Edward was curious to know about Harville’s chosen bride, and I satisfied him as to her character and habits as soon as I had changed out of my wet clothes.

When I had done, he remarked that, in my absence, we had been invited to a picnic, and that he had accepted on both our behalfs.

Saturday 26 July

I am getting to know the neighbouring countryside very well, and already I feel quite at home here. I had my ride this morning before breakfast, as usual, and, later on, I paid some morning calls. After lunch I went into town for a new hat. I had a faint hope that I might see Miss Anne Elliot. I have seen little of her recently, for she has not attended any gatherings at which Edward and I have been present—they have not been smart enough for the Elliots—but I did not have the good fortune to come across her.

Tuesday 29 July

I saw Miss Anne this evening and I was surprised to discover how much I had missed her company.

I was about to ask her if I could escort her in to dinner when, unluckily, my hostess asked me to escort Miss Barnstaple instead. I bowed, and declared myself delighted, but although Miss Barnstaple was an engaging companion, my eyes were constantly drawn to Miss Anne.

She was seated next to a young man who looked to be a perfect fool, the sort who would not know a mast from a yard-arm. I thought she looked bored, but to my surprise, Miss Barnstaple said, ‘Anne seems to be finding her partner amusing. He is much liked by the ladies, not surprisingly, for he is very handsome.’

I was not struck by his looks myself, for they seemed too soft to me, and his conversation, snatches of which reached me in quiet moments, did not seem to be anything very remarkable. But I could not say so, for Miss Barnstaple might have construed my remarks—quite wrongly—as jealousy.

I could not help my eyes being drawn to his group from time to time, though, and I was gratified to find that Miss Anne’s gaze sought me out on more than one occasion. This small circumstance raised my spirits and allowed me to flatter myself that she would rather be talking to me.

As soon as supper was over, dancing was announced, and I went over to her and asked for the pleasure. She smiled, declared herself delighted, and put her hand in mine. I felt a sense of pride as I led her towards the set that was then forming. It was small, for the room only had space enough for five couples, but I was glad of the opportunity it gave me to talk to her.

‘I have not seen you for ...’ I was going to give an exact number of days, when I thought it might seem too particular, so I said, ‘... a while. Have you been mistaken for Napoleon again in the meantime?’

‘No, not recently,’ she said, as the music began. ‘Miss Scott has seen very little of the newspapers, and has grown calmer as a consequence, so that she is able to think of other things. Only yesterday she told me she had planted three new shrubs in the garden.’

‘Then you have escaped being attacked with the poker.’

‘For the time being, until the next newspaper arrives,’ she said. The dance parted us, but when it brought us back together again, she went on, ‘You have been away, visiting a friend, I understand?’

I was pleased to know that she had noticed my absence, and I began to tell her about Harville. As I related his plans, for the first time it did not seem so strange to me that he had chosen to shackle himself at an early age, and I supposed the change in my opinion must mean I was getting used to the idea; either that, or, having met his Harriet, I thought they would be happy together.

When I had finished telling her about Harville, I asked her casually, ‘Who was the young man you were sitting next to at dinner? I do not believe I know him.’

‘That was Mr Charles Musgrove,’ she said.

‘And is he a particular friend of yours?’ I could not help asking.

‘His family and mine are closely acquainted. The Musgroves live at the Great House at Uppercross.’

‘Ah, a family friend,’ I said, relieved. ‘I remember his parents,’ I continued, feeling suddenly in charity with young Mr Musgrove, and inclined to be expansive. ‘I overheard them once, talking about another son of theirs, Dick. Do they have any other children?’

‘Yes, they do, but they are all younger than Charles, and still in the schoolroom.’

As we talked, I noticed a well-dressed woman at the far side of the room, who was watching me with unfriendly eyes. I was surprised, and turned away, but I was conscious of her eyes on me for the rest of the dance.

When it was over, I reluctantly relinquished Miss Anne’s hand and returning to my brother, asked him, ‘Who is that lady?’

‘Which one?’

‘The one over there, on the other side of the room, well dressed, in an amber silk. Do you see her? She has been watching me as a captain watches an unpromising midshipman, and I am sure I cannot think why. It is impossible for me to have offended her in any way, for I do not know her, indeed I have never spoken to her in my life.’

His eyes turned towards her, and he said, ‘That is Lady Russell.’

