I went to bed early and lay awake thinking of the biscuit tin in my drawer at the office and I knew I would have to find somewhere to hide it before the SS began looking at my life too closely.

Forty-Seven

Stephen took Kate’s hand as she felt her way through the gate of the park. ‘Come and sit down,’ he said gently.

They had sat there together before in very different circumstances. ‘I’m well Stephen,’ she said. ‘There’s no need to worry about me.’

‘And the baby?’

Kate was a long time answering. Her baby, their baby, had been born two weeks ago, a small, weakly boy.

‘Kate?’

‘He’s not very well.’

‘I must come to see him.’

‘But Eddie.’

‘Damn Eddie!’ He gripped her hand tightly. ‘I’m the father, Kate, I have a right to see my little son.’

Kate hung her head. He was right of course and Eddie should understand, being a father himself. ‘All right.’

‘Come on, I’ll take you in the car.’ Stephen put a hand under her elbow and urged her to her feet.

‘We’ll walk,’ Kate said firmly, ‘the last thing I want is the neighbours talking about your big posh car stopping outside our house.’

It was a fine autumn day and Hilda had just hung sheets on the line in the back garden. Kate could hear the snap of the sheets in the wind. ‘Adam has been sick again,’ she said.

Kate’s heart sank. The baby, born three weeks too early, had been sickly from the start. ‘I hoped he was growing out of that by now.’ Kate was weary, there was so much to think about, to worry about, and now Stephen was making demands, complicating matters even more for her.

‘Can I pick him up?’ Kate heard him move the covers from Adam’s crib.

‘Carefully then,’ she said, ‘we don’t want him to be sick again, do we?’ The chair creaked and Kate knew that Stephen had seated himself with the little baby in his arms. Suddenly Kate felt very ill. She leaned back against her chair and tried not to think.

The door opened and she could smell the scent of her husband. She heard the pause as Eddie took in the scene.

‘Eddie.’ She tried to stand but then she was falling, falling into a deep well and, thankfully, she let herself fall.

She was in bed, in hospital. She recognized the sounds from when she’d been in before. The rustle of starched aprons, the slap, slap of soft-soled shoes on the floor and the all-pervading, unmistakable smell of cleaning fluid.

‘What’s wrong with me?’ Her voice was thin, weak.

‘It’s all right, dear.’ A cool hand touched her forehead. ‘You’ve had an operation, that’s all. You’re going to be just fine.’

‘An operation—what sort of operation?’

‘You’ve had a hysterectomy. Your abdomen had split open, scars broken down—there were complications—but you’ve come through it very well, you’ll be fit again in a few weeks.’ The hand was removed, the sound of feet dying away, and Kate struggled to come to terms with what she’d been told.

There had been a danger all along that her old scars would open when the baby was born but that hadn’t happened. Why now?

She heard footsteps approaching once more. Her arm was lifted and a sharp prick of a needle pierced her arm.

‘There, rest now, have a good sleep and when you wake your loved ones will be here to see you.’

‘Loved ones… am I going to die then?’

‘There was no answer, the nurse had gone away and Kate was left alone to wonder if she would live to rear her firstborn and her poor, sickly Adam.

Forty-Eight

Hari drew up outside the farmhouse and Jessie appeared in the doorway, her brow furrowed but a hopeful smile on her face.

‘Any news, Hari?’ Her tone was eager. ‘Come in, cariad, come in and sit down.’ Hari sat in the living room, which was a mess. Dust had built up like clouds on the furniture and Jessie was looking gaunt and old. She coughed incessantly.

‘I’ve heard from Meryl in a roundabout sort of way,’ Hari said. ‘A message over air waves, a bit of Welsh, my name.’ She could say nothing more; the rest of the message was secret and might not even be correct.

‘And Michael?’

‘I don’t know.’ Hari’s voice was low with misery. ‘I assume he’s alive or Meryl would have found a way to let me know. But, and it’s a big but, he’s either in prison or on active service for the Germans.’

Jessie sighed heavily. ‘His father would have influence. I’m sure he’ll look after Michael. I’ll make us a cup of tea.’

Jessie’s answer to every crisis was a cup of tea. She was very affected by her son’s disappearance, her footsteps faltering as she made her way to the kitchen.

Hari followed her. The kitchen was in a terrible state and Hari took off her coat and washed the accumulation of dishes. Jessie made a faint protest but there was a look of relief on her face as Hari brushed up the debris on the kitchen floor.

Hari was silent for a long time but as she put away the brush she looked at Jessie.

