‘I should have thought that my manner to yourself might have spared you much or all of this.’

‘No, no! your manner might be only the ease which your engagement to another man would give. I left you in this belief; and yet, I was determined to see you again. My spirits rallied with the morning, and I felt that I had still a motive for remaining here.’

We had by this time reached Camden Place, and I was forced to relinquish Anne.

‘I do not want to part from you,’ I said.

‘It is only until this evening.’

‘Ah, yes, your sister’s card party. I am surprised she invited me.’

‘You are well spoken of in Bath. She has at last, through the opinions of others, discovered your worth,’ she said.

I let her go, reluctantly, and watched her go inside, then I returned to my rooms, more happy than I had ever been.

As I dressed for the evening, I thought I might have spared myself much misery by speaking to Anne as soon as I came to Kellynch Hall.

I finished dressing and made my way to Camden Place.

The party was insipid, as all such parties are, but it gave me an opportunity to see Anne. I watched her as she moved amongst her father’s guests, glowing with happiness, and knew her happiness was for me.

I talked freely to Mr Elliot, my jealousy banished, and replaced with an excess of goodwill. I ignored the superior attitude of Lady Dalrymple and Miss Carteret, and instead I talked to them of the sea. I even exchanged pleasantries with Sir Walter and Miss Elliot. The Musgroves were there, and Harville, and we had free and easy conversation. Louisa engaged, Anne and I coming to an understanding—I had had no idea, at the start of the year, that such a happy conclusion could be reached.

I saw Anne talking to my sister and brother-in-law, and I was delighted to see how well they all got on together, for even though I had not told Sophia my news, I knew she would be pleased.

And every now and then I managed to snatch a few moments with Anne. Her shawl slipped, and I helped her with it. A fly settled in her hair, and I wafted it away, feeling the soft strands of her hair brushing my fingers.

And when I could not talk to her, I watched her.

But I could not bring myself to talk to Lady Russell. Anne noticed it, and joined me by a fine display of greenhouse plants. Pretending to admire them, so that she could speak to me without drawing watchful eyes, she asked if I had forgiven her friend.

‘Not yet, but there are hopes of her being forgiven in time,’ I said. ‘I trust to being in charity with her soon. But I too have been thinking over the past, and a question has suggested itself, whether there may not have been one person more my enemy even than that lady?’

I told her of the time, in the year eight, when I had almost written to her, but that I had been held back by fear.

‘I had been rejected once, and I did not want to take the risk of being rejected again,’ I told her, ‘but if I had then written to you, would you have answered my letter? Would you, in short, have renewed the engagement then?’

‘Would I?’ she answered, and her accent told me all.

‘Good God! you would! It is not that I did not think of it, or desire it, as what could alone crown all my other success; but I was proud, too proud to ask again. I did not understand you. I shut my eyes, and would not understand you, or do you justice. This is a recollection which ought to make me forgive everyone sooner than myself. Six years of separation and suffering might have been spared. It is a sort of pain, too, which is new to me. I have been used to the gratification of believing myself to earn every blessing that I enjoyed. I have valued myself on honourable toils and just rewards. Like other great men under reverses, I must endeavour to subdue my mind to my fortune. I must learn to brook being happier than I deserve.’

She smiled, but could do no more, for she was borne away by the Musgroves, and I had to make do with Harville’s company until the party came to an end.

Monday 27 February

I rose early and went to Camden Place where, once again, I found myself asking Sir Walter for Anne’s hand in marriage. He was a little more gracious than last time, for his friends esteem me. He expressed his surprise at my constancy and then enquired as to my fortune. On finding it to be twenty-five thousand pounds he said that it was not as large as a baronet’s daughter had a right to hope for, but declared it to be adequate. I was angered by his attitude, but I resisted the urge to say that my fortune was at least better than his, for he had nothing but debts. He gave his consent at last, then our interview was at an end.

I smiled at Anne as I returned to the drawing-room. Anne smiled back at me, and we told her sister the news. Miss Elliot showed no more warmth than formerly. She managed only a haughty look, and a slightly incredulous, ‘Indeed?’

