She agreed, but said she thought it would be a happy match, for they both had good principles and good temper.

‘With all my soul I wish them happy, and rejoice over every circumstance in favour of it,’ I said, and my words were heartfelt.

But as I spoke of the Musgroves, and their true parental hearts that were anxious to promote their daughter’s comfort, I found myself gradually losing sight of Louisa and James, and thinking more of myself and Anne, for Anne had had no such parental goodwill.

I stopped as I realized where my words were tending. I glanced towards Anne and saw that her thoughts had been following mine, for she was blushing. Moreover, she had fixed her eyes on the ground and would not look at me. I remembered how it had been for us: many difficulties to contend with, opposition, caprice—everything Benwick would not have to endure.

Searching around for another subject I found I could no longer bear idle talk, I had to give her an intimation of my thoughts. I had to let her know they were unchanged, for perhaps—perhaps, if she was not irrevocably settled on Mr Elliot—she could still love me. I cleared my throat and went on, although I spoke haltingly, not sure what to say, afraid of saying too little, or too much.

‘I confess that I do think there is a disparity, too great a disparity, and in a point no less essential than mind,’ I said. ‘I regard Louisa Musgrove as a very amiable, sweet-tempered girl, and not deficient in understanding, but Benwick is something more. Had it been the effect of gratitude, had he learnt to love her because he believed her to be preferring him, it would have been another thing. But I have no reason to suppose it so. It seems, on the contrary, to have been a perfectly spontaneous, untaught feeling on his side, and this surprises me. A man like him, in his situation! With a heart pierced, wounded, almost broken! Fanny Harville was a very superior creature,’ I said, looking at Anne, and hoping to convey with my eyes that I found her a very superior creature, ‘and his attachment to her was indeed attachment.’ Again, I looked at Anne, and sought to convey that my attachment to her was indeed attachment. ‘A man does not recover from such a devotion of the heart to such a woman!’ I said. ‘He ought not; he does not,’ I finished.

If ever a man could speak of love with his eyes, I spoke of my love then. I waited breathlessly for Anne’s reply, but she said nothing. I wondered if I had gone too far, and said too much? And then I wondered if she had understood me, or if she had really thought I was speaking of Benwick, and Benwick alone. She did not seem to know what to think, or what to say.

At last she spoke.

‘I should very much like to see Lyme again.’

I was astonished.

‘Indeed! I should not have supposed that you could have found anything in Lyme to inspire such a feeling. The horror and distress you were involved in, the stretch of mind, the wear of spirits! I should have thought your last impressions of Lyme must have been strong disgust.’

‘The last few hours were certainly very painful,’ she admitted, ‘but when pain is over, the remembrance of it often becomes a pleasure. One does not love a place the less for having suffered in it, unless it has been all suffering, nothing but suffering, which was by no means the case at Lyme. We were only in anxiety and distress during the last two hours, and previously there had been a great deal of enjoyment. So much novelty and beauty! I have travelled so little, that every fresh place would be interesting to me; but there is real beauty at Lyme; and in short,’ she blushed slightly, ‘altogether my impressions of the place are very agreeable.’

I felt my emotions pulled in two directions. Were her recollections of it agreeable because of me? If so, what happiness! Or were they agreeable because of her seeing Mr Elliot for the first time there? If so, what misery!

I longed to ask, to find out, but at that moment there was a stir in the room. It had become fuller and fuller whilst I had been speaking to Anne, and it was now energized by the entrance of Lady Dalrymple. Anne moved away to greet her, and I was left alone, to wonder whether Anne’s eagerness to greet her was caused by the fact that she was attended by Mr Elliot.

They formed a happy group: Lady Dalrymple enjoyed the fawning of all about her; Sir Walter and Miss Elliot basked in the honour of her acquaintance; Mr Elliot was much taken with Anne; and Anne ... Anne seemed to welcome him. My heart ached and, unable to bear it, I left the room.

When I was at last sensible of my surroundings again, I found myself in the Concert Room. Mrs Lytham soon found me and began talking about the music that was to come. I was incapable of rational speech, but fortunately she was very fond of music, and talked enough for both of us.

‘Lady Dalrymple is here, I see,’ said Mrs Lytham.

