Hari stumbled out into the night and sagged against the railings fronting the lodge. She had a sister and a father and neither of them were there for her when she needed them. Hari slid to the ground and began to cry. Around her the tang of autumn sharpened the air, the leaves, gold and bronze in the sun, looked sullen and dull in the evening light.

Overhead, the clouds cleared. Through the chill air came the faint drone of planes. The sound intensified, filling the world. Hari ran instinctively for shelter. Bullets hailed down as though searching for her. They spat on the ground at her heels. She dived for the sparse cover of the bushes on the outskirts of the lodge and threw herself flat, the smell of earth in her nostrils and the tears she was still shedding sinking into the ground.

Was that Michael up there in one of the bombers? Would he fly over Carmarthen as well as Swansea and bomb the farm and even his mother into oblivion?

And then the lodge itself took a direct hit. The walls were gone, huge chunks of masonry flew like massive missives towards her. One whole wall landed within inches of where she lay; flames shot into the darkening sky, licking at the night, illuminating the surrounding area.

Hari stayed on the ground feeling leaves crackle against her cheeks as she turned her head to look at the devastation that was occurring all around her. The bombers, their targets lit and exposed by the flames from the old hospital buildings, dropped more bombs, easily hitting the surrounding houses. The whole world seemed to be in flames. Hell had come for her before she was even dead.

Eventually, the bombers droned away, their task complete. Hari sat up and looked at the still-burning lodge, the funeral pyre for all those inside. Hari cried for Colonel Edwards but was glad that he had died before suffering the indignity of being blown to death by the Luftwaffe.

Eventually, she staggered to her feet and looked into the basin of Swansea Bay. A ship that was waiting for the incoming tide was on fire. Flares of flames like bonfires showed where houses had been hit. Tiny figures ran about the devastated streets like ants. She waved her fists to the sky in a useless gesture of anger.

Hari began to walk down the hill, making her way back to the town. If she was lucky her house would still be standing and she would lie in her own bed and sleep all the pain away.

As she rounded the corner she saw her house was there, solid and welcoming and she closed the door on the carnage outside with a sigh of resignation and relief.

The talk at Bridgend the next day revolved around Colonel Edwards. Hari was asked many times how he had died. She told them briefly. ‘He passed away peacefully before the bombing.’ And silently she thanked God it was true.

She went to her radio at last but there was nothing coming through. She sat with her head in her hands until, at last, she heard the tap of the machine.

The message was being passed on from Bletchley Park; she could tell it was passed on by Babs. After the official code and brief, precise message, the tapping became faltering, the sender clearly inexperienced. Hari took down the coded message with difficulty, the transmission was intermittent and then unbelievably she recognized some words not in code but in Welsh. Her own name, Angharad, the word for darling, cariad, and ‘it’s me, sis. Black Opal.’ And the radio went dead.

Forty-Six

The next day I went out into the fields and tried to figure out the radio, wishing there was a book of instructions with it, but of course any official spy would have been properly trained on its use. I had finally worked out that the big dial was the frequency finder. God knows how I had managed to send a message at all I was so ignorant. All I could hope was that someone, hopefully not the Germans, would have picked it up. I didn’t know how useful the information would be and, in any case, perhaps some real spy had sent the message using the transceiver properly.

I had to hide the case again so I closed it securely and wrapped it in a stiff cotton pillowcase and an old mackintosh, so big it must be Herr Euler’s, and then carried the radio out further into the field and dug a pit. I went back to the farmhouse then to cook myself some lunch.

I had the usual eggs and bread and, luxury, a bit of chicken, and sat outside to eat my meal in the quiet of the countryside. I wished Jessie was here to cook with her usual efficiency and chatter at the same time. I was lonely. But tomorrow I would be back at work, among my colleagues, my friends, if I was to be truthful. Friends and enemies—how do you distinguish them?

The silence was suddenly broken by the sound of cars driving up outside the farmhouse. I got up wondering, with a beating heart, if Michael was home.

The man who stepped out of the car was a stranger; he stood there shoulders hunched to break down any resistance and stared at me suspiciously.

‘I am Frau Euler,’ I said, ‘what are you doing here if I may ask?’ It paid to be polite to big hard men in SS uniform.

