‘Have you anything else to add?’

‘I would not object to a stretch of river, and a fine library.’

‘And a house in town as well, I suppose.’

He laughed, and said that if he was dreaming, he might as well do it in style.

‘Even so, I wish you might find promotion, and find it soon. Is there no one to speak for you?’ I asked.

‘The bishop is a friend of Melchester’s wife—you remember Melchester? We were at Cambridge together.’

‘Yes, I remember him. A stout fellow, with a liking for port. So will the bishop speak for you, do you think?’

‘He will if he can, but he has his own relatives to think of first, and two of them have entered the church. So you see, it is not very promising.’

‘And is there nothing you might do on your own account?’

‘I am doing all I can. There are one or two possibilities. Mr Abbott, the curate of Leigh Ings, has just been given a living by one of his cousins, and I believe I have a chance of adding the vacant curacy to my own. The duties are light, and it would mean an increase in my stipend. There is also the possibility of a living in Trewithing becoming available, and as there is no one waiting for it, it might fall to me.’

I expressed the hope that it would be so, and then I set about making my arrangements for visiting Harville. I am looking forward to meeting Harriet, and seeing what sort of woman has won the heart of my friend.

Wednesday 16 July

We dined with the Grayshotts this evening, and after dinner the ladies entertained us with music. Miss Denton was persuaded to perform by her mother, and proved herself a great proficient. After being encouraged by her mother to play a second sonata, she relinquished the stool, entreating Miss Anne to play. More hesitantly, Miss Anne approached the instrument. Her father looked up as she began to play and I thought here, at last, was some evidence of paternal feeling, but he turned his attention back to his conversation and continued to talk through her performance. Miss Elliot did not even do that much, and never once glanced in her sister’s direction.

As Miss Anne’s song continued, I was drawn over to the pianoforte, for her voice was sweet and her playing showed a superior taste. I listened with pleasure, and when she had done, I asked her to favour us again. She looked surprised, then she flushed with gratification and began another song. I sang with her, and we entertained ourselves as well as others.

Friday 18 July

I went into town this morning, and on my return I happened to pass a small house, from which came the sound of wailing. I hesitated, but upon hearing Miss Anne’s voice coming from inside I went in, and a strange scene met my eyes. A buxom woman was sitting in the corner of the room with her apron over her head, whilst seven children were rioting by the hearth. Miss Anne, having evidently just arrived, was speaking quietly but firmly to the children, who, it became plain, were arguing over a scrap of a puppy.

She picked the puppy up and cradled it in her arms, for it had been overwhelmed by the boisterous children. The older children jumped at it, but she reprimanded them until they stood quietly, then she soothed the younger children, who were in tears, and spoke bracingly to the woman, who, at last, emerged from behind her apron.

Within a few minutes harmony was restored, or what appeared to pass for harmony in the house, the puppy was placed in the loving arms of the youngest child, and Miss Anne and the woman had the luxury of looking round. This had the unwelcome effect of making my presence noticed.

‘I heard a commotion, and wondered if I could be of any assistance,’ I explained.

The woman said there was never a commotion in her house, I apologized, and I was about to leave when it transpired that Miss Anne was going into the village, and that the eldest girl was to go there also. I offered to escort them, they accepted my offer, and we set out together. The girl soon trailed behind, for which I was not sorry, as it meant I was able to talk freely to Miss Anne. I told her of my forthcoming visit to see Harville.

‘We were at the Naval Academy in Portsmouth together,’ I said. ‘Two young boys, eager to be at sea. I can hardly believe it is ten years since I went there, at the tender age of thirteen.’

‘You must have made many friends there,’ she said.

‘Yes, I did,’ I told her. ‘Benwick, Jenson and Harville. Benwick was younger than the rest of us, joining the academy later, in 1797, but somehow he became one of us. Not that we stayed in the academy all the time. We were put on board ships to gain experience, and very valuable it was.’

‘It sounds exciting,’ said Anne. ‘Very different from my own schooldays.’

