Abby now made the discovery that it was possible, at one and the same time, to be furiously angry, and to have the greatest difficulty in suppressing an almost irresistible desire to burst out laughing. After a severe struggle, she managed to say: “This—this is useless, sir! Let me assure you that you have no hope whatever of gaining the consent of Fanny’s guardian to your proposal; and let me also tell you that she will not come into possession of her inheritance until she is five-and-twenty! That, I collect, is something you were not aware of!”

“No,” he admitted. “I wasn’t!”

“Until that date,” Abby continued, “her fortune is under the sole control of her guardian, and he, I must tell you, will not, under any circumstances, relinquish that control into the hands of her husband one moment before her twenty-fifth birthday, if she marries without his consent and approval. I think it doubtful, even, that he would continue to allow her to receive any part of the income accruing from her fortune. Not a very good bargain, sir, do you think?”

“It seems to be a very bad one. Who, by the way, is Fanny’s guardian?”

“Her uncle, of course! Surely she must have told you so?” replied Abby impatiently.

“Well, no!” he said, still more apologetically. “She really had no opportunity to do so!”

“Had no—Mr Calverleigh, are you asking me to believe that you—you embarked on this attempt to recover your own fortune without first discovering what were the exact terms of her father’s will? That is coming it very much too strong!”

“Who was her father?” he interrupted, regarding her from under suddenly frowning brows. “You talk of her inheritance—You don’t mean to tell me she’s Rowland Wendover’s daughter?”

“Yes—if it should be necessary for me to do so—which I strongly doubt!” said Abby, eyeing him with hostility. “She is an orphan, and the ward of my brother James.”

“Poor girl!” He studied her appraisingly. “So you are a sister of Rowland Wendover! You know, I find that very hard to believe.”

“Indeed! It is nevertheless true—though in what way it concerns the point at issue—”

“Oh, it doesn’t!” he said, smiling disarmingly at her. “Now I come to think of it, he had several sisters, hadn’t he? I expect you must be the youngest of them. He was older than I was, and you are a mere child. By the by, when did he die?”

This question, put to her in a tone of casual interest, seemed to her to be so inapposite that the suspicion that he was drunk occurred to her. He showed none of the recognizable signs of inebriation, but she knew that her experience was limited. If he was not drunk, the only other explanation of his quite fantastic behaviour must be that he was slightly deranged. Unless he was trying, in some obscure fashion, to set her at a disadvantage? She found it impossible to understand what he hoped to gain by his extraordinary tactics, but the look of amusement on his face made her feel, uneasily, that he had an end in view: probably an unscrupulous end. Watching him closely, she said: “My brother died twelve years ago. I am his youngest sister, but you are mistaken in thinking me a mere child.I daresay you wish I were!”

“No, I don’t. Why should I?” he asked, mildly surprised.

“Because you might find it easier to flummery me!”

“But I don’t want to flummery you!”

“Just as well!” she retorted. “You wouldn’t succeed! I am more than eight-and-twenty, Mr Calverleigh!”

“Well, that seems like a child to me. How much more?” She was by now extremely angry, but for the second time she was obliged to choke back an involuntary giggle. She said unsteadily: “Talking to you is like—like talking to an eel!’

“No, is it? I’ve never tried to talk to an eel. Isn’t it a waste of time?

She choked. “Not such a waste of time as talking to you!”

“You’re surely not going to tell me that eels find you more entertaining than I do?” he said incredulously.

That was rather too much for her: she did giggle, and was furious with herself for having done so. “That’s better!” he said approvingly.

She recovered herself. “Let me ask you one question, sir! IfI seem like a child to you, in what light do you regard a girl of seventeen?”

“Oh, as a member of the infantry!”

This careless reply made her gasp. Her eyes flashed; she demanded: “How old do you think my niece is, pray?”

“Never having met your niece, I haven’t a notion!”

“Never having—But—Good God, then you cannot be Mr Calverleigh! But when I asked you, you said you were!”

“Of course I did! Tell me, is there a nephew of mine at large in Bath?”

“Nephew? A—a Mr Stacy Calverleigh!”

“Yes, that’s it. I’m his Uncle Miles.”

“Oh!” she uttered, staring at him in the liveliest astonishment.

“You can’t mean that you are the one who—” She broke off in some confusion, and added hurriedly: “The one who went to India!”

