grimly: “Yes, well, we will postpone further discussion until we get to Farnborough, when I must hope to be able to convince you that this scheme of yours won’t do, my child!”

“You won’t convince me!” she said, betraying signs of agitation. “Oh, pray don’t try, sir! It is the only thing I can do! You don’t understand!”

“Then you shall explain it to me,” he said cheerfully.

She said no more, but groped in the folds of her cloak for the pocket which held her handkerchief. He was afraid that she was going to cry, and suffered a moment’s dismay. He was not chicken-hearted, but he found himself quite unable to face with equanimity the prospect of driving a lady in floods of tears along a busy post-road. However, she bravely suppressed all but one small sob, and did no more than blow her nose. He was moved to say, for her encouragement: “Good girl!” glancing down at her as he spoke, and smiling.

Of necessity it was a very brief glance, but as he turned his head back again to watch the road he caught a glimpse of the wavering, would-be valiant smile which answered his, and it wrung his heart.

In a few minutes Farnborough was reached, and he had drawn up in front of the Ship. Not many persons patronized this small post-house, so the landlord, who came out to welcome a recognizable member of the Quality, was saddened, but not surprised, when the Viscount, handing Miss Steane into his care, told him that they had stopped only to bait. “Anyone in the coffee-room?” he asked.

“No, sir, no one—not at the moment! But if your honour would wish to partake of refreshment in the private parlour—”

“No, the coffee-room will do very well. Some lemonade for the lady, and cold meat—cakes—fruit—whatever you have! And a tankard of beer for myself, if you please!” He looked down at Miss Steane, and said: “Go in, my dear: I’ll be with you in a moment.”

He watched her enter the inn, and turned to issue a few instructions to Stebbing, standing at the wheelers’ heads. Stebbing received these with a wooden: “Very good, my lord,” but the Viscount had taken barely two steps towards the door into the inn before his feelings overcame him, and he said, explosively: “My lord!”

“Well?” said the Viscount, over his shoulder.

“It ain’t my place to speak,” said Stebbing, with careful restraint, “but being as I’ve known your lordship ever since you was a little lad, which I taught to ride your first pony—ah, and pulled you out of scrapes! and being that—”

“You needn’t go on!” interrupted Desford, quizzing him. “I know just what you are trying to say! I must take care I don’t fall into yet another scrape, mustn’t I?”

“Yes, my lord, and I hope you will—though it don’t look to me, the way things is shaping, that you will!”

But Desford only laughed, and went into the inn. The mistress of the establishment had taken Miss Steane upstairs, and when she presently joined his lordship in the coffee-room she had washed her face, tidied her unruly hair, and was carrying her cloak over her arm. She looked much more presentable, but the round dress of faded pink cambric which she wore was rather crumpled, besides being muddied round the hem, and in no way became her. She was looking very grave, but when she saw the chicken, and the tongue, and the raspberries on the table her eyes brightened perceptibly, and she said gratefully: “Oh, thank you, sir! I am very much obliged to you! I ran away before breakfast, and you can’t think how hungry I am!”

She then sat down at the table, and proceeded to make a hearty meal. Desford, who was not at all hungry, sat watching her, his tankard in his hand, thinking that for all her nineteen years she was very little removed from childhood. While she ate he forbore to question her, but when she came to the end of her nuncheon, and said that she now felt much better, he said: “Do you feel sufficiently restored to tell me all about it? I wish you will!”

Her brightened eyes clouded, but after a slight hesitation she said: “If I tell you why I’ve run away, will you take me to London, sir?”

He laughed. “I am making no rash promises—except to carry you straight back to Maplewood if you don’t tell me!”

She said with quaint dignity, but as though she had a lump in her throat: “I cannot believe that you would do anything so—so unhandsome!”

“No, I am sure you cannot,” he said sympathetically. “But you must consider my position, you know! Recollect that all I know at this present is that although you told me last night that you were not very happy I am persuaded you had no intention then of running away. Yet today I come upon you, in a good deal of distress, having apparently reached a sudden decision to leave your aunt. Did you perhaps have a quarrel with her, fly up into the boughs, and run away without giving yourself time to consider whether she had really been unkind enough to warrant your taking such an extreme course? Or whether she too had lost her temper, and had said much more than she meant?”

