All afternoon they listened to stories of noises in the night, the handles of locked doors being gently tried, and losses from the herds of sheep which roamed the pastures under the guidance of the boys of the village. The boys reported a great wolf, a single wolf running alone, which would come out of the forest and snatch away a lamb that had strayed too far from its mother. They said that the wolf sometimes ran on all four legs, sometimes stood up like a man. They were in terror of it, and would no longer take the sheep to the upper pastures but insisted on staying near the village. One lad, a six-year-old shepherd boy, told them that his older brother had been eaten by the werewolf.

‘When was that?’ Luca asked.

‘Seven years ago, at least,’ the boy replied. ‘For I never knew him – he was taken the year before I was born, and my mother has never stopped mourning for him.’

‘What happened?’ Luca asked.

‘These villagers have all sorts of tales,’ Brother Peter said quietly to him. ‘Ten to one the boy is lying, or his brother died of some disgusting disease that they don’t want to admit.’

‘She was looking for a lamb, and he was walking with her as he always did,’ the boy said. ‘She told me that she sat down just for a moment and he sat on her lap. He fell asleep in her arms and she was so tired that she closed her eyes for only a moment, and when she woke he was gone. She thought he had strayed a little way from her and she called for him and looked all round for him but she never found him.’

‘Absolute stupidity,’ Brother Peter remarked.

‘But why did she think the werewolf had taken him?’ Luca asked.

‘She could see the marks of a wolf in the wet ground round the stream,’ the boy said. ‘She ran about and called and called, and when she could not find him she came running home for my father and he went out for days, tracking down the pack, but even he, who is the best hunter in the village, could not find them. That was when they knew it was a werewolf who had taken my brother. Taken him and disappeared, as they do.’

‘I’ll see your mother,’ Luca decided. ‘Will you ask her to come to me?’

The boy hesitated. ‘She won’t come,’ he said. ‘She grieves for him still. She doesn’t like to talk about it. She won’t want to talk about it.’

Brother Peter leaned towards Luca and spoke quietly to him. ‘I’ve heard a tale like this a dozen times,’ he said. ‘Likely the child had something wrong with him and she quietly drowned him in the stream and then came back with a cock-and-bull story to tell the husband. She won’t want to have us asking about it, and there’s no benefit in forcing the truth out of her. What’s done is done.’

Luca turned to his clerk and raised his papers so that his face was hidden from the boy. ‘Brother Peter, I am conducting an inquiry here into a werewolf. I will speak to everyone who has any knowledge of such a satanic visitor. You know that’s my duty. If along the way I discover a village where baby-killing has been allowed then I will inquire after that too. It is my task to inquire into all the fears of Christendom: everything – great sins and small. It is my task to know what is happening and if it foretells the end of days. The death of a baby, the arrival of a werewolf, these are all evidence.’

‘Do you have to know everything?’ Brother Peter demanded sceptically. ‘Can we let nothing go?’

‘Everything,’ Luca nodded. ‘And that is my curse that I carry just like the werewolf. He has to rage and savage. I have to know. But I am in the service of God and he is in the service of the Devil and is doomed to death.’

He turned back to the boy. ‘I’ll come to your mother.’

He got up from the table and the two men with the boy – still faintly protesting and crimson to his ears – led the way down the stairs and out of the inn. As they were going out of the front door, Isolde and Ishraq were coming down the stairs.

‘Where are you going?’ Isolde asked.

‘To visit a farmer’s wife, this young man’s mother,’ Luca said.

The girls looked at Brother Peter, whose face was impassive but clearly disapproving.

‘Can we come too?’ Isolde asked. ‘We were just going out to walk around.’

‘It’s an inquiry, not a social call,’ Brother Peter said.

But Luca said, ‘Oh, why not?’ and Isolde walked beside him, while the little shepherd boy, torn between embarrassment and pride at all the attention, went ahead. His sheepdog, which had been lying in the shadow of a cart outside the inn, pricked up its ears at the sight of him, and trotted at his heels.

He led them out of the dusty market square, up a small rough-cut flight of steps to a track that wound up the side of the mountain, following the course of a fast-flowing stream, and then stopped abruptly at a little farm, a pretty duck pond before the yard, a waterfall from the small cliff behind it. A ramshackle roof of ruddy tiles topped a rough wall of wattle and daub which had been lime-washed many years ago and was now a gentle buff colour. There was no glass in the windows but the shutters stood wide open to the afternoon sun. There were chickens in the yard and a pig with piglets in the walled orchard to the side. In the field beyond there were two precious cows, one with a calf, and as they walked up the cobbled track the front door opened and a middle-aged woman came out, her hair tied up in a scarf, a hessian apron over her homespun gown. She stopped in surprise at the sight of the wealthy strangers.

