‘My arms ache from carrying those buckets of powder all day.’

‘Well, a lot of girls are doing the same thing, my girl, it’s war work, it’s that or the forces, or farm work, at least this way you sleep at home safe and sound.’

Her mother poured her a cup of tea from the cherry-coloured teapot; it was strong and hot and Kate drank it, grateful for the kind gesture rather than the tea itself, somehow tea didn’t taste the same these days.

‘One of your friends called for you, that Jenny, the one you used to work with at RTB, she wants you to meet her at the ice cream parlour but sure, if I were you, I’d go straight to my bed after supper, you look all in.’

‘I’ll see how I feel later.’ Kate wondered if she could summon the energy to go out tonight and yet anything was better than sitting in all evening listening to her mammy go on about the war and how in her day it was all different, in the first war the men were men and they showed the Hun that the British were not to be ruled by anyone.

As her mother filled the bowls with soup and cut great doorsteps of bread Kate heard the door bang open. ‘Paul’s home.’ The warning was unnecessary as her growing brother barged into the kitchen. Mammy had brought him home as soon as the blitz on Swansea had eased a bit. Mammy needed her brood around her she said.

‘Jesus, Mary and Joseph, take your time Paulie!’ Kate shook her head. ‘You’re like a homing pigeon—you know fine enough when the food is on the table.’

He scrambled on to a chair and frowned under his thick fringe of hair when his mother told him to go and wash his hands.

‘That girl wants to see you, the one you used to work with, said you’re going out with her, she’s coming for you about eight o clock.’ Mrs Houlihan pushed a bowl of soup Paul’s way and over her shoulder spoke to Kate.

‘You look tired but perhaps it would do you good to get out a bit, you been stuck in here for days and I’m tired of you under my feet.’

So that was decided then, she would go out. In a way Kate was glad to have the decision taken out of her hands.

‘Soup’s lovely, Mammy.’ She spoke between mouthfuls, preventing her mother from making any further comments. She’d wear her grey dress and her red shoes and that lovely red scarf Eddie had given her. Tears came to her eyes at the thought of sweet, darling Eddie but she ate doggedly and willed the tears away.

Later, arm in arm with Jenny, Kate tottered through the town towards Mario’s Ice Cream Parlour. Inside the huge blackout curtains, the room was bright, heavy with smoke. A couple of lads leaned over a table in the corner looking the girls over, much to Jenny’s delight. She preened and slid one leg over the other revealing a shapely knee.

Kate sat head down, not wanting to be seen. Stephen was among the gang of young men. She’d ‘been’ with him, let him into her drawers, he was probably telling the others about it now just like he told Eddie; they were leering and laughing raucously punching each other’s arms in the way that men did when they were excited.

Kate tried to talk to Jenny but they’d never had much in common and all Jenny seemed to want her for was company while she found herself some man to keep her happy.

To Kate’s horror Jenny invited the men to join them and they came hotfoot across the floor, pushing chairs into place between the girls. Stephen was beside Kate and put his hand in a proprietary way on her knee. She quietly removed it.

‘Don’t go all innocent on me now, Kate, you were willing enough that night outside the church, practically on a poor fool’s grave. Right juicy you were, too, a bit of all right, what boys? He pinched one of her full breasts, it hurt and instinctively she slapped his hand away.

‘You brazen bitch! Hot one minute and then all saintly, eh? What did I have then I don’t have now?’

‘You had fear,’ she said gently, ‘you were terrified, you begged for me to love you, you told me you were afraid of going to war.’

‘Huh! As if I would be so unmanly.’ He was scarlet.

Kate picked up her coat. ‘And most of all you had tears, you cried in my arms like a baby. I did what I could to help you. Good night, Stephen, and good luck.’

She walked out into the dark night and made her way towards home, glad of the evening breeze on her cheeks. She’d only gone as far as the middle of town when the air-raid siren scorched her ears. She stood still for a moment, frozen with fear.

Bombers droned overhead, searchlights raked the sky. She saw them descend, the beautiful deathly candles of light, and then she began to run to the cover of the nearest shelter and cowered inside, huddled against other frightened people drawn close by the twin feelings of anger and fear for what was happening to them and to their beloved Swansea.

Eleven

Hari looked up as Colonel Edwards stopped at her desk. He smiled down at her, a lined man big and bluff who had served valorously in the war of 1914–18. He walked with a stick now but she’d found that his brain was strong and active, and his eyes gleamed with intelligence.