She looked forlornly at him, and gave her head a shake. “We didn’t quarrel. I didn’t even quarrel with Corinna. Or with Lucasta. And it wasn’t such a sudden decision. I’ve wished desperately—oh, almost from the moment my aunt took me to Maplewood!—to escape. Only whenever I ventured to ask my aunt if she would help me to find a situation where I could earn my own bread she always scolded me for being ungrateful, and—and said I should soon wish myself back at Maplewood, because I was fit for nothing but a—a menial position.” She paused, and, after a moment or two, said rather hopelessly: “I can’t explain it to you. I daresay you wouldn’t understand if I could, because you have never been so poor that you were obliged to hang on anyone’s sleeve, and try to be grateful for a worn-out ribbon, or a scrap of torn lace which one of your cousins gave you, instead of throwing it away.”

“No,” he replied. “But you are mistaken when you say that I don’t understand. I have seen all too many of such cases as you describe, and have sincerely pitied the victims of this so-called charity, who are expected to give unremitting service to show their gratitude for—” He broke off, for she had winced, and turned away her face. “What have I said to upset you?” he asked. “Believe me, I had no intention of doing so!”

“Oh, no!” she said, in a stifled voice. “I beg your pardon! It was stupid of me to care for it, but that word brought it all back to me, like—like a stab! Lucasta said I was well-named, and my aunt s-said: ‘ Very true, my love!’ and that in future I should be called Charity, to keep me in mind of the fact that that is what I am—a charity girl!”

“What a griffin!” he exclaimed disdainfully. “But she won’t call you Charity, you know! Depend upon it, she wouldn’t wish people to think her spiteful!”

“They wouldn’t. Because it is my name!” she disclosed tragically. “I know I told you it was Cherry, but it wasn’t a fubbery, sir, to say that, because I have always been called Cherry.”

“I see. Do you know, I like Charity better than Cherry? I think it is a very pretty name.”

“You wouldn’t think so if it was your name, and true!”

“I suppose I shouldn’t,” he admitted. “But what did you do to bring down all this ill-will upon your head?”

“Corinna was on the listen last night, when we talked together on the stairs,” she said. “She is the most odious, humbugging little cat imaginable, and if you think I shouldn’t say such a thing of her I am sorry, but it is true! I was used to think her the most amiable of my cousins, and—and my friend! And even though I did know that she was a shocking fibster, and not in the least above carrying tales against Oenone to my aunt, I never dreamed she would do the same by me! Well—well, there was some excuse for her trying for revenge against Oenone, because Oenone is a very disagreeable girl, and for ever picking out grievances, and trying to set my aunt against her sisters. But—” Her eyes filled with tears, which she made haste to brush away—“she—she had no cause to do me a mischief! But—but she twisted everything I said to you, sir, m-making it seem quite different from what I did say! She even said that you wouldn’t have come upstairs if I hadn’t th-thrown out lures to you! Which I didn’t! I didn’t!”

“On the contrary! You begged me not to come upstairs!” he said, smiling.

“Yes, and so I told them, but neither my aunt nor Lucasta would believe me. They—they accused me of being a—a designing little squirrel, and my aunt read me a scold about g-girls like me ending up in the Magdalen: and when I asked her what the Magdalen is, she said that if I continued to make sheep’s eyes at every man that crossed my path I should very soon discover what it is. But I don’t, I don’t!”she said vehemently. “It wasn’t my fault that you came up to talk to me last night, and it wasn’t my fault that Sir John Thorley took me up in his chaise and so very kindly drove me back to Maplewood, the day he overtook me walking back from the village in the rain; and it wasn’t my fault that Mr Rainham came over to talk to me when I brought Dianeme and Tom down to the drawing-room one evening! I did not put myself forward! I sat down, just as my aunt bade me, in a chair against the wall, and made not the least push to keep him beside me! I promise you I didn’t, sir!” Her tears brimmed over, but she brushed them away, and said: “It was nothing but kindness on their parts, and to say that I lured either of them away from Lucasta is wickedly unjust!”

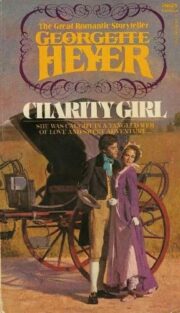

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.