Edward said nothing to me as we went on our way, but he looked at me, and I knew what was in his mind. Again, I had singled out Miss Anne, and again given her my wholehearted attention.

‘How long will you be away for Harville’s wedding?’ he asked me.

‘I go tomorrow, and will be back on Wednesday night.’

He seemed satisfied, for he knew as well as I did that it meant I could not talk to Miss Anne before Thursday.

Tuesday 19 August

I set out early, at a leisurely pace, blessing my horse, who made light work of the hills along the way. I arrived to find Harville in a nervous state, for though he welcomed me warmly, his conversation was punctuated by bouts of high spirits and equally frequent bouts of reflection.

‘You are not regretting it?’ I asked him.

He looked surprised, and I was reassured, for he could not cry off, even if he wanted to.

‘Not at all,’ he said. ‘I am looking forward to it. Only, I am conscious of the fact that, after tomorrow, my life will never be the same again. It has made me unsettled. I cannot see the future—but I dare say it will become routine soon enough. I am surprised you do not follow my example and marry, Wentworth. A bachelor’s life is a dry existence. You should find a good woman, someone you can love and esteem, someone to think about when you are away at sea, and someone to come home to when you are on shore leave.’

‘Not I!’ I replied, though not as heartily as I would have done a month go. ‘I am far too young for such a step, and I have too much of the world still to see. And as for shore leave, I can stay with my brother when I am home.’

‘Not as comfortable as staying with a wife,’ he said.

‘That is true, but a brother is not as hard to leave behind.’

His family were gathered about him, looking forward to the celebration. Benwick and Jenson were there, too, and I thought how quickly the time had gone since we had all met at the naval academy.

‘It is about time you made an honest woman of Harriet,’ said Harville’s brother, laughing at him. ‘You have been sighing over her for long enough!’

‘It is a grave responsibility,’ said his cousin, shaking his head.

‘You speak as though Harville was going to be burdened with command of the Navy, instead of being given the duties of a husband to one pretty woman,’ said Benwick.

‘At least I have my friends to defend me!’ said Harville.

But his peace was short lived. The rest of his family joined in and he was subjected to as many opinions on marriage as there were men in the room.

At last he cried, ‘Enough!’ and begged us all to talk of something else.

But as I retired for the night, I could not put his words from my mind. Follow my example and marry, Wentworth.

At last, feeling restless and knowing I would be unable to sleep, I slipped out of the house. It was a beautiful night, with a balmy breeze, and I made my way by moonlight along the road. As I did so, I thought of how I had felt, a few months ago, when Harville had told me he intended to marry. I had been incredulous, thinking him a fool, for the world was full of pretty young women, and why should he want to swap the smiles of so many for the smiles of one?

But as I stood at the crossroads, I understood.

Wednesday 20 August

Harville was up very early, and full of nerves. He found it impossible to tie his neck-cloth and I had to do it for him. Then he could not get into his coat, and Benwick and I had to assist him. He could not settle to anything, and although we tried to talk to him about his next ship, and his certainty of capturing more prizes as soon as he went back to sea, he did not listen to more than one word in ten.

It was far too early to go to the church, but he insisted we set out, with the result that we waited fifteen minutes at the altar. I thought he would wear his hands away with all the clasping and unclasping he did!

At last Harriet arrived, looking radiant in a satin gown. The service began, and as I watched Harville make his vows, I found that I no longer pitied him. I envied him.

As we emerged from the church, Harriet’s mother was crying, and Harville’s mother and sister were crying, but Harriet was beaming with joy.

We went back to Harriet’s house for the wedding-breakfast. After we had all eaten and drunk our fill, toasted the happy couple and made our speeches, the Harvilles set out on their wedding-tour.

Jenson, Benwick and I lingered on, enjoying the hospitality of Harville’s family. Benwick seemed very taken with Fanny, whilst Jenson talked to Harville’s parents and I spent the afternoon talking to Harville’s brother. We relived our battles and looked forward to the battles to come, hoping we might, at some time in the future, find ourselves on the same ship.