I looked round—I could hardly help it, as Lady Dalrymple’s party entered with a bustle that was designed to catch every eye. I turned away, but not before I had seen Anne— radiant Anne, whose eyes were bright and whose cheeks were glowing with a light that came from within—sit on one of the foremost benches, next to Mr Elliot.

I took myself off to the farthest side of the room, so that I would not have to see them together, but I could not take my eyes away from her. I kept glimpsing her through the sea of feathered headdresses, her face close to Mr Elliot’s, and in the interval succeeding an Italian song, I had the mortification of seeing her speak to him in a low voice, intimately, to the exclusion of all others, with their heads almost touching.

There was a break in the performance, and I was hailed by Cranfield. He and a group of other men were discussing music and politics, and I was forced to join in. I could barely keep my mind on the conversation, however, and my gaze kept returning to Anne. She was still with Mr Elliot; still talking to him; still enjoying his company.

I heard my name, and realized that Sir Walter and Lady Dalrymple were speaking of me. I could not hear their conversation, but I imagined Sir Walter saying, Captain Wentworth once had pretensions of winning my daughter, but, as you can see, she has made a better choice, and means to marry the next baronet. He had never liked me, and he must rejoice in my total rout.

The room began to fill again in preparation for the second act, and I noticed that Mr Elliot did not return to his place by Anne. Despite my fears, I made the most of my opportunity and stepped forward with a view to sitting next to her, but others were quicker, and her bench soon filled up. I watched it; I could not help myself; and to my great good fortune, they soon tired of the music and left the room. There was a space next to Anne. I hesitated, tormented by doubt once more. Should I go to her, and discover once and forever that she regarded me as nothing more than an acquaintance from the past? Or to do nothing, and perhaps miss my opportunity with her?

I took my courage in both hands and went over to her.

‘I hope you are enjoying the concert. I expected to like it more,’ I said, thinking that, if Mr Elliot had not been present, I should certainly have been better pleased.

‘The singing is not of the first quality, it is true, but there are some fine voices, and the orchestra is good,’ she said.

I was heartened by the fact that she was disposed to talk to me, and that she did not appear to look round for Mr Elliot whilst we spoke. I was just beginning to enjoy our conversation, and was about to take my seat in the vacant space next to her, when Mr Elliot tapped her on the shoulder.

‘I beg your pardon, but your assistance is needed,’ he said to Anne. ‘Miss Carteret is very anxious to have a general idea of what is next to be sung, and she desires you to translate the Italian.’

There was something so intimate in his gesture of touching her, and something so confiding in his manner of speech, that all the joy drained out of me. I could not sit there and listen to song after song of the agonizingly beautiful music, with its romantic Italian lyrics, whilst Mr Elliot was behind us, ready to touch her shoulder again at any moment with the air of an acknowledged lover, and to bend his head close to hers, and talk to her in a low voice, their thoughts as one. I could not bear it. I knew I had to leave before the second act began, before I found myself trapped in the acutest misery. I excused myself hurriedly, saying, ‘I must wish you good night; I am going.’

‘Is not this song worth staying for?’ she asked in surprise.

‘No! there is nothing worth my staying for,’ I said bitterly.

And with this, I hurried out of the room.

I arrived back at Sophia’s house in time for supper, but I could not pay attention to her. Declaring myself exhausted, I retired to my room, where I thought of nothing but Anne and Mr Elliot, Mr Elliot and Anne.

Wednesday 22 February

I awoke to find the winter sun shining through my curtains, but the brightness, which would usually have cheered me, could not restore me to happiness, for the memory of the concert was too clearly etched on my mind.

Friday 24 February

I went out for a walk after breakfast and, to my surprise the first person I met when I set foot out of the door was Charles Musgrove! There was a start on both sides, and then a smile of recognition, which was quickly followed by a moment of awkwardness on Charles’s part. I could tell that he was thinking of Louisa, and wondering if I had been wounded by the news of her engagement. I hastened to put his mind at ease.

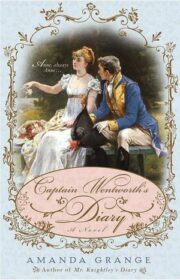

"Captain Wentworth’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.