‘How was I to know he was alive?’ Kate’s hands were held out imploringly. ‘I needed my son, Eddie’s son, to be born in marriage. I sure didn’t want him being called a bastard, you know that Hilda—’ her hand touched Hari’s—‘and so do you my dear, dear friend.’

‘No one’s blaming you.’ Hari’s voice was soft.

‘Too right no one is blaming her,’ Hilda agreed.

‘Eddie is and so is Stephen come to that. How in the name of God and all the angels could I have made such a mess of my life? I had two fine men to love me and now I’ve lost both of them.’

‘Which one do you really want, that’s the question,’ Hilda said sharply.

‘I want my Eddie,’ Kate said simply.

A voice from the doorway was full of love and gladness. ‘It’s me, Kate, Eddie. I’ve come back home and what you’ve just said, that’s exactly what I needed to know.’

They clung together, weeping, and Hari left them and walked the empty, silent streets towards her home.

Thirty-Six

I looked at the strange land of Germany and felt alien and frightened. I had to remind myself that Michael was born here, lived here until he was ten before Jessie took him home to Wales.

The German officer had managed to contact Herr Euler and eventually believed our story and let us go once we reached the coast of Saint-Nazaire. We had been dropped ashore and we needed to head through Germany, making for the farmlands North of Hamburg. There, his father would no doubt arrange for papers for us both; our excuse for not identifying ourselves was good—all our possessions had been lost at sea.

I grew up then, all at once. I looked at Michael and knew without doubt he could never love me; it was a dream of mine, a hopeless, helpless dream. He talked incessantly about my sister; he talked about Hari’s amazing hair, her beauty, her warmth of spirit. The trouble was I agreed with him; Hari was all those things. I loved her and I hated her.

An army lorry drove by us filled with uniformed soldiers. They stopped with a screech of brakes and sharp words, most of which I understood, shot like bullets at Michael. He replied quickly, explained our situation, mentioned the submarine commander and his father and then, magically, we were gestured to board over the back and into the well of the truck.

Michael talked about his father and one of the officers frowned. ‘Euler?’ he said, and Michael nodded. After that, the men became respectful but distant. I had the impression they knew of Michael’s father and feared him. I must have fallen asleep against Michael’s shoulder then because when I opened my eyes we were in farmland, flat with not a hill or a mountain in sight, not at all like Jessie’s place in Carmarthen.

I heard the familiar, mournful sounds of the herds and the fussy, gossipy cluck of hens as they scratched with sharp claws at the ground. If I closed my eyes again, I could be back in Carmarthen. I wished I was.

Michael helped me down on to the road and thanked the driver of the truck. ‘You don’t talk much,’ the man said to me in English. I looked at him blankly. He wasn’t going to catch me that easily.

Michael took my arm and set off across a field, straddling the rows of green weed things that showed the crop was potato, perhaps turnips. I never did learn a lot about the land.

Back home with Jessie I knew less about plucking a chicken and cooking it, so how we were to survive on the German farm was a mystery. I’d spent my nights at home learning German with Michael. Lovely times, they were, sitting at the fireside listening to the radio or to the coals shifting in the fireplace.

The farmhouse came into sight. ‘Home.’ Michael spoke in German and I looked at him sharply. ‘This isn’t home,’ I said, ‘are you forgetting Jessie and Carmarthen already? Are you turning into a German!’

He was silent. I never ever knew what Michael was really thinking.

The house was built of stone, mellow and yellow in the fading light and criss-crossed with wood, something like the old Elizabethan houses at home. The windows appeared blank like eyes that couldn’t see and I found I was shivering.

Herr Euler was waiting for us. He was a tall man with a moustache, a soldier in uniform. There was a familiarity about him, and then I realized there was a strong resemblance between father and son.

‘Michael?’ His tone was questioning, he peered closer. ‘Mein Gott! Come inside, boy.’ His strong guttural German was hard to understand. He hardly looked at me, miserable old sod.

‘I’m Meryl,’ I said in German. He looked down at me from his great height. He didn’t reply.

‘Michael, what are you doing here in Germany, come to fight a just cause at last have you, boy?’

The room had no lights. Michael ushered me towards the fire and the flames from the logs threw shadows of us into corners and on to floors and walls—everything was strangely unreal.

I must have dozed while Michael told his father the story of what we’d been through but I was awake enough to know it was carefully edited.

‘And who is this woman?’ Herr Euler’s tone was hostile as though I was a camp follower or something.