‘I need your help,’ she said.

Jessie’s face brightened. ‘Anything girl, you’ve been so good to me since… well, you know.’

‘I want you to come and stay for a few weeks,’ she said. ‘Father is home for a break, he’ll be all alone while I’m at work and he’s not very good on his one leg.’

It wasn’t true; her father was well able to look after himself. Jessie obviously wasn’t, not just now.

‘Leave the farm? Oh, I don’t know, Hari, what about the cattle?’

‘I’m sure the man on the next farm would take them in, there’s so few of them now, anyway.’ She touched Jessie’s arm. ‘It would only be for a short while, in any case, and I do need your help, really I do.’

‘When?’ Jessie asked.

‘Father’s coming home Monday, what if I come for you next Sunday, would that suit you?’

‘Duw, I suppose so. It’s only for a while though, mind.’

‘I know.’ Hari smiled with relief. ‘I’ll expect a nice cooked meal for Father and me when I come home from the factory, though.’

‘So long as we put our rations together it will be all right. Could I bring a few chucks with me for eggs?’

‘We could manage chickens in the garden, I suppose,’ Hari said. ‘Just so long as you don’t bring a pig for bacon as well.’

Hari had the satisfaction of knowing the house looked tidier when she left and Jessie was busy washing clothes to bring to Swansea with her. A spell with company might just be what Jessie needed; she was all alone in that deserted farmhouse, alone and afraid.

As she drove along the farm road towards the main thoroughfare for Swansea, a figure suddenly stepped out in front of her car. She pulled up and saw George Dixon wave his arms at her frantically.

‘Help me, miss—it’s my mother, she’s taken really bad. I don’t know what to do; I don’t know how long she’s been sick. I’ve just come home on leave, see?’

George was in army uniform, he was a junior officer, commissioned no less. Mrs Dixon must be well connected. ‘Get in.’

Hari drove to the Dixon Farm and hurried across the yard into the house. Mrs Dixon was in bed; it was clear she had a fever. Her face was flushed, almost cyanosed, her eyes were puffy and she had strange red marks on her skin.

‘I’ve called the doctor,’ George said. ‘I ran to the post office in the village and used their phone but so far there’s no sign of anyone coming.’

‘She is very ill.’ Hari looked at her watch. ‘If the doctor doesn’t come soon we’ll take her to the hospital.’

As she finished speaking the doctor came plodding up the stairs. He was very old with a white moustache and a shock of white hair under his hat.

‘Doctor Merriman.’ He nodded briefly to Hari and went straight to the bed. After a moment he shook his head. ‘I’m too late,’ he said. ‘Mrs Dixon is dying, she’s had scarlet fever for at least a week. I’m sorry.’

‘How long?’ George’s voice was hoarse.

‘You’ll be lucky, son, if she lasts the night. I’ll give her something to ease her and then all you can do is sit with her, talk to her gently, help her slip away peacefully. I’m sorry.’ He repeated helplessly, ‘It’s just too late to help her.’

‘If only I’d been here,’ George said angrily. ‘This bastard war.’ He put his head in his hands and wept.

Forty-Nine

I became accustomed to the routine of going to work on the radio section in the big, sprawling building that stood out like a landmark on the flat countryside near Hamburg. I became so used to speaking German that sometimes, even in my thoughts, I used German words.

The girls around me became my firm friends, especially the flirtatious Eva, a fluffy blonde girl with a beautiful face and a clinical, clever brain. Even Frau Hoffman had warmed enough to smile occasionally. As one of the girls remarked, ‘She must be in love.’

And yet sometimes, feeling absurdly like a traitor to Germany, I would take my box of ‘sanitary products’ with me into the fields as far away from my home and my workplace as my bike would take me and send any potentially useful pieces of information back, I hoped, to Hari in Bridgend.

The winter of 1944 was long, spring seemed determined not to come. I spent my evenings mostly alone in the farmhouse, practising codes on pieces of paper.

One night, I was almost sleeping in my chair with the fire dying in the hearth when I heard the sound of a car outside. I sat up; it must be Herr Euler, who sometimes made a call home at odd times. I wondered if it was to check up on me but so far he’d caught me doing no more than reading or writing endless letters to Michael that he probably seldom received.

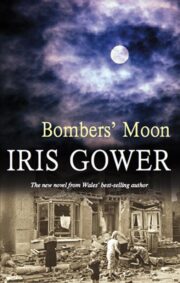

"Bombers’ Moon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bombers’ Moon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bombers’ Moon" друзьям в соцсетях.