‘What’s this?’ Luca asked, and pushed his way to the front of the crowd. Freize had the gate half-open and was admitting one person at a time on payment of a half-groat, chinking the coins in his hand.

‘What are you doing?’ Luca asked tersely.

‘Letting people see the beast,’ Freize replied. ‘Since there was such an interest, I thought we might allow it. I thought it was for the public good. I thought I might demonstrate the majesty of God by showing the people this poor sinner.’

‘And what made you think it right to charge for it?’

‘Brother Peter is always so anxious about the expenses,’ Freize explained agreeably, nodding at the clerk. ‘I thought it would be good if the beast made a contribution to the costs of his trial.’

‘This is ridiculous,’ Luca said. ‘Close the gate. People can’t come in and stare at it. This is supposed to be an inquiry, not a travelling show.’

‘People are bound to want to see it,’ Isolde observed. ‘If they think it has been threatening their flocks and themselves for years. They are bound to want to know it has been captured.’

‘Well, let them see it, but you can’t charge for it,’ Luca said irritably. ‘You didn’t even catch it, why should you set yourself up as its keeper?’

‘Because I loosed its bonds and fed it,’ Freize said reasonably.

‘It is free?’ Luca asked, and Isolde echoed nervously: ‘Have you freed it?’

‘I cut the ropes and got myself out of the pit at speed. Then it rolled about and crawled out of the nets,’ Freize said. ‘It had a drink, had a bite to eat, now it’s lying down again, resting. Not much of a show really, but they are simple people and not much happens here. And I charge half price for children and idiots.’

‘There is only one idiot here,’ Luca said severely. ‘And he is not from the village. Let me in, I shall see it.’ He went through the gate and the others followed him. Freize quietly took coins off the remaining villagers and opened the gate wide for them. ‘I’d wager it’s no wolf,’ he said quietly to Luca.

‘What do you mean?’

‘When it got itself out of the net I could see. It’s curled up now in the shadowy end, so it’s harder to make out, but it’s no beast that I have ever seen before. It has long claws and a mane, but it goes up and down from its back legs to all fours, not like a wolf at all.’

‘What kind of beast is it?’ Luca asked him.

‘I’m not sure,’ Freize conceded. ‘But it is not much like a wolf.’

Luca nodded and went towards the bear pit. There was a set of rough wooden steps and a ring of trestles laid on staging, so that spectators to the bear baiting could stand all around the outside of the pit and see over the wooden walls.

Luca climbed the ladder and moved along the trestle so that Brother Peter and the two girls and the little shepherd boy could get up too.

The beast was huddled against the furthest wall, its legs tucked under its body. It had a thick long mane, and a hide tanned dark brown from all weathers, discoloured by mud and scars. On its throat were two new rope burns; now and then it licked a bleeding paw. Two dark eyes looked out through the matted mane and, as Luca watched, the beast bared its teeth in a snarl.

‘We should tie it down and cut into the skin,’ Brother Peter suggested. ‘If it is a werewolf we will cut the skin and beneath it there will be fur. That will be evidence.’

‘You should kill it with a silver arrow,’ one of the villagers remarked. ‘At once, before the moon gets any bigger. It will be stronger then, they wax with the moon. Better kill it now while we have it and it is not in its full power.’

‘When is the moon full?’ Luca asked.

‘Tomorrow night,’ Ishraq answered. The little boy beside her took the aconite from his hat and threw it towards the curled animal. It flinched away.

‘There!’ someone said from the crowd. ‘See that? It fears wolfsbane. It’s a werewolf. We should kill it right now. We shouldn’t delay. We should kill it while it is weak.’

Someone picked up a stone and threw it. It caught the beast on its back and it flinched and snarled and shrank away as if it would burrow its way through the high wall of the bear pit.

One of the men turned to Luca. ‘Your honour, we don’t have enough silver to make an arrow. Would you have some silver in your possession that we might buy from you, and have forged into an arrowhead? We’d be very grateful. Otherwise we’ll have to send to Pescara, to the moneylender there, and it will take days.’

Luca glanced at Brother Peter. ‘We have some silver,’ he said cautiously. ‘Sacred property of the Church.’

‘We can sell it to you,’ Luca ruled. ‘But we’ll wait for the full moon before we kill the beast. I want to see the transformation with my own eyes. When I see it become a full wolf then we will know that it is the beast you report, and we can kill it when it is in its wolf form.’

The man nodded. ‘We’ll make the silver arrow now, so as to be ready.’ He went into the inn with Brother Peter, discussing a fair price for the silver, and Luca turned to Isolde and took a breath. He knew himself to be nervous as a boy.