‘I’m Michael’s future wife,’ I said quickly. I had the feeling that if Herr Euler thought any different I would be tossed out on my ear. ‘We lost everything in the shipwreck, we’ve no papers or anything.’

‘Why did you bring her?’ His father’s tone was abrupt.

Michael shrugged. ‘It’s a long story. Can you help us get papers?’

‘First, food.’ And then he did something that I thought must be out of character for him so awkward was he: he hugged Michael and patted his back. ‘It’s good to see you back in the Fatherland, my son.’

Michael’s eyes were misty and I felt a pang of unease. Would he be a turncoat now he was back in Germany?

We ate chicken and potatoes and then we all went to bed. I was muddle-headed and worried but I was too tired to stay awake. I cuddled myself with my arms, used now to sleeping alongside Michael’s warmth. He had never treated me as anything other than a sister but nevertheless we’d been side by side curled together, a pair. I shivered and Michael hugged me, just for comfort. I knew that was all he had to offer me.

Herr Euler was very clever and next morning he set the wheels in motion for acquiring papers for both Michael and me. He chose a church in the small village nearby for our marriage by a proper German clergyman, and by some miracle Michael and I really were man and wife. But, only in name, I warned myself. As soon as we got back home, if ever we did, I knew the marriage would be annulled.

We had no wedding breakfast, just a drink of some German stuff and a slice of bread and cheese, but I had a ring on my finger and my papers would carry the name Frau Euler.

My short-lived euphoria disappeared when Michael’s father warned us that matters were desperate and even younger boys than Michael were being called to serve their country. ‘You will have to join the forces.’ He spoke sternly and Michael glanced at me before nodding.

A few days later, Herr Euler had a sheet of paper in his hand when I got up for breakfast. The fire was still not lit and there was no sign of food. Michael came into the room from the backyard, his hair was wet and glistening with diamond drops of water.

‘My leave is over,’ Herr Euler said. ‘You were lucky that you came when you did otherwise you’d have been in deep trouble.’ I didn’t catch everything he said but I got the gist of it and I was suddenly frightened. He had offered us security, got us a legitimate identity, papers we could show anyone who cared to examine our presence in the country.

Now he was leaving us alone and though Michael was courageous, inventive and adaptable, he was unfamiliar with the working of Germany, of this Hitler who ruled everyone and stuck his arm up in the air and shouted like a buffoon.

‘Thanks for being so kind,’ I said, in German. Herr Euler nearly smiled.

‘Your German’s not bad, not bad at all,’ he said. ‘I have something for you; it was my mother’s. As Michael’s wife, it should be yours.’ He handed me a ring. ‘It’s a black opal,’ he said. ‘Very rare.’ I glanced at Michael; he looked sour but what was I to do? I took the ring and slipped it on my finger. It glimmered with colour and I was fascinated.

We heard a car outside. Herr Euler clipped his heels together, shook hands with Michael, nodded to me and left us. The engine outside revved as the truck drew away.

‘What now?’ I said anxiously.

‘We get a message to Jessie and to Hari. Can you do it, Meryl?’

‘If I can find a radio I can use.’ My mouth was dry, he hadn’t forgotten about home then.

‘I’ll find you what I can. There should be some bits and pieces around my father’s house, he always did like to tweak the radio.’ He smiled. ‘You and he would have a lot in common.’ From the little I had learned about radios the task of making one would be much more difficult than Michael realized but I kept my own counsel about that.

We settled down to a sort of routine; we would search for pieces of electrical stuff, anything I could use to make a signal. In the evenings when it was too dark to work, we sat near the fire and talked, really talked, and I knew Michael was more mine then than he had ever been. If only he would love me as a man loved a woman. But it might happen, I really hoped it might happen given time. A week later Michael was called up.

Thirty-Seven

Hari drew up at the door of the farmhouse tired and blurry-eyed; she’d driven all the way from Buckinghamshire. Jessie was waiting at the door, wiping her hands in her apron. Her face was lined and anxious. Hari felt overwhelmed with hopelessness, it was obvious Jessie had heard nothing from Michael.

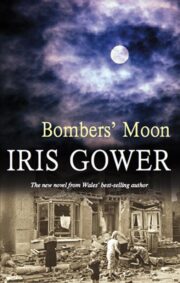

"Bombers’ Moon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bombers’ Moon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bombers’ Moon" друзьям в соцсетях.