It had not occurred to him that he might meet with a refusal, nor did her response to his proposal alarm him.

“Marry you?” said Mrs Clapham, laughing. “Me? Good gracious no!”

He took this for coyness, and was rather impatient of it, but he said, in his most caressing voice: “I think it was your sportive playfulness which made me tumble headlong in love with you. And I had believed myself to be case-hardened!”

Her next words were disturbing. “Well, by what I’m told, you weren’t so case-hardened but what you were making up to that pretty little girl who bowed to you in Cheap Street, before I came to Bath!”

It was the manner in which she spoke which disturbed him more than her words. There had always been a danger that she might discover how particularly he had attached himself to Fanny, and he knew just how to deal with that. He was unprepared for the change in her voice, and in her demeanour, and it startled him. He had hitherto supposed her to be a silly, fluttering little ingenue,but she was not looking at all ingenuous, and her voice was not only decidedly tart, but it had lost some of its gentility. It disconcerted him, but only momentarily: he realized that she was suspicious of a rival, and jealous of her. He laughed, flinging up his hands. “What, little Fanny Wendover? Oh, Nancy, Nancy, you absurd and adorable witch! My dear, do you know how old she is? Seventeen! Not out of school yet!”

“More shame to you!” she said.

“Yes, indeed, if I had made up to her. Oh, these Bath quizzies! I warned you how it would be! But I own I did not think that at my age I should be suspected of dangling after a mere child only because I took notice of her, and indulged her with a little very mild flirtation!”

He trod over to her chair, and dropped gracefully on to his knee, and possessed himself of her hands, smiling up into her face. “I have had many flirts, but never a true love till now!” he said whimsically.

“Well, you haven’t got one in me!” said Mrs Clapham. “I’ve had many flirts too, but I’ve no wish for a husband, so you may as well stop making a cake of yourself! Going down on your knees, as if you was playing Romeo!”

“I know how unworthy of you I am, but I dared to hope you were not indifferent to me!” he persevered.

“Get up, do!” responded the lady unromantically, pulling her hands away.

He obeyed her, looking remarkably foolish, and shaken quite off his balance. He stammered: “How is this? It cannot be that you have been trifling with me! I cannot believe you could be so heartless!”

“Oh, can’t you?” she retorted, getting up, and shaking out her skirt. “Now, you listen to me, Mr Flat-catching Calverleigh! It don’t become you to talk of hearts, and it isn’t a particle of use pitching me any more of your gammon, because I’m up to all the rigs! We’ve had an agreeable flirtation, and the best thing you can do now is to own yourself beaten at your own game, and take yourself off! Otherwise you might hear a few things you wouldn’t relish. Taking notice of a school-girl! Cutting a sham with an heiress is what you were doing, and not for the first time, I’ll be bound! Well, I don’t want to say anything unladylike, but,”she ended, overcoming this reluctance, “you’re one as would marry a midden for muck, and that’s the truth!”

He was white with mingled shock and rage. He opened his mouth to speak, but shut it again, for there was nothing he could say. He turned, and walked out of the room.

His was not a sensitive nature. He could shrug off a snub; he could listen with indifference to the strictures of Mr James Wendover. But Mr Wendover’s contempt had been expressed with icy propriety. No one had ever torn his character to shreds with the crude vulgarity favoured by Mrs Clapham, and it was some time before he could in any way recover from his fury. It was not the truth of what she had said that provoked this fury: it was her incredible insolence in daring to address him—a Calverleigh!—in such terms.

When his rage abated, it was succeeded by fear, a more deadly fear than he had ever before experienced, for it was unattended by even a glimmer of optimism. There was no way left to him of staving off his creditors; he would be forced to pawn his few pieces of jewellery to enable him to pay his shot at the White Hart, and to buy himself a seat on the stage-coach to London. He tried to think of someone from whom he might be able to borrow a hundred pounds, or even fifty pounds, but there was no one—certainly no one in Bath.

He had reached the point of entertaining wild thoughts of abandoning his luggage, and escaping from the White Hart with his bill unpaid, when he was interrupted by the entrance of one of the waiters, who presented him with a letter, which had been brought, he said, by one of the servants employed at the York House Hotel.

Stacy did not recognize the careless scrawl, but when he spread open the single sheet he found that it was from his uncle, and briefly invited him to dine at York House that evening.

