Ishraq was clinging on to the neck of her horse, exhausted and sick with her injury. Freize looked up at her. ‘She’s doing poorly. I’ll take her up before me.’

‘No,’ Isolde said. ‘Lift her up onto my horse. We can ride together.’

‘She can barely stay on!’

‘I’ll hold her,’ she said with firm dignity. ‘She would not want to be held by a man, it is against her tradition. And I would not like it for her.’

Freize glanced at Luca for permission and, when the young man shrugged, he got down from his own horse and walked over to where the slave swayed in the saddle.

‘I’ll lift you over to your mistress,’ he said to her, speaking loudly.

‘She’s not deaf! She’s just faint!’ Luca said irritably.

‘Both as stubborn as each other,’ Freize confided to the slave girl’s horse as her rider tumbled into his arms. ‘Both as stubborn as the little donkey, God bless him.’ Gently, he carried Ishraq over to Isolde’s horse and softly set her in the saddle and made sure that she was steady. ‘Are you sure you can hold her?’ he asked Isolde.

‘I can,’ she said.

‘Well, tell me if it is too much for you. She’s no lightweight, and you’re only a weakly little thing.’ He turned to Luca. ‘I’ll lead her horse. The others will follow us.’

‘They’ll stray,’ Luca predicted.

‘I’ll whistle them on,’ Freize said. ‘Never hurts to have a few spare horses, and maybe we can sell them if we need.’

He mounted his own steady cob, took the reins of Ishraq’s horse, and gave a low encouraging whistle to the other four horses who at once clustered around him, and the little cavalcade set off steadily down the road.

‘How far to the nearest town?’ Luca asked Brother Peter.

‘About eight miles, I think,’ he said. ‘I suppose she’ll make it; but she looks very sick.’

Luca looked back at Ishraq, who was leaning back against Isolde, grimacing in pain, her face pale. ‘She does. And then we’ll have to turn her over to the local lord for burning when we get there. We’ve rescued her from bandits and saved her from the Ottoman galleys to see her burned as a witch. I doubt she will think we have done her a kindness.’

‘She should have been burned as a witch yesterday,’ Brother Peter said unsympathetically. ‘Every hour is a gift to her.’

Luca reined back to bring his horse up alongside Isolde. ‘How was she injured?’

‘She took a blow from a cudgel while she was trying to defend us. She’s a clever fighter usually, but there were four of them. They jumped us on the road trying to steal from us and when they saw we were women without guards they thought to take us for ransom.’ She shook her head as if to rid herself of the memory. ‘Or for the galleys.’

‘They didn’t –’ he tried to find the words ‘– er, hurt you?’

‘You mean, did they rape us?’ she asked, matter-of-factly. ‘No, they were keeping us for ransom and then they got drunk. But we were lucky.’ She pressed her lips together. ‘I was a fool to ride out without a guard. I put Ishraq in danger. We’ll have to find someone to travel with.’

‘You won’t be able to travel at all,’ Luca said bluntly. ‘You are my prisoners. I am arresting you under charges of witchcraft.’

‘Because of poor Sister Augusta?’

He blinked away the picture of the two young women, bloodied like butchers. ‘Yes.’

‘When we get to the next town and the doctor sees Ishraq, will you listen to me, before you hand us over? I will explain everything to you, I will confess everything that we have done and what we have not done, and you can be the judge as to whether we should be sent back to my brother for burning. For that is what you will be doing, you know. If you send me back to him, you will sign my death warrant. I will have no trial worth the writing, I will have no hearing worth the listening. You will send me to my death. Won’t that sit badly on your conscience?’

Brother Peter brought his horse alongside. ‘The report has gone already,’ he said with dour finality. ‘And you are listed as a witch. There is nothing that we can do but release you to the civil law.’

‘I can hear her,’ Luca said irritably. ‘I can hear her out. And I will.’

She looked at him. ‘The woman you admire so much is a liar and an apostate,’ she said bluntly. ‘The Lady Almoner is my brother’s lover, his dupe, and his accomplice. I would swear to it. He persuaded her to drive the nuns mad and blame it on me so that you would come and destroy my rule at the abbey. She was his fool and I think you were hers.’

Luca felt his temper flare at being called a fool by this girl, but gritted his teeth. ‘I listened to her when you would not deign to speak to me. I liked her when you would not even show me your face. She swore she would tell the truth when you were – who knows what you were doing? At any rate, I had nothing to compare her with. But even so I listened out for her lies, and I understood that she was putting the blame on you when you did not even defend yourself to me. You may call me a fool – though I see you were glad enough for my help back there with the bandits – but I was not fooled by her – whatever you say.’

She bowed her head, as if to silence her own hasty words. ‘I don’t think you are a fool, Inquirer,’ she said. ‘I am grateful to you for saving us. I shall be glad to explain my side of this to you. And I hope you will spare us.’

The physician called to the Moorish slave as they rested in the little inn in the small town pronounced her bloodied and bruised but no bones broken. Luca paid for the best bed for her and Isolde, and paid extra for them not to have to share the room with other travellers.

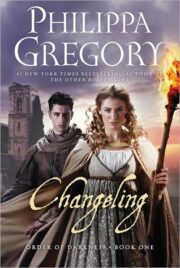

"Changeling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Changeling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Changeling" друзьям в соцсетях.