And then she had a phone call; it was from Colonel Edwards. ‘You’d better come home, I’ve heard from your sister. Don’t worry, everything is well, but come home at once.’

Was this his way of bringing her back to Swansea or did he really have intelligence about Meryl? Her trembling nerves got the better of her and she covered her face with her hands. And was there any news about Michael?

Forty

Kate sat in the doctor’s waiting room hands folded in her lap. Everything was fine, the baby, Stephen’s baby, was growing normally and the scars looked as if they would hold for another birth. If not, the doctor said, Kate could have the child by Caesarean section.

She heard the door open and lifted her head. Hilda had come to fetch her. She heard Teddy snuffle, he had a cold and he started snivelling when he saw Kate and bumped against her legs. She held him, took out her handkerchief and by some instinct found his nose.

They went outside. ‘Everything’s fine,’ Kate said, afraid to voice her real thoughts that she wished the baby would slip away. It was such a betrayal carrying Stephen’s baby in her womb when her real love had come home to her.

‘Teddy’s caught Eddie’s cold,’ Hilda said unnecessarily. ‘Eddie’s gone to bed, sent in a sick note to work, he’ll be laid up for at least a week. You know what babies men are.’

Kate felt Hilda stiffen at her side.

‘Hello, Kate.’ It was Stephen, his voice was kind, concerned, there was pain underlying every word. Kate tried to smile. She held out her hand and Stephen took it.

‘The doctor said the baby is fine.’ She hoped she sounded reassuring. ‘I’m fine too. There could be trouble with my scars but if there is they’ll operate, nothing to worry about.’

Stephen coughed as though to hide his feelings. ‘Can I give you a lift home?’

‘You’ve got a car, you must be doing well,’ Kate said.

‘Now I’m no longer able to fly I’m no great use to the force. I’ve set up a new business but I can tell you about that another time, let me give you a lift home, the rain is getting heavy.’

Kate was going to refuse but Teddy began to cry.

‘Car,’ he said, ‘I want to go in car.’

‘All right,’ Kate said humbly and let Stephen hand her into a soft back seat. Huffing and puffing, Hilda sat beside her with Teddy on her lap.

‘It’s very kind of you I’m sure.’ Her tone was not cordial. ‘Perhaps you’d like a cup of tea or something when we get back?’

Kate knew what the invitation had cost Hilda. She liked Stephen, was grateful to him, even, for supporting them all the time Eddie was away, but now her son had returned and she had every mother’s protective instincts where her own were concerned.

‘I would very much like to—’ Stephen must have caught Kate’s tiny shake of the head—‘but I’m afraid I’m busy today.’

He drove on in silence and Kate felt like a traitor. She had married in haste, for the best reason in the world—to give her son a decent future—but now she was paying a terrible price.

Stephen left them at the door and, for a moment, Kate touched his hand. ‘Thank you for your kindness,’ she said softly. ‘I’ll keep in touch about the baby, I promise.’

She heard him sigh. ‘I was so happy there, for a while, Kate… you, and my baby on the way—what more could a man want?’

‘I’m sorry, Stephen, I do love you, in a way, but Eddie is my…’

‘Don’t say any more—’ Stephen’s voice was suddenly harsh—‘I don’t think I can bear to hear it. Look after yourself and my child, that’s all I ask of you.’

Kate felt her way into the house and the warmth of the kitchen reached out to her. She could smell tea, hear it being poured into cups. She sank down into a chair and burst into tears.

Hilda held her. ‘There, there, life’s been hard on you girl but remember one thing, you have a lot of people who love you, that’s worth more than gold any day.’

What Hilda said was right but why then did Kate feel such a desperate pain, finding it so hard to come to terms with the awful situation she was in? Two men, two children; such tangled lives. She sighed. Why was she worrying, tomorrow they could all be dead.

Forty-One

I was at home in the German farmhouse alone. I had a week’s leave from the radio control room and I was glad to be out from under Frau Hoffman’s beady eye for a few days. Her last words to me as I left were: ‘When do you intend to provide some fine sons to fight for the fatherland?’

‘As soon as you do.’ I knew at once it was unwise of me to say that. Frau Hoffman’s face darkened and she stared at me with her cold eyes that would freeze a sea over, if there had been a sea anywhere near us.

She raised her hand and slapped my face hard and I had to bite my lip and apologize. ‘I am sorry, Frau Hoffman, that was rude of me.’

‘Go!’