His first impulse was to send back a refusal. Then it occurred to him that he might be able to induce Miles to lend him some money, even if it was only a pony. He must be fairly flush in the pocket, he thought, for although he bore none of the signs of being well-inlaid he was again putting up at the most expensive hotel in Bath, which he could not have done had he left his shot unpaid when he went off to London so suddenly. He bade the waiter stay a moment while he wrote a reply to his uncle’s letter, and was considerably provoked when he learned that the messenger had departed, having been told that no answer was expected. Coupled with the curt nature of the invitation, which might well have been mistaken for a command, this amounted to an affront, and set up Stacy’s bristles. He decided to overlook it: his uncle’s manners were deplorably casual, and probably he had had no intention of offending.

Upon arrival at York House, he was taken to Miles Calverleigh’s sitting-room, where the table had already been laid for dinner. Determined to please, he exerted himself to be an affable, conversable, and even deferential guest. He praised the excellence of the dishes set before him; he said that it was not often that he was offered burgundy of such rare quality; he recounted such items of Bath-news as might be supposed to be of interest; he tried to draw Miles out on the subject of India. Miles regarded him with an amused eye, contributed little to the conversation, butt outdid him in affability.

When the cloth had been removed, and the brandy placed on the table, Stacy said, with his air of rueful frankness: “I must tell you, sir, that I was devilish glad to get your letter! I’ve been drawing the bustle a trifle too freely, and find myself on the rocks. Only temporarily, of course, but I’ve no banking accommodation in Bath, which puts me in a stupid fix. I don’t like to ask it of you but I should be very grateful if you could lend me a trifle—just to keep me in pitch and pay over an awkward period, you know!”

His uncle removed the stopper from the decanter in his leisurely way, and poured brandy into the glasses. “No, I won’t lend you money,” he said.

He spoke with his usual amiability, but there was something in his voice which Stacy had never heard before. It was almost an implacable note, he thought. Surprised, and slightly nettled, he said: “Good God, sir, I don’t want any considerable sum!”

Miles shook his head. Without quite knowing why, Stacy felt a stir of alarm in his breast. He forced up a laugh. “If you must have it, sir, it’s damned low water with me—until I can bring myself about! I haven’t sixpence to scratch with!”

“I know you haven’t.”

The placidity with which this was uttered made Stacy flame into anger. He jumped up, his hands clenching and unclenching.

“Do you indeed? Well, let me tell you, my very dear uncle, that unless I can be given time to find some means of raising the recruits there will be a writ of forfeiture served on me!”

“Oh, it needn’t come to that!”

“Needn’t come to it? Are you quite blubber-headed? Don’t you—”

Miles laughed. “No, no, I’m not at all blubber-headed!”

“I beg pardon!” Stacy said, choking down his rage. “I didn’t mean to say that! The thing is—”

“No need to apologize,” said Miles kindly. “No need to tell me what the thing is either.”

“I am afraid, sir,” said Stacy, trying to speak politely, “that owing, no doubt, to your long residence abroad you are not familiar with the—the various conditions attached to mortgages. I must explain to you—”

“You are in arrears with the interest, and you have no possible means of paying up. Sit down!” He picked up his glass, and sipped some of the brandy in it. “That’s why I sent for you.”

“Sent for me?” interrupted Stacy.

“Did I say sent for you? It must have been a slip of the tongue. Begged for the honour of your company!”

“I cannot imagine why,” muttered Stacy resentfully.

“Just on a matter of business. I want two things from you: one is an equity of redemption; the other is Danescourt—by which is to be understood the house, and the small amount of unencumbered land on which it stands. For these I am prepared to forgo the interest owing on the existent mortgages, and to pay you fifteen thousand pounds.”

Stacy was so thunderstruck by these calmly spoken words that his brained whirled. He almost doubted whether he had heard his uncle aright, for what he had said was entirely fantastic. Feeling dazed and incredulous, he watched Miles stroll over to the fire, and take a spill from a jar on the mantelpiece. He found his voice, but only to stammer: “B-but—equity of redemption—why, that means—Damn you, is this your notion of a joke?”

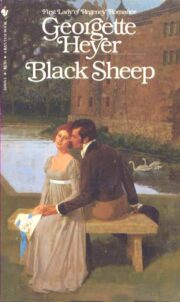

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.