She sat; but she did not put back her hood, so Luca found he was forced to bend his head to peer under it to try to see her. In the shadow of the hood he could make out only a heart-shaped jaw line with a determined mouth. The rest of her remained a mystery.

‘Will you put back your hood, Lady Abbess?’

‘I would rather not.’

‘The Lady Almoner faced us without a hood.’

‘I was made to swear to avoid the company of men,’ she said coldly. ‘I was commanded to swear to remain inside this order and not meet or speak with men except for the fewest words and the briefest meeting. I am obeying the vows I was forced to take. It was not my choice, it was laid upon me by the Church. You, from the Church, should be pleased at my obedience.’

Brother Peter tucked his papers together and waited, pen poised.

‘Would you tell us of the circumstances of your coming to the nunnery?’ Luca asked.

‘They are well-enough known,’ she said. ‘My father died three and a half months ago and left his castle and his lands entirely to my brother, the new lord, as is right and proper. My mother was dead, and to me he left nothing but the choice of a suitor in marriage or a place in the abbey. My brother, the new Lord Lucretili, accepted my decision not to marry and did me the great favour of putting me in charge of this nunnery, and I came in, took my vows, and started my service as their Lady Abbess.’

‘How old are you?’

‘I am seventeen,’ she told him.

‘Isn’t that very young to be a Lady Abbess?’

The half-hidden mouth showed a wry smile. ‘Not if your grandfather founded the abbey and your brother is its only patron, of course. The Lord of Lucretili can appoint who he chooses.’

‘You had a vocation?’

‘Alas, I did not. I came here in obedience to my brother’s wish and my father’s will. Not because I feel I have a calling.’

‘Did you not want to rebel against your brother’s wish and your father’s will?’

There was a moment of silence. She raised her head and from the depth of her hood he saw her regard him thoughtfully, as if she were considering him as a man who might understand her.

‘Of course, I was tempted by the sin of disobedience,’ she said levelly. ‘I did not understand why my father would treat me so. He had never spoken to me of the abbey nor suggested that he wanted a life of holiness for me. On the contrary, he spoke to me of the outside world, of being a woman of honour and power in the world, of managing my lands and supporting the Church as it comes under attack both here and in the Holy Land. But my brother was with my father on his deathbed, heard his last words, and afterwards he showed me his will. It was clearly my father’s last wish that I come here. I loved my father, I love him still. I obey him in death as I obeyed him in life.’ Her voice shook slightly as she spoke of her father. ‘I am a good daughter to him; now as then.’

‘They say that you brought your slave with you, a Moorish girl named Ishraq, and that she is neither a lay sister nor has she taken her vows.’

‘She is not my slave; she is a free woman. She may do as she pleases.’

‘So what is she doing here?’

‘Whatever she wishes.’

Luca was sure that he saw in her shadowed eyes the same gleam of defiance that the slave had shown. ‘Lady Abbess,’ he said sternly. ‘You should have no companions but the sisters of your order.’

She looked at him with an untameable confidence. ‘I don’t think so,’ she said. ‘I don’t think you have the authority to tell me so. And I don’t think that I would listen to you, even if you said that you had the authority. As far as I know there is no law that says a woman, an infidel, may not enter a nunnery and serve alongside the nuns. There is no tradition that excludes her. We are of the Augustine order, and as Lady Abbess I can manage this house as I see fit. Nobody can tell me how to do it. If you make me Lady Abbess then you give me the right to decide how this house shall be run. Having forced me to take the power, you can be sure that I shall rule.’ The words were defiant, but her voice was very calm.

‘They say she has not left your side since you came to the abbey?’

‘This is true.’

‘She has never gone out of the gates?’

‘Neither have I.’

‘She is with you night and day?’

‘Yes.’

‘They say that she sleeps in your bed?’ Luca said boldly.

‘Who says?’ the Lady Abbess asked him evenly.

Luca looked down at his notes, and Brother Peter shuffled the papers.

She shrugged, as if she were filled with disdain for them and for their gossipy inquiry. ‘I suppose you have to ask everybody, everything that they imagine,’ she said dismissively. ‘You will have to chatter like a clattering of choughs. You will hear the wildest of talk from the most fearful and imaginative people. You will ask silly girls to tell you tales.’

‘Where does she sleep?’ Luca persisted, feeling a fool.

‘Since the abbey became so disturbed she has chosen to sleep in my bed, as she did when we were children. This way she can protect me.’

‘Against what?’

