Sir Walter looked at me as though I had confirmed all his worst suspicions about those beneath the rank of baronet, and his daughter was no more pleased. The companion started, coloured slightly, looked doubtingly at Miss Elliot, and then, with a hesitant ‘Thank you,’ took my arm.

I noticed several surprised glances from those around us as I took her onto the floor.

‘You should not have asked me to dance,’ she said mildly, as we took our places in the set. ‘We have not yet been introduced.’

‘Then why did you accept?’ I asked.

She coloured, and I thought that, although she did not have Miss Elliot’s striking beauty, she was extremely pretty, with her delicate features and dark eyes.

‘I hardly know, unless it is because I have so few opportunities to dance that I cannot afford to ignore one,’ she said.

I was about to feel sorry for her, when a spark in her eye showed me that her words, although no doubt true, were uttered with a spirit of mischief, and I found myself growing more pleased with my choice of partner.

‘You should not allow your mistress to dictate to you. Even a companion has a right to some entertainment once in a while,’ I said, as we began to dance.

Her eyes widened, then she said, ‘What makes you think I am Miss Elliot’s companion?’

‘I have not been at sea so long that I have forgotten how to detect a difference in rank,’ I said. ‘Even to my unpractised eye it is obvious. Your dress, whilst well cut, is not as elegant as Miss Elliot’s. You do not have her confidence or her air, and she speaks to you as though you are beneath her notice. Her father supports her in this, and encourages her to slight you. And then there is the fact that, as we walked onto the floor, you did not receive the deference from others that is her lot, indeed, they looked surprised to see that you had been chosen. You also have a shy and retiring disposition, suited to your role in life. But never fear,’ I went on kindly, ‘you are no doubt far more interesting than the beautiful Miss Elliot, for all she is the daughter of a baronet. And now, let us have done with Miss Elliot, I would rather talk of you. Have you lived in the neighbourhood for long?’

‘I have lived here all my life,’ she replied gravely.

‘That is a mercy. At least you have not been separated from your friends and family, in keeping with the cruel fate of most of your kind. Your mother and father are pleased to see you so well settled, I suppose?’

There was a small silence, and then she said: ‘My mother is dead.’

I cursed myself for my rough manners.

‘Forgive me. I have been a long time at sea, and I have forgotten how to behave in company. I have presumed too much on our short acquaintance, but please believe me when I say that I did not mean to distress you. Do you enjoy balls?’ I asked her, thinking that this would be a safe topic of conversation.

‘I like them very well. But you do not need to change the subject, and you must not worry that you have wounded me. My mother has been dead these five years. I miss her, but I have grown used to the pain.’

I was relieved, for I did not want to wound so delicate a creature.

‘And is your father living?’ I asked her, hoping that she was not an orphan, for then her lot in life would be hard indeed.

‘He is.’

‘That is a blessing. He is pleased to see you living at Kellynch Hall, I suppose?’ I asked.

‘Certainly. He regards it as the finest house in the neighbourhood.’

‘And he approves of the Elliots? He shares Sir Walter Elliot’s opinions and beliefs?’

‘I believe I may safely say that their thoughts coincide in every particular,’ she said.

Poor girl, I thought, if her father is another such a one as Sir Walter, but I did not say it. Instead, I asked her to tell me something of my new neighbours, in order to put her at her ease.

‘The lady to your left is Miss Scott,’ she said, indicating an elderly spinster of a timid disposition. ‘She is easily alarmed, and it is better not to speak to her about the war, for she lives in fear of the French invading England. Her sister sends her newspapers every month, telling her of some new threat, and I believe she will not rest easy until peace has been declared. Opposite is Mr Denton; he lives at Harton House. Next to him is Mrs Musgrove, and beyond her is Miss Neville.’

The dance was over all too soon. She had a surprising grace when she danced, which I found pleasing, and as a result of my attentions she had lost her downtrodden look. By the end of the dance, there was a light in her eye and some colour in her cheek, so that she was almost blooming. I escorted her to the side of the room and left her, reluctantly, with a displeased Miss Elliot, before rejoining Edward.

‘And what do you think of Miss Anne?’ he asked me.