She asked me about my training, and about my time as a midshipman, and then she told me about her times at school: her lessons, her masters, her friends—Miss Vance, who had returned to Cornwall to live with her parents; Miss Hamilton, who had married a Mr Smith and gone to live a life of gaiety in London; and Miss Donner, who had married a country squire.

At last we reached the village. I made my bow and left the ladies, returning home to lunch.

Tuesday 22 July

I set out early and arrived at Harville’s this afternoon. Harville greeted me warmly, and could not wait to introduce me to Harriet.

I found her to be a taking young thing, without the intelligence of Miss Anne Elliot, perhaps, and without her dark eyes, but pretty all the same. She seemed to be a degree or two less polished than Harville, but she was evidently very much in love with him, and I was glad to wish him all the happiness the occasion demanded.

I had little chance to talk to him of anything else, for when we returned to his lodgings, he would do nothing but sing Harriet’s praises. In vain did I try to talk to him about our adventures, past and future, for after answering a question sensibly, he would then sigh, and say that Harriet had the prettiest eyes or the tiniest feet or the tenderest heart, and I spoke about battles in vain. I laughed at him for it, but he only bade me wait until I was in love, whereupon I remarked that if love made such fools of men, I would sooner not succumb. He smiled, and said he pitied me, and then said that Harriet’s smile was brighter than the sun.

‘You have missed your vocation. You should have been a poet,’ I told him.

‘Perhaps I will become one yet!’ he said. ‘I am sure poets have an easier time of it than sailors.’

‘Though the pay is even worse,’ I said.

He laughed, and said that, on consideration, he would remain with the Navy.

I tried to go to bed three times, but he would not stop talking, and it was late before I returned to my chamber. I fear I will have little rational conversation over the next few days!

Wednesday 23 July

Harville took great delight in seeing me with his friends and family, and I took no less delight in their company. I had not seen them for three years, and, with regard to his sister Fanny, it was longer, for she was at school the last time I visited. Her appearance was a surprise, for she was no longer a child but a young woman, and a very superior young woman at that. Her mind was cultivated and her wits quick. Her face and figure were such that I knew she would soon have many admirers, and I said as much to Harville.

He seemed much pleased, and to begin with I took it as nothing more than brotherly pride, but as the day wore on, I began to think it might have something more at its root, for when we went out for a stroll, Harville and his family gradually fell behind until I was walking ahead with Fanny alone.

Again, when we returned to the house, there were occasions when we found ourselves sitting alone, on account of the others moving to the far end of the room. In short, they were giving us an opportunity to get to know each other, and the reason was not difficult to find. Harville and I being great friends, and Fanny being seventeen, it was in their minds that we might, one day, marry. But, despite her superior mind and her undoubted beauty, she awakened nothing more in me than brotherly sensations, and I am persuaded that I awakened nothing more than sisterly feelings in her. Harville was sensible enough to see it, and, as we took a turn out of doors together after dinner, he soon gave up hinting at anything between us and returned to his favourite topic of conversation, Harriet.

I let him talk, and I did not begrudge him his happiness, for we have always been the best of friends, but I am glad the visit will be over tomorrow. A man so newly engaged is not good company for anyone except the object of his affections!

Thursday 24 July

I spent the morning with Harville, Harriet and Fanny, and the three of us walked out into the country together. The sun was hot, and the ladies twirled their parasols over their heads as they went along. Harville and I teased them, saying that we had had no such shelter as we toiled under the strong sun of the Bahamas. We regaled them with tales of our water running low on board ship, saying that we often had to sail with parched throats, and by the time we returned to the house, we were all ready for a cooling drink.

I set out for Monkford late in the afternoon, leaving Harville and Harriet making plans for their wedding breakfast. The ride was enjoyable to begin with, as my way took me through varied countryside, but it was marred by a sudden downpour when I was three miles out of Monkford and I was glad to get indoors.

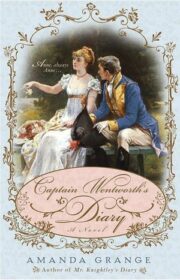

"Captain Wentworth’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.