And then, at last, it was time for me to leave. I bade them all farewell, and thanked them for their kindness. They sent me off with their good wishes ringing in my ears, and I rode home at a steady pace. The weather remained fine, and I was treated to a magnificent sunset on the way. I reined in my horse and watched the spectacle, seeing the sky turn crimson before the sun sank below the horizon. Then I set off again, arriving shortly after dark. Edward was reading the newspaper, but as I entered the room he laid it aside and asked me how I had got on. I told him all my news and he asked me a number of questions about the service. I satisfied him as best I could, and he allowed it to have been well done.

Then he told me his own news, which was not so happy, for the curacy of Leigh Ings had been given elsewhere.

‘Never mind, there is still the living of Trewithing,’ I reminded him.

‘There is, and it would suit me better to have a living, rather than another curacy. I must hope for better luck there.’

‘Do you think it will fall to you?’ I asked.

‘Nothing is certain,’ he said, ‘but as I have friends in the neighbourhood, and as I do not think there is any particular interest in the living, I think it possible.’

‘It would be a very good thing if it did.’

‘Undoubtedly. I would have my own parish, a larger house, an increased stipend, and I would be better placed to hear of any other livings that might fall vacant.’

‘The church is not an easy profession for a man with no one to speak for him, unlike the Navy, where a man may prove his worth,’ I remarked.

‘But it is still not impossible to rise in the world,’ he said.

‘With Sophia well married, and I a commander, I would like to see you become a bishop,’ I said.

He only laughed, and said he did not have my ambition. Nevertheless, he expressed his intention of walking into town tomorrow in an effort to learn more.

We said our goodnights.

As I mounted the stairs, my thoughts returned to Harville, now married, and realized that a part of my life had changed. He and I had been as brothers, but now he had moved on to a new life, and I felt a restlessness inside me, a longing to move on to a new life of my own.

Thursday 21 August

Edward walked into town this afternoon to learn all he could about the living at Trewithing. Whilst he was out, a note was delivered from Kellynch Hall, and I had to contain my impatience until he returned, for it was addressed to him.

‘Upon my soul!’ he exclaimed as he opened it. ‘We are invited to dine with Sir Walter Elliot at Kellynch Hall.’

‘There must be some mistake,’ I said.

‘See for yourself.’

He threw the note to me. Sure enough, it was an invitation.

‘I thought Sir Walter did not like me,’ I said in surprise.

‘My dear brother, not every invitation that arrives is a compliment to you. It is possible that he wishes to see me. If he has heard of my hopes—but no, he would be no more interested in the rector of a small parish than he is in the curate of an even smaller one. He is simply being neighbourly, that is all.’

‘Either that, or he needs to make up his numbers.’

‘You are not a very trusting man, Frederick.’

‘I have found it better to err on the side of caution when going into battle,’ I replied.

‘Sir Walter is surely no match for a man of your abilities,’ he mocked me.

No, I thought, but Lady Russell is.

I could not help wondering if she was behind the invitation. Did she want to see me, so that she might have an opportunity of getting to know me, and of observing my behaviour towards Miss Anne at close quarters? Did she, perhaps, think that a commander might not be a bad husband for her favourite, after all? Or did she want an opportunity to warn me away?

Friday 29 August

‘You seem to have dressed with unusual care,’ remarked Edward as I joined him in his sitting-room, prior to our setting out for Kellynch Hall.

‘Not at all. I am always carefully of my appearance,’ I said, adding, ‘as long as it does not involve wearing veils.’

The weather being fine, we decided to walk to Kellynch Hall. When we arrived, I had my first full sight of it, for although I had glimpsed it when walking by the river, I had never seen it from the front. As we walked up the drive, I thought it a very fine house, and said so to my brother.

‘Something similar would suit me when I have made my fortune,’ I said.

‘I do not doubt it, but you have to make your fortune first,’ he returned.

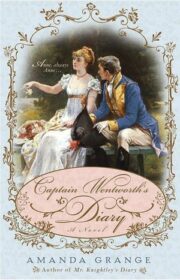

"Captain Wentworth’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Captain Wentworth’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.