Charles remarked that the greatcoat had been hanging over the panel, and Mary exclaimed that, if the servant had not been in mourning, she should have known him by the livery.

I, on the other hand, was vastly relieved that we had not known his identity sooner, for then introductions must have been made, and Anne would have come to know him further.

‘Putting all these very extraordinary circumstances together,’ I said, trying to hide my agitation, ‘we must consider it to be the arrangement of Providence that you should not be introduced to your cousin.’

I looked at Anne, hoping she would see it as such. To my relief, she seemed to have no wish to pursue the acquaintance, for she said that their father and Mr Elliot had not spoken for many years, and that an introduction was not desirable.

I was heartened but, without knowing her mind, I could not know her full reasons for not wanting to pursue the acquaintance. Was it because of her father, as she said, or was it ... could it be ... that her feelings were already engaged— by me?

I tried to read the answer in her face, but I could detect nothing. I wished I knew why she had refused Charles Musgrove; I wished I knew if she was indifferent to me, or whether she was merely reserved; if she had ever missed me; and if she regretted her decision to reject me.

We were soon joined by the Harvilles and Benwick, for we had arranged to take a last walk with them before departing. Harriet gave it as her opinion that her husband would have had quite enough walking by the time he reached home, and so we determined to accompany the Harvilles to their door, and then set off home ourselves.

We parted from the Harvilles as planned, and were about to return to the inn when some of the party expressed a wish to take one final walk along the Cobb. Louisa was so determined to have this last pleasure that we gave in to her, and Benwick came with us.

There was too much wind on the high part to make the walk enjoyable so we decided to go down the steps to the lower part. Louisa insisted on being jumped down them by me, as she had often been jumped down from stiles.

I tried to discourage her, saying the pavement was too hard for her feet, but she insisted. I gave in to her demands but, as I did so, I began to think that a determined character was not so very desirable after all. If it was firm in its pursuit of right, then it was estimable, but if it was firm in pursuit of its own desires, it was simply wilful.

I had done the damage, however, and must, for the time being, abide by it. I jumped her down the steps with no harm done, and there it should have ended, but she ran up the steps to be jumped down again.

Again, I tried to persuade her to abandon the idea, but I spoke in vain.

‘I am determined I will,’ she said.

She jumped with no further warning. I put out my hands; I was half a second too late; she fell on the pavement on the Lower Cobb ... and I looked at her in horror, for she was dead.

A thousand thoughts went through my mind, tormenting me for my folly: I should not have made so much of her; I should never have jumped her down from a stile; I should not have encouraged her to think that being headstrong was a virtue; I should not have brought her to Lyme. A thousand thoughts, whirling round as I caught her up, my body reacting to the crisis as it had reacted to countless crises at sea, taking charge, doing what was necessary, looking for a wound, for blood, for bruising ... but there was nothing. Yet her eyes were closed, she breathed not, and her face was like death.

‘She is dead! She is dead!’ screamed Mary, catching hold of her husband.

Henrietta fainted, and would have fallen on the steps, but for Benwick and Anne, who caught and supported her between them.

‘Is there no one to help me?’ I cried, borne down by a weight of guilt and despair, and feeling my strength gone.

‘Go to him, go to him, for heaven’s sake go to him.’

It was Anne’s voice; Anne, who could be relied upon in a crisis; Anne rousing Charles and Benwick, who were at my side in a moment, supporting Louisa. As they took her from me, I stood up, but, underestimating the effect the shock had had on me, I staggered, and once more catching sight of her pale face, I cried, ‘Oh God! her father and mother!’

I could not bear to think of them at Uppercross, imagining us happy, and trusting me to bring their daughter safely home again.

‘A surgeon!’ said Anne.

Her common sense restored me to sanity.

‘True, true, a surgeon this instant,’ I said, and I was about to go and fetch one when Anne said that Benwick would know better where one was to be found.

Again, her cool, calm common sense prevailed. Benwick gave Louisa into Charles’s care and was off for the town with the utmost rapidity.

‘Anne, what is to be done next?’ cried Charles, and I realized that everyone was looking to her in their extremity.

‘Had not she better be carried to the inn? Yes, I am sure: carry her gently to the inn,’ said Anne.