‘I was going to ask you, I meant to mention it earlier, there is only one dining room here . . . in fact, will you dine with us tonight?’ he asked.

She looked a little surprised. ‘I had thought Ishraq and I would eat in our room.’

‘You could both eat with us at the large table in the dining room,’ Luca said. ‘It’s closer to the kitchen, the food would be hotter, fresher from the oven. There could be no objection.’

She glanced away, her colour rising. ‘I would like to . . .’

‘Please do,’ Luca said. ‘I would like your advice on . . .’ He trailed off, unable to think of anything.

She saw at once his hesitation. ‘My advice on what?’ she asked, her eyes dancing with laughter. ‘You have decided what to do with the werewolf, you will soon have orders as to your next mission. What can you possibly want with my opinion?’

He grinned ruefully. ‘I don’t know. I have nothing to say. I just wanted your company. We are travelling together, you and I, Brother Peter and Ishraq, Freize who has sworn himself to be your man – I just thought you might dine with us.’

She smiled at his frankness. ‘I shall be glad to spend this evening with you,’ she said honestly. She was conscious of wanting to touch him, to put her hand on his shoulder, or to step closer to him. She did not think it was desire that she felt; it was more like a yearning just to be close to him, to have his hand upon her waist, to have his dark head near to hers, to see his hazel eyes smile.

She knew that she was being foolish, that to be close to him, a novice for the priesthood, was a sin, that she herself was already in breach of the vows she had made when she had joined the abbey; and she stepped back. ‘Ishraq and I will come sweet-smelling to dinner,’ she remarked at random. ‘She has got the innkeeper to bring the bathtub to our room. They think we are madly reckless to bathe when it’s not even Good Friday – that’s when they all take their annual bath – but we have insisted that it won’t make us ill.’

‘I will expect you at dinner, then,’ he said. ‘As clean as if it was Easter.’ He jumped down from the platform and put out his hands to help her. She let him lift her down and as he put her on her feet he held her for a moment longer than was needed to make sure she was steady. He felt her lean slightly towards him, he could not have been mistaken; but then she stepped away and he was sure that he had been mistaken. He could not read her movements, he could not imagine what she was thinking, and he was bound by vows of celibacy to take no step towards her. But at any rate, she had said that she would come to dinner and she had said that she would like to dine with him. That at least he was sure of, as she and Ishraq went into the dark doorway of the inn.

Luca glanced up, self-consciously, but Freize had not observed the little exchange. He was intent on the werewolf as it turned around and around, as dogs do before they lie down. When it settled and did not move, Freize announced to the little audience, ‘There now, it’s gone to sleep. Show’s over. You can come back tomorrow.’

‘And tomorrow we’ll see it for free,’ someone claimed. ‘It’s our werewolf, we caught it, there’s no reason that you should charge us to see it.’

‘Ay, but I feed him,’ Freize said. ‘And my lord pays for his keep. And he will examine the creature and execute it with our silver arrow. So that makes him ours.’

They grumbled about the cost of seeing the beast as Freize shooed them out of the yard and closed the doors on them. Luca went into the inn and Freize to the back door of the kitchen.

‘D’you have anything sweet?’ he asked the cook, a plump dark-haired woman who had already experienced Freize’s most blatant flattery. ‘Or at any rate, d’you have anything half as sweet as your smile?’ he amended.

‘Get away with you,’ she said. ‘What are you wanting?’

‘A slice of fresh bread with a spoonful of jam would be very welcome,’ Freize said. ‘Or some sugared plums, perhaps?’

‘The plums are for the lady’s dinner,’ she said firmly. ‘But I can give you a slice of bread.’

‘Or two,’ Freize suggested.

She shook her head at him in mock disapproval but then cut two slices off a thick rye loaf, slapped on two spoonfuls of jam and stuck them face to face together. ‘There, and don’t be coming back for more. I’m cooking dinner now and I can’t be feeding you at the kitchen door at the same time. I’ve never had so many gentry in the house at one time before, and one of them appointed by the Holy Father! I have enough to do without you at the door night and day.’

‘You are a princess,’ Freize assured her. ‘A princess in disguise. I shouldn’t be surprised if someone didn’t come by one day and snatch you up to be a princess in a castle.’

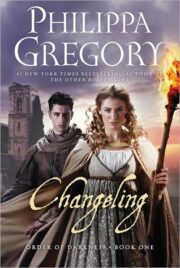

"Changeling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Changeling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Changeling" друзьям в соцсетях.