I went. Now I was alone in the farmhouse wondering why I could not stop my sharp answers even now when I was in such a precarious position.

I looked out into the yard and saw the few chickens stalking about as if they owned the world. They must be German chickens, I giggled to myself. And then I thought of Michael, my love—how could I be against the race that had reared my darling man? Michael would be home on leave in a few days and my heart did a flip of joy.

‘Duw,’ I said to myself, ‘I’m turning into a silly, soft woman, what in heaven’s name is wrong with me?’

I looked again at the chickens; if I wanted to eat I would have to kill one of them. I shuddered. I’d reluctantly plucked chickens, cut them into pieces, but it had been Jessie who’d actually done the killing on the farm in Carmarthen.

On the other hand I’d brought bread and cheese from one of the small shops near Hamburg; I could always make do. I stared out at the hens again and took a deep breath. I would have to do it sooner or later. Now, while I was alone, might be the best time. If I made a fool of myself I would be the only one to see it.

The hens took no notice of me as I tiptoed near them a sharp knife hidden up my sleeve. I picked out one hen, black-feathered, dainty claw raised like a dancer. ‘Sorry dear,’ I said in German, ‘it is your turn to die for your country.’

The damn thing understood me and started to run for its life. The other hens scattered, wary of me. They must have a language of their own and the obstructive black hen had warned them what I was about.

I chased the creature into the clump of bushes at the edge of the field and fell on it. The hen wriggled and clucked and I lifted its beak and thrust the knife in deep into its throat. Now I had to hang it up to drain it of blood. That’s what I’d seen Jessie do. She’d had the niceties of a shed and a bucket I had to make do with a branch of a tree and the bare earth.

The poor thing gave a strangled cough and dropped its head as though giving up. I stood back and was violently sick. I heard a soft thud from the other side of the bushes and I jumped as though the wrath of God had fallen on me. I was trembling.

After a moment, I peered through the bushes and saw a woman lying on the ground, a silk parachute tangled like a bridal dress around her.

I stood dazed, staring at her. At her side was a little brown case, her weekend undies I thought hysterically.

She started to mumble and I crept nearer. Her eyes were closed but her lips were moving. ‘Iesu Grist beth sydd wedi digwydd?’

Incredibly she was speaking Welsh. I knelt beside her and smoothed her forehead. Whatever hat she’d been wearing had been torn away, there were ties around her neck. ‘What are you doing in Germany saying “Jesus Christ” and asking what’s happened, in Welsh?’

She opened her eyes and stared at me and then, fearfully, looked round. She saw the dead chicken hanging from the tree dripping blood and tried to edge away from me. ‘Look—’ I still spoke in Welsh—‘I’m from Swansea, it’s all right I’m not going to hurt you. Can you stand? I’ll help you back to the farmhouse.’

‘The parachute, the case…’ She broke off uncertain how far to trust me.

‘I’ll hide them.’ I stuffed the silk tangle of the chute into the bracken and hid the case a little way off in some soft ground. It was heavy and my heart quickened as I guessed it was just what I needed: a radio.

‘Barod?’ I asked, ‘ready?’

She was unhurt and after a moment she walked steadily at my side. A tall woman, strong-shouldered but with a sweet face and curling dark hair. She was silent as I let us both into the farmhouse, looking around as though she still didn’t trust me. I didn’t blame her. I’d be suspicious too of a woman who lived in a German farmhouse.

We drank some brandy, we both needed it and, gradually, she began to relax.

‘Do you live here alone?’ It was asked casually but it was really important to her safety, we both knew that.

‘At the moment.’

‘Go on.’ She spoke in English now and was very well spoken, cultured, well educated. Probably from a rich family, a spy, well trained and trying to interrogate me.

‘Nothing to go on about.’

‘Why are you here?’

‘Why are you here is more to the point.’

‘Sharp aren’t you?’

‘I have to be,’ I said. ‘I’m living in Germany.’

‘I want to know…’

‘What you want to know is irrelevant, I have nothing to say, I have no need to explain anything to you. Just be glad it was I who found you. We’ll eat now.’

It was too late to start on the chicken and I didn’t have the heart. I went out to get some eggs and the woman followed me, still suspicious.

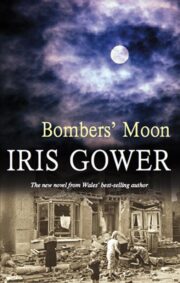

"Bombers’ Moon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bombers’ Moon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bombers’ Moon" друзьям в соцсетях.