She sighed as if she were weary of his curiosity. ‘Of course, I don’t know. I don’t know what she fears for me. I don’t know what I fear for myself. In truth, I think no-one knows what is happening here. Isn’t this what you are here to find out?’

‘Things seem to have gone very badly wrong since you came here.’

She bowed her head in silence for a moment. ‘Now that is true,’ she conceded. ‘But it is nothing that I have deliberately done. I don’t know what is happening here. I regret it very much. It causes me, me personally, great pain. I am puzzled. I am . . . lost.’

‘Lost?’ Luca repeated the word that seemed freighted with loneliness.

‘Lost,’ she confirmed.

‘You don’t know how to rule the abbey?’

Her head bowed down as if she were praying again. Then a small silent nod of her head admitted the truth of it: that she did not know how to command the abbey. ‘Not like this,’ she whispered. ‘Not when they say they are possessed, not when they behave like madwomen.’

‘You have no vocation,’ Luca said very quietly to her. ‘Do you wish yourself on the outside of these walls, even now?’

She breathed out a tiny sigh of longing. Luca could almost feel her desire to be free, her sense that she should be free. Absurdly, he thought of the bee that Freize had released to fly out into the sunshine, he thought that every form of life, even the smallest bee, longs to be free.

‘How can this abbey hope to thrive with a Lady Abbess who wishes herself free?’ he asked her sternly. ‘You know that we have to serve where we have sworn to be.’

‘You don’t.’ She rounded on him almost as if she were angry. ‘For you were sworn to be a priest in a small country monastery; but here you are – free as a bird. Riding around the country on the best horses that the Church can give you, followed by a squire and a clerk. Going where you want and questioning anyone. Free to question me – even authorised to question me, who lives here and serves here and prays here, and does nothing but sometimes secretly wish . . .’

‘It is not for you to pass comment on us,’ Brother Peter intervened. ‘The Pope himself has authorised us. It is not for you to ask questions.’

Luca let it go, secretly relieved that he did not have to admit to the Lady Abbess his joy at being released from his monastery, his delight in his horse, his unending insatiable curiosity.

She tossed her head at Brother Peter’s ruling. ‘I would expect you to defend him,’ she remarked dismissively. ‘I would expect you to stick together, as men do, as men always do.’

She turned to Luca. ‘Of course, I have thought that I am utterly unsuited to be a Lady Abbess. But what am I to do? My father’s wishes were clear, my brother orders everything now. My father wished me to be Lady Abbess and my brother has ordered that I am. So here I am. It may be against my wishes, it may be against the wishes of the community. But it is the command of my brother and my father. I will do what I can. I have taken my vows. I am bound here till death.’

‘You swore fully?’

‘I did.’

‘You shaved your head and renounced your wealth?’

A tiny gesture of the veiled head warned him that he had caught her in some small deception. ‘I cut my hair, and I put away my mother’s jewels,’ she said cautiously. ‘I will never be bare-headed again, I will never wear her sapphires.’

‘Do you think that these manifestations of distress and trouble are caused by you?’ he asked bluntly.

Her little gasp revealed her distress at the charge. Almost, she recoiled from what he was saying, then gathered her courage and leaned towards him. He caught a glimpse of intense dark blue eyes. ‘Perhaps. It is possible. You would be the one to discover such a thing. You have been appointed to discover such things, after all. Certainly I don’t wish things as they are. I don’t understand them, and they hurt me too. It is not just the sisters, I too am—’

‘You are?’

‘Touched,’ she said quietly.

Luca, his head spinning, looked to Brother Peter, whose pen was suspended in midair over the page, his mouth agape.

‘Touched?’ Luca repeated wondering wildly if she meant that she was going insane.

‘Wounded,’ she amended.

‘In what way?’

She shook her head as if she would not fully reply. ‘Deeply,’ was all she said.

There was a long silence in the sunlit room. Freize outside, hearing the voices cease their conversation, opened the door, looked in, and received such a black scowl from Luca that he quickly withdrew. ‘Sorry,’ he said as the door shut.

‘Should not the nunnery be put into the charge of your brother house, the Dominicans?’ Peter asked bluntly. ‘You could be released from your vows and the head of the monastery could rule both communities. The nuns could come under the discipline of the Lord Abbot, the business affairs of the nunnery could be passed to the castle. You would be free to leave.’

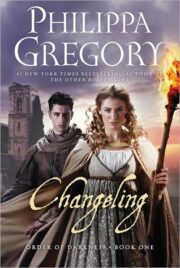

"Changeling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Changeling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Changeling" друзьям в соцсетях.