He sat opposite her, his injured leg jutting out awkwardly before him. ‘You like your work Miss Jones, you have no desire to join the armed forces?’

She looked at him in surprise. I think I’m happy to serve my country in any way I’m needed, sir.’ She wondered if it was a rebuke.

‘So you are happy to do your war work here in Bridgend?’

‘Yes, very.’

‘Good, that’s what I wanted to hear. ‘You are quick to learn, articulate and clever. You are a well-educated young lady I understand?’

‘I did well at my school.’

‘No need of false humility,’ he said almost abruptly. ‘As you already know, the work you do is secret, I don’t want to be mysterious but signals are passed all over the country, bomber pilot to bomber pilot, among other things. Most reach Bletchley Park but it’s also my job to pick them up and decipher them, yours too if you have an aptitude for it.’

He handed her a page of writing. ‘It’s given to some intelligent civilians like you to do this work. Now this is the fairly easy code I use, it’s a peculiar shorthand of my own. I make notes of what comes my way, it’s all above board, government work, you understand? In the event of systems failing somewhere along the line, at least we here have some of the, possibly vital, pieces of information.’

Hari wondered what he was getting at. He read her mind. ‘As I said, I want to teach you to share my job. Anything could happen to me; I’m getting older and slower. Two heads, I feel, are better than one and your head is a young eager one.’

Hari was doubtful. ‘I’m honoured at your confidence, sir, but am I up to this sort of work?’

‘Well, before we go on to the difficult work,’ he said, smiling, ‘I want you to do a spot of work on this machine here. It’s a new listening radio I bought, or rather the government bought it. It’s almost like a regular wireless but you listen out for Morse messages. You understand Morse, don’t you? Learned it in girl guides like most other kiddies I expect.’

Hari nodded doubtfully. ‘Only the basics, sir.’

‘Well, you’ll soon get the hang of it. We’ve found that some of the German operators get careless and make it easier for us to work out the message.’

‘You think I’ll be any good at this sir?’

He stood up, ignoring her question. ‘The messages will be in Morse but they will be coded, as I said. Just play with the damn thing, I’ll come back and see you later.’

Oh, there’s a kettle over there on the stove and tea stuff. You can’t get up and go for lunch if there’s an important message coming through, you understand?’

‘Yes sir.’

He left her then and Hari began to panic. However much she tried to concentrate, she could make little sense of the machine. Life had been easier handling simple calls in the bigger office. She couldn’t do this, she just didn’t have the ability. She rubbed her eyes and then stared at the piece of paper the colonel had given her. She would just have to try her best, but first she would make herself a much-needed cup of tea.

Hari persevered throughout the day not even stopping to eat the sandwiches she’d brought with her. She drank a lot of tea and stared at the strange codes until at last they began to make something resembling sense.

The radio buzzed into life and Hari panicked. She listened to the tapping sounds that rose and fell as if coming from a distance. She hastily scribbled the letters represented by the long and short signals; she would try to work out their pattern later.

‘How are you doing, Miss Jones?’ Colonel Edwards’ voice startled her. She looked up and put her arms over the papers she was attempting to work on and then realized how foolish she must seem. This man, this intelligent man, was well used to deciphering messages from the wireless.

He smiled. ‘Well done, I see you’ll be discretion itself. Now, how are you getting along?’

‘I don’t think I’m getting very far, sir,’ she said, ‘though some of the words are beginning to make sense.’

‘Anything important come through?’

She was taken aback. ‘I don’t know, sir. I’m sorry, I wasn’t taking notes I was so busy trying to understand how it works.’

He held up his hand. ‘No problem, just keep trying. I’ll give you a few lessons tomorrow. Go home now, I don’t want you to miss your bus to the station.’

Hari felt weariness drape over her like a fog; going home on the bus, then on to the train, darkness pressed against the windows, drowning her. She closed her eyes for a moment. Kate sitting beside her, touched her arm. ‘You all right?’

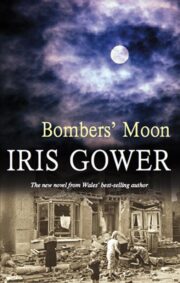

"Bombers’ Moon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bombers’ Moon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bombers’ Moon" друзьям в соцсетях.