Her words roused me once again and, eager to be doing something, I took Louisa up myself. Her eyes fluttered, and I felt a moment of wild, surging hope as they opened and I knew her to be alive! What joy! What rapture!

‘She lives!’ I cried.

There was a cry of relief from all around. But then her eyes closed, and she gave no more sign of consciousness.

We had not even left the Cobb when Harville met us, for he had been alerted by Benwick on his way for the surgeon, and had run out to meet us. He told us we must avail ourselves of his house, and before long we were all beneath his roof. Louisa, under Harriet’s direction, was conveyed upstairs, and we all breathed again.

The surgeon was with us almost before it had seemed possible, and to our great relief he declared that the case was not hopeless. The head had received a severe contusion, but he had seen greater injuries recovered from.

‘Thank God!’ I said. ‘Thank God!’

My cry was echoed by her sisters and brother, and I saw Anne silently giving thanks. But my thanks were the most heartfelt of all. I had not killed her, I who had encouraged her recklessness and taught her not to listen to others. But I had injured her. It was burden enough. I sank down into a chair and slumped across the table, my head sunk on my arms, unable to forgive myself.

By and by I roused myself. I could not leave the arrangements to Anne—Anne, who had done so much, who had kept her head, and proved herself superior to all others in every way.

It was quickly arranged that Benwick would give up his room so that a member of our party could stay, giving Louisa the comfort of a familiar face in the house with her, and Harriet, an experienced nurse, took it upon herself to nurse her.

‘And Ellen, my nursery-maid, is as experienced as I am. Together we will look after her, day and night,’ she said.

I tried to thank her, but she would not take thanks, saying that she was glad to repay me for my kindness in breaking the news of Fanny’s death to Benwick. Then she returned to the upstairs room, where Anne was sitting with Louisa.

I was glad that Anne was with Louisa. It was always Anne people turned to in a time of crisis. It was Anne who had managed matters when her nephew had dislocated his collar-bone; it was Anne who had directed us when Louisa had taken a fall. Anne, always Anne who, without any fuss, showed the strength of her mind by her ability to know what was best, and to see it brought about in a quiet, calm manner. I had tried to forget her, but it had proved impossible, for she was superior to any other woman I had ever met.

‘This is a bad business,’ said Charles.

His face was white with worry.

‘My poor father and mother. How is the news to be broken to them?’ said Henrietta.

There was a silence, for no one could bear to think of it. But it must be done.

‘Musgrove, either you or I must go,’ I said.

Charles agreed, but he would not leave his sister in such a state.

‘Then I will do it,’ I said.

He thanked me heartily, and said I must take Henrietta with me, for she was overcome by the shock.

‘No, I will not leave Louisa,’ Henrietta said.

‘But think of Mama and Papa. They must have someone to comfort them when they hear the news,’ said Charles.

Her heart was touched, and she consented to go home. It was a relief to all of us, for at home she would be well taken care of, and we would not have to worry about her as well as her sister.

‘Then it is settled, Musgrove, that you stay, and that I take care of escorting your sister home,’ I said. ‘But as to the rest, your wife will, of course, wish to get back to her children; but if Anne will stay, no one so proper, so capable as Anne.’

It was at that moment that Anne appeared. Anne, collected and calm. Anne, the sight of whom filled me with strength and courage.

‘You will stay, I am sure; you will stay and nurse her,’ I said gently, longing to take her hands in mine as I had done once before, marvelling how I could fold both of them in my own. Such small hands, and yet so capable.

She coloured deeply. I wanted to speak to her, to ascertain her feelings, and to tell her mine, but now was not the time, so I made her a bow and moved away.

She turned to Charles, saying that she was happy to remain.

Everything was settled, and I hastened to the inn to hire a chaise, so that we could travel more quickly. The horses were put to, and then I had nothing to do but wait for Henrietta to join me. At last she came, but, to my surprise, Anne was with her. The reason was soon made clear to me. Being jealous of Anne, Mary had demanded to be the one to stay and help with the nursing, and had said that Anne should return to Uppercross.

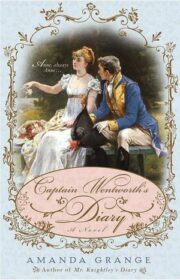

"Captain Wentworth’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.