‘The widow who was destined by her friends to marry Sir Walter Elliot, after his wife died?’ I asked.

My brother nodded.

I was thoughtful, but still could not think why she had been watching me with hostility.

‘I could understand her looking at me like that if I was Miss Cordingale or some other young beauty, and was intent on stealing Sir Walter away from her,’ I said, ‘but as that is not the case, I cannot think what she is about.’

‘Can you not? Then I will tell you. She is an old friend of the Elliot family, indeed, she was Lady Elliot’s best friend, and she is Miss Anne’s godmother. She has taken an interest in the Elliot girls for the last five years, since Lady Elliot’s untimely death, and she is especially fond of Anne, who favours Lady Elliot in both appearance and character. She is concerned that you are paying her too much attention.’

‘Ah, I see, she is worried that my intentions are not honourable,’ I said, understanding the dark looks she had been casting in my direction.

‘Quite the contrary, she is worried that your attentions are honourable. She wants something better than a commander for her god-daughter.’

I was affronted, but quickly came about.

‘She need have no fear. I do not have marriage in mind,’ I remarked, although, as I said it, I thought there would be worse fates than to marry Miss Anne Elliot.

‘Then I would advise you to be more circumspect. You are singling Miss Anne out for your attentions, and it will soon be noticed by other eyes than mine. You must not make her the subject of gossip, Frederick.’

‘I have scarcely seen her this last fortnight,’ I protested.

‘But you are making up for it this evening.’

‘I have danced with her only once, and I sat next to Miss Barnstaple at supper.’

‘But you did not look at Miss Barnstaple as you look at Miss Anne, with such absorption. No, do not bite my head off,’ he said, as I began to protest, ‘all I am saying is that you should take care. You are not on the high seas now, but in a country village, and you must be careful of her reputation.’

‘I will avoid her for a week, if that is what you wish,’ I said jovially.

‘It might be sensible,’ my brother said.

I had not expected him to agree, for I had spoken in jest, and I felt all the irritation of a person who has to carry through a promise that was not made in earnest. I had to watch Miss Anne accept the hand of Mr Charles Musgrove, and had to offer my own hand to several other young ladies who interested me not at all, in order to reassure my brother—and Lady Russell, whose eyes still turned towards me from time to time.

One such partner was Miss Elliot. I could not help thinking that an Elizabeth was a poor substitute for an Anne, but she was presented to me as a partner in such a way that neither of us could refuse, and it was difficult to know which of us felt they had made the worse bargain: Miss Elliot, who was forced to dance with a sailor, or I, who was unable to prevent myself from comparing Miss Elliot with her far more agreeable sister.

However, I achieved my purpose, for I had protected Miss Anne from gossip, and Lady Russell eventually looked away.

‘Lady Russell does not seem to watch Miss Elliot as jealously as she watches her sister,’ I remarked to my brother, when the dance was over. ‘She seems to have no apprehensions there. I suppose it is because Miss Elliot would never condescend to join herself to a mere sailor?’

‘That, and the fact that Miss Elliot is self-destined for the heir presumptive, William Walter Elliot, Esq.’

‘Ah, I see. By marrying him, she will retain her position as the first lady of the neighbourhood, and she will also retain her home on her father’s death. And does the heir presumptive know of her plan?’

‘He must have some idea, for Sir Walter and Miss Elliot have twice sought him out in London, whither they bend their steps every spring. On each occasion, they invited him to Kellynch Hall. His coming was spoken of as a certainty the first time, and we all looked forward to seeing him here. We were eager to meet him, for it would have fuelled many a pleasant evening’s conversation, when there was little else to talk about. The gentlemen could have contented themselves with talking over his habits, whilst the young ladies’ mothers could have put all their ingenuity into schemes for taking him away from Miss Elliot. It was the dearest wish of all of them that they should secure him for one or the other of their daughters. But alas, he disappointed us all, and he did not come. He was invited again the following year, but again he did not arrive. I do not believe Miss Elliot has quite despaired of him, nor do I believe she will, not until she knows him to be lost forever by virtue of his taking another to wife. But he does not seem to be in any hurry to visit Kellynch Hall.’

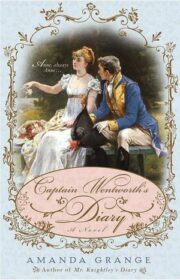

"Captain Wentworth’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.