‘Good day to you,’ she said, looking from one to another. ‘What are you doing, Tomas, bringing such fine folks here? I hope he has been no trouble, sir? Can I offer you some refreshment?’

‘This is the man from the inn who brought the werewolf in,’ Tomas said breathlessly. ‘He would come to see you, though I told him not to.’

‘You shouldn’t have told him anything at all,’ she observed. ‘It’s not for small boys, small dirty boys, to speak with their betters. Go and fetch a jug of the best ale from the still room, and don’t say another word. Sirs, ladies – will you sit?’

She gestured to a bench set into the low stone wall before the house. Isolde and Ishraq took a seat and smiled up at her. ‘We rarely have company here,’ she said. ‘And never ladies.’

Tomas came out of the house carrying two roughly carved three-legged stools and put them down for Brother Peter and Luca, then dashed in again for the jug of small ale, one glass and three mugs. Bashfully, he offered the glass to Isolde and then poured ale for everyone else into mugs.

Luca and Brother Peter took their seats and the woman stood before them, one hand twisting her apron corner. ‘He is a good boy,’ she said again. ‘He wouldn’t mean to talk out of turn. I apologise if he offended you.’

‘No, no, he was polite and helpful,’ Luca said.

‘He’s a credit to you,’ Isolde assured her.

‘And growing very big and strong,’ Ishraq remarked.

The mother’s pride beamed out of her face. ‘He is,’ she said. ‘I thank the Lord for him every day of his life.’

‘But you had a previous boy.’ Luca put down his mug and spoke gently to her. ‘He told us that he had an older brother.’

A shadow came across the woman’s broad handsome face and she looked suddenly weary. ‘I did. God forgive me for taking my eye off him for a moment.’ At the thought of him she could not speak; she turned her head away.

‘What happened?’ Isolde asked.

‘Alas, alas, I lost him. I lost him in a moment. God forgive me for that moment. But I was a young mother and so weary that I fell asleep and in that moment he was gone.’

‘In the forest?’ Luca prompted.

A silent nod confirmed the fact.

Gently, Isolde rose to her feet and pressed the woman down onto the bench so that she could sit. ‘Was he taken by wolves?’ she asked quietly.

‘I believe he was,’ the woman said. ‘There were rumours of wolves in the woods even then, that was why I was looking for the lamb, hoping to find it before nightfall.’ She gestured at the sheep in the field. ‘We don’t have a big flock. Every beast counts for us. I sat down for a moment. My boy was tired so we sat to rest. He was not yet four years old, God bless him. I lay down with him for a moment and fell asleep. When I woke he was gone.’

Isolde put a comforting hand on her shoulder.

‘We found his little shirt,’ the woman continued, her voice trembling with unspoken tears. ‘But that was some months later. One of the lads found it when he was bird’s-nesting in the forest. Found it under a bush.’

‘Was there any blood on it?’ Luca asked.

She shook her head. ‘It was washed through by rain,’ she said. ‘But I took it to the priest and we held a service for his innocent soul. The priest said I should bury my love for him and have another child – and then God gave me Tomas.’

‘The villagers have captured a beast that they say is a werewolf,’ Brother Peter remarked. ‘Would you accuse the beast of murdering your child?’

He expected her to flare out, to make an accusation at once; but she looked wearily at him as if she had worried and thought about this for too long already. ‘Of course when I heard there was a werewolf I thought it might have taken my boy Stefan – but I don’t know. I can’t even say that it was a wolf that took him. He might have wandered far and fallen in the stream and drowned, or in a ravine, or just been lost in the woods. I saw the tracks of the wolves but I didn’t see my son’s footprints. I have thought about it every day of my life; and still I don’t know.’

Brother Peter nodded and pursed his lips. He looked at Luca. ‘Do you want me to write down her statement and have her put her mark on it?’

Luca shook his head. ‘Later we can, if we think there is need,’ he said. He bowed to the woman. ‘Thank you for your hospitality, goodwife. What name shall I call you?’

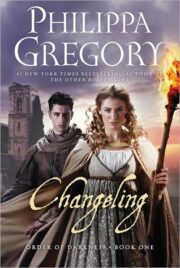

"Changeling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Changeling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Changeling" друзьям в соцсетях.