‘I am Von Kestle. I have to search your house. Anyone else here?’

I shook my head. ‘My husband is in the skies somewhere bombing the enemy.’ I hoped that he was dropping his bombs in the sea. ‘And my father-in-law Herr Euler is no doubt busy working for the fatherland in his office in Hamburg.’

The man paused, taken aback, and then he clicked his heels. ‘Forgive the intrusion Frau Euler,’ he said quickly, ‘but we have reports of enemy activity in the area, we have to search.’

‘There was a spy here some time ago but Herr Euler got rid of her,’ I said quickly.

‘They work together these traitors,’ the man said sternly. ‘There is usually a nest of them—like vipers. Now, I’d like to come inside, Frau Euler.’

I stepped back hurriedly and waved my arm. ‘Please come in, you are welcome to search my house if only for my own safety. Can I fetch you any refreshments?’

‘Nein! Danke.’

I moved away and sat at the kitchen table. I didn’t have to try to look afraid. I was nearly wetting my knickers as I’d done when I was a thirteen-year-old girl being evacuated to the country. What a lot had happened to me since those days when all I had to fight was the bullying of Georgie Porgy Dixon.

I knew the case was not in the house but it was not very well hidden either. I had been too careless; I would have to make better arrangements in the future—if I was allowed any future. I knew I would be arrested or even shot if I could be tied in somehow to the radio set.

Eventually the men went outside and searched the chicken coup and the broken-down barn. I heard them swish at the bushes with their guns and cringed with fear until they went away defeated with just a salute in my direction.

I would have to go further away to send any more signals as I couldn’t risk being anywhere near the farmhouse again. I hadn’t thought they could track the signal so easily.

I sat shivering for most of the evening trying to work out the safest way to get messages home should I need to. The difficult thing would be finding the correct frequency. I knew from the time I’d spent in Hari’s office that it was changed every day.

Anyway, there was no news to send at the moment, nothing that was of any importance. When there was, then I’d tackle the problem.

I dug up the case early in the morning and fitted the parts into a large biscuit tin. Then I made a bonfire of the paperwork from inside the case, poor Rhiannon wouldn’t need it now. I wrapped the case in newspaper and hid it under a pile of horse manure.

A shopping bag tied to the handles of my bike hid the tin. I’d taped paper to the lid and printed ‘Sanitary Goods’ on the lid. I couldn’t think of anything else to do.

The next morning, I took the shopping bag into the building where I worked. The security man took a brief look inside and, embarrassed at the writing on the tin, handed the bag back to me. I hung up my coat and stuffed my scarf into my pocket. It all looked very innocent.

I put the tin in my desk drawer for now; later, I would find a cupboard where I could hide it. In the event that the radio was found, I couldn’t be blamed any more than anyone else in the building.

I worked hard through the day and listened for anything out of the ordinary to come through my earphones. I sent the usual signals, giving information to airmen or the navy vessels off shore at Antwerp. Mundane tasks that made up my day.

When I arrived home at the farmhouse, there were cars everywhere and men in uniform digging in the shrubbery. I caught sight of Von Kestle and he came towards me, his huge booted feet covering the ground swiftly.

‘We have found evidence of the ground being tampered with,’ he said. ‘Somebody was there, digging.’

I put my hand to my mouth. ‘Oh my God!’

‘You know nothing of this?’

‘How could I? I have been at work in my Hamburg office all day,’ I said.

‘The signal that was picked up twenty-four hours ago was from here, on this farm.’

‘I told you,’ I said. ‘Herr Euler found a woman here, a spy, he dealt with her. Whatever she left behind has got nothing to do with the Euler family, I give you my word on it.’

After a moment the man nodded. ‘I understand. But we will have to keep observing this area, just in case.’

I wasn’t sure he believed me but without evidence there was nothing he could do. The soldiers went away and I drank some tea, telling myself I wasn’t cut out to be a spy. I didn’t like taking risks but there were certain things that had to be done for the sake of my country.

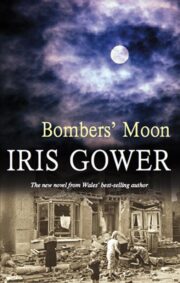

"Bombers’ Moon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bombers’ Moon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bombers’ Moon" друзьям в соцсетях.