I was angered on Anne’s behalf, for it was ungenerous of her sister not to congratulate her, but I soon saw that Anne did not care. And why should she? We had each other, so what did we care for anyone else’s approval?

‘And when will you tell Lady Russell?’ I asked Anne, as her sister left us alone.

‘Soon. This afternoon,’ she said. ‘She has a right to know, indeed, I am longing to tell her. It will be very different this time, and I hope she will be happy for me.’

‘I hope so, too, but tell her tomorrow instead. For the rest of the day, I want you to myself.’

She agreed, and we spent the time in free and frank conversation, opening our hearts to each other as we had done in the past, until it seemed that we had never been apart.

We spoke to no one, except at mealtimes, when it could not be avoided, and parted at last, reluctantly, at night.

I was longing to tell Sophia and Benjamin about my engagement, but they were away, visiting friends, and so I nursed my secret to myself.

Tuesday 28 February

I arrived at Camden Place early this morning and found that Anne was out. I waited for her, and when she returned, she told me that she had been visiting Lady Russell.

‘And how did she take the news?’ I asked Anne.

‘She struggled somewhat, but she told me that she would make an effort to become acquainted with you, and to do justice to you.’

‘Then I can ask for no more,’ I said. ‘I know she wanted to see you take your mother’s place. I cannot give you a baronetcy, but I can give you the comforts I could not provide you with eight years ago. And how has Mr Elliot taken the news? Has he heard it yet?’

‘I neither know nor care. I have just learnt that he is not the man we thought he was. We have been sadly deceived in Mr Elliot,’ she said.

I was astonished, and asked her what she meant.

‘He did not seek us out in order to repair the breach that had come between us as he claimed. Instead, he came to Bath in order to keep watch on my father. He had been warned by a friend that Mrs Clay, who accompanied my sister to Bath, had ambitions to be the next Lady Elliot.’

‘He knew that if Sir Walter married and had a son, he would lose his inheritance,’ I said, nodding thoughtfully.

‘He did. He declared that he had never spoken slightingly of the baronetcy, as my father had heard, and protested that he had always wanted to be friends. He made himself so agreeable that my father and sister were completely taken in, cordial relations were restored, and he was made welcome in Camden Place at any time.’

‘So he achieved his object of keeping a close watch on Mrs Clay.’

‘And put himself in a position to intervene if he felt it necessary.’

‘But are you sure?’ I asked.

‘I am. I learnt it from an old school friend, a Mrs Smith, who is in Bath at present. She was, once, a wealthy—comparatively wealthy—woman, and she and her husband knew Mr Elliot in London, but now she has fallen on hard times.’

I thought that this must be the same friend Mrs Lytham had told me about, and I honoured Anne for her continued friendship, even through adversity. I thought how fortunate I was to be marrying a woman who knew as well as I did that the important things in life—love, affection, friendship—had nothing to do with wealth.

‘It is largely because of Mr Elliot that my friend has suffered. He borrowed money from her husband, which he did not repay, and, even worse, he led her husband into debt. When Mr Smith died, he should have seen to it that she was able to claim some property to which she was entitled in the West Indies, for he was the executor of the will, but he ignored his duties, and as a result, my friend is living in poverty,’ she said with a sigh.

‘But this is terrible!’

‘It is indeed. If he would only bestir himself, the money raised from the property could provide her with a degree of comfort that would improve her life immeasurably.’

‘I am very sorry to hear it,’ I said. I thought for a moment, and then said, ‘I am indebted to her for opening your eyes about Mr Elliot, and I owe her my friendship because she is your friend. I have some knowledge of the West Indies, and I would be glad to help her.’

She gave me a look of heartfelt gratitude, and expressed her desire that we should go and see Mrs Smith this afternoon. This I agreed to, and when we arrived at Westgate Buildings, I was shocked to see how Anne’s friend was living. Her accommodations were limited to a noisy parlour and a dark bedroom behind. She was now an invalid, with no possibility of moving from one room to the other without assistance, and Anne told me her friend never quitted the house but to be conveyed into the warm bath.

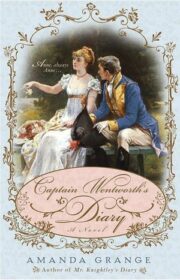

"Captain Wentworth’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.