He laughed. “Yes, I’m the black sheep of the family!” She blushed, but said: “I wasn’t going to say that!”

“Weren’t you? Why not? You won’t hurt my feelings!”

“I wouldn’t be so uncivil! And if it comes to black sheep—!”

“Once you become entangled with Calverleighs, it’s bound to,” he said. “We came to England with the Conqueror, you know. It’s my belief that our ancestor was one of the thatchgallows he brought with him. There were any number of ‘em in his train.”

A delicious gurgle of laughter broke from her. “Oh, no, were there? I didn’t know—but I never heard anyone claim a thatch-gallows for his ancestor!”

“No, I don’t suppose you did. I never met any of us came-over-with-the-Conquest fellows who wouldn’t hold to it, buckle and thong, that his ancestor was a Norman baron. Just as likely to have been one of the scaff and raff of Europe. I wish you will sit down!”

At this point, Abby knew that it behoved her to take polite leave of Mr Miles Calverleigh. She sat down, offering her conscience a sop in the form of a hope that Mr Miles Calverleigh might be of assistance to her in circumventing the designs of his nephew. She chose one of the straight-backed chairs ranged round the table, and watched him dispose his long limbs in another, at right-angles to her. His attitude was as negligent as his conversation, for he crossed his legs, dug one hand into his pocket, and laid his other arm along the table. He seemed to have very little regard for the conventions governing polite conduct, and Abby, in whom the conventions were deeply inculcated, was far less shocked than amused. Her expressive eyes twinkled engagingly as she said: “May I speak frankly to you, sir? About your nephew? I do not wish to offend you, but I fancy he is more the black sheep of your family than you are!”

“Oh, I shouldn’t think so at all!” he responded. “He sounds more like a cawker to me, if he’s making up to a girl who won’t come into her inheritance for eight years!”

“I have every reason to think,” said Abby frostily, “that my niece is not the first heiress he has—as you phrase it!—made up to!”

“Well, if he’s hanging out for a rich wife, I don’t suppose she is.”

Her fingers tightened round the handle of her parasol. “Mr Calverleigh, I have not yet met your nephew. He came to Bath while I was away, visiting my sisters, and was called to London, on matters of business, I am told, before I returned. My hope is that he has realized that his—his suit is hopeless, and won’t come back, but your presence in Bath quite dashes that hope, since I collect you must have come here in the expectation of seeing him.”

“Oh, no!” he assured her. “Whatever put that notion into your head?”

She blinked. “I assumed—well, naturally I assumed that you had come in search of him! I mean,—so close a relative, and, I understand, the only member of your immediate family still living—?”

“What of it? You know, fiddle-faddle about families and close relatives is so much humbug! I haven’t seen that nephew of mine since he was a grubby brat—if I saw him then, which very likely I didn’t, for I never went near my brother if I could avoid it—so why the devil should I want to see him now?”

She could think of no answer to this, but it seemed to her so ruthless that she wondered, remembering that he had been packed off to India in disgrace, whether it arose from feelings of rancour. However, his next words, which were uttered in a thoughtful tone, and quite dispassionately, lent no colour to her suspicion. He said: “You know, there’s a great deal of balderdash talked about family affection. How much affection have you for your family?”

Such a question had never before been put to her; and, since it was one of the accepted tenets that one loved and respected one’s parents, and (at the least) loved one’s brothers and sisters, she had not previously considered the matter. But just as she was about to assure this outrageous person that she was devoted to every member of her family the unendearing images rose before her mind’s eye of her father, of her two brothers, and even of her sister Jane. She said, a little ruefully: “For my mother, and for two of my sisters, a great deal.”

“Ah, I never had any sisters, and my mother died when I was a schoolboy.”

“You are much to be pitied,” she said.

“Oh, no, I don’t think so!” he replied. “I don’t like obligations.” The disarming smile crept back into his eyes, as they rested on her face. “My family disowned me more than twenty years ago, you know!”

“Yes, I did know. That is—I have been told that they did,” she said. She added, with the flicker of a shy smile: “I think it was a dreadful thing to have done, and—and perhaps is the reason why you don’t wish to meet your nephew?”

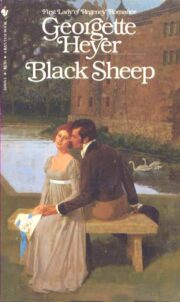

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.