I regarded him enquiringly.

‘Miss Anne Elliot,’ he elaborated.

‘I have not seen her. I assumed she was still at home with a chill,’ I said. ‘You must point her out to me—though if her father and sister are any indication, I do not think I wish to meet her. She will, no doubt, be proud and disagreeable, full of her own beauty and importance, and holding other people in contempt.’

‘But you have just been dancing with her!’ he said.

I was astonished.

‘What?’

I looked across the room at Miss Anne. She happened to glance round at that moment, and I caught her eye. Upon seeing me, she smiled and turned away.

‘So, that is Miss Anne!’ I exclaimed, as our conversation took on a whole new meaning. I could not help laughing. ‘I am beginning to enjoy my shore leave.’

‘I hope you are not thinking of a flirtation,’ said my brother. ‘She is very young, only nineteen, and no match for a man of your age and experience.’

‘Is she not, though? I think she is a very good match indeed. She has already given me one broadside, and I suspect she would be capable of giving me another.’

My brother looked at me doubtfully, but I clapped him on the back and told him not to worry, saying that I had no intention of harming the lady, but that a mild flirtation would help to pass the time until I return to the sea.

I am looking forward to it. I believe it will provide her with some much-needed attention, too. There is nothing like being singled out by an eligible bachelor to raise a young lady in the estimation of her friends.

Wednesday 11 June

I fell in with my brother’s idea of joining him on his duties around the village this morning, for I had nothing else to do. Whilst he pointed out the houses of every member of his congregation, and introduced me to those who were at their windows or in their gardens—which seemed to be all of them—I found myself wishing for a sight of Miss Anne Elliot. Unfortunately, the closest I came to such an encounter was when Sir Walter and Miss Elliot drove by in their carriage, going through a puddle and splashing my boots. Edward laughed, but I was not amused, for I had no servant, and when we returned to his house, I had to polish them myself.

This afternoon, after putting the shine back on my boots, I rode out into the country. I was enlivened by the sight of a milkmaid with rosy cheeks, who was carrying two pails across her shoulders by means of a yoke. I helped her to put it down as she took a drink at the well, and was rewarded with a kiss and a smile.

I was beginning to think that life in the country was very pleasant, and to understand why Edward had chosen to stay on shore, when an evening playing whist with the local worthies reminded me why I went to sea.

Friday 13 June

I rose early, full of energy, and was soon out of doors. How my brother could bear to lie in bed on such a beautiful morning I did not know. I walked through the village and then on into the country, going through fields and copses until I came to the river. I jumped it at its narrowest point, in the exuberance that comes with an early morning in summer, and went on, through verdant fields. I had just come to a small weir when a familiar figure came into view. Miss Anne Elliot was walking there, and she was coming towards me.

‘Commander Wentworth,’ she said.

There was a smile around the corners of her eyes, and it was clear she was thinking of our last encounter as much as I was.

‘I am surprised to see you here,’ I remarked as I drew level with her, determined to pay her back in her own coin, ‘for I was sure your duties as a companion would keep you inside, even on a morning as beautiful as this one. Can it be that Miss Elliot did not need you, or have you slipped out of the house whilst she is still abed? Do not neglect your obligations, I beg of you, lest you should find yourself turned out of the house. I would not like to see you made destitute for the sake of a morning’s stroll.’

She laughed up at me.

‘Are you very angry with me?’ she asked.

I smiled.

‘How could I be angry with you when you bested me in a fair fight? You would be of great value aboard a warship, Miss Elliot. Your tactics have the advantage of being both original and efficacious.’

‘It was too tempting!’ she said.

‘But what are you doing out at this hour, alone?’ I asked her. ‘I cannot believe your father would be pleased if he knew you were walking without a chaperon.’

‘On the contrary, he has no objection to my walking alone when I am on Elliot land.’

I started.

‘Yes, sir, you see, you are trespassing. The land as far as the river belongs to us.’

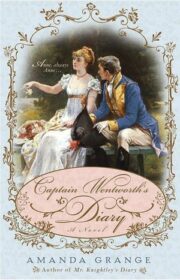

"Captain Wentworth’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.