The eldest Miss Wendover’s devoted handmaid fixed her with an eye of doom, and delivered herself of a surprising statement “I feel it to be my duty to tell you, Miss Abby, that I don’t like the look of Miss Selina—not at all I don’t!”

“Oh!” said Abby weakly. “Is—is she feeling poorly? I will come up to her.”

“Yes, miss. I was never one to make a mountain out of a molehill, as the saying is,” stated Fardle inaccurately, “but it gave me quite a turn when I went to dress Miss Selina not ten minutes ago. It is not for me to say what knocked her up, Miss Abby, and I hope I know my duty better than to tell you that it’s my belief it was Mr James that burnt her to the socket. All I know is that no sooner had he left the house than she went up to her room, saying she was going to rest on her bed, which was only to be expected. But when I went up to her she wasn’t on her bed, nor hadn’t been, as you will see for yourself, miss. And hardly a word did she speak, except to say she wouldn’t be going down to dinner, and didn’t want a tray sent up to her. Which is not like her, Miss Abby, and can’t but make one fear that she’s going into a Decline.”

On this heartening suggestion, she ushered Abby into Selina’s room. Kindly but firmly shutting the door upon her, Abby looked across the room at her sister, who was seated motionless beside the fire, with a shawl huddled round her shoulders, and a look in her face which Abby had never seen there before.

“Selina! Dearest!” she said, going quickly forward, to drop on her knees, gathering Selina’s hands into her own. Selina’s eyes turned towards her in a stunned gaze which alarmed Abby far more than a flood of tears would have done. “I have been thinking,” she said. “Thinking, and thinking ... It was my fault. If I hadn’t invited her to our party she wouldn’t have written such things to Cornelia.”

“Nonsense, dearest!” Abby said, gently chafing her hands. “Now, you know you promised me you wouldn’t say another word about That Woman!”

She had hoped to have coaxed a smile out of Selina, but after staring at her uncomprehendingly Selina uttered: “It was because I was cross! That was why you said you would marry him, wasn’t it? But I didn’t mean it, Abby, I didn’t mean it!”

“Goose cap! I know you didn’t!”

Selina’s thin fingers closed round her own like claws. “James said—But I told him it was no such thing! He put you all on end, didn’t he? I guessed how it must have been. I told him. I said that there was no question of—I said you would never dream of marrying Mr Calverleigh. And you wouldn’t, would you, Abby?”

Meeting Selina’s strained, searching eyes, Abby hesitated, before saying: “My dear, why put yourself into such a taking? I thought you wished me to marry?”

“Not Mr Calverleigh! I never wished it, except for your sake, but I thought, if you married Mr Dunston—so kind—in every way so suitable—and everyone would have been pleased, and you wouldn’t have gone away from me, not quite away from me, because I might have seen you every day—”

“Selina, I shall never go quite away from you,” Abby said quietly. “This is the merest agitation of nerves! You have let James talk you into high fidgets. In spite of his top-boots, and his careless ways, you don’t dislike Mr Calverleigh. Why, it was you who first said how unjust it was to condemn him for the sins of his youth!”

“But I didn’t know that you meant to marry him,” said Selina simply.

“Well, nor did I, at that time. Come, my dear, there is no occasion for this despair!”

But by the time Selina, still clutching her hand, had enumerated the ills which would result from such a marriage there seemed to be every reason for despair. The list was a long one, and it ranged over a wide ground, which included the mortification which would be suffered by the family at the marriage of one of its members to a black sheep; the sneers of Mrs Ruscombe; the impossibility of Selina’s remaining in Bath, where she was so well known; the harm that would be done to Fanny, on the verge of her come-out; of Fanny’s unhappiness at being separated from her dearest aunt; of her own misery at being estranged from James, and Jane, and perhaps even Mary.

At this point, Abby was moved to expostulate: “But you wouldn’t be, stoopid!”

“James warned me. He left me in such anger! Because I told him that I should never give you up, whatever you did, which I never, never would! And he said that if I supported you I should cut myself off from the family—so dreadful, Abby!—so that I should do well to consider carefully before I made my choice, only there is no choice, so what a silly thing to say, and how could he suppose I would choose anyone but you, if there were? And as for not looking to see his face again, I said that if he was unkind to you he need not look to see my face, which is true, only I can’t bear to think of it, because we have always been so happy, and even if we don’t very often see the others they are our family!”

Abby was so much touched by this unexpected championship that tears started to her eyes. “Oh, my dearest! How brave of you—how loyal! Do you indeed love me so much?”

“But of course I do!” said Selina.

Abby kissed her. “Best of my sisters!” she said, mistily smiling. “But as for James—! How dared he talk to you like that? I wish very much that I had been present!”

“Oh, no Abby! It would have been much, much worse! And I couldn’t blame him. Not when he told me!”

“Told you what?” asked Abby sharply.

Selina turned her face away, shuddering. “ Celia ...!”

“So he told you that, did he? Of all the chuckleheaded dummies!” Abby exclaimed wrathfully.

“He felt himself obliged to tell me, and, or course, I quite see—because I thought it was just that Mr Calverleigh had been very wild when he was young, which is not what I could like,but still—! So he had to tell me the truth, and it has sunk me utterly, and I can’t help wishing that he hadn’t, for it would have been so much more comfortable, only very wrong, but I shouldn’t have known it was!”

“Put it out of your mind!” said Abby. “If it doesn’t concern me, it need not concern you! To be sure, it would be a little awkward if people knew of it, but they don’t, and, in any event, Celia wasn’t Rowland’s wife when it happened!”

Selina stared at her in horror. “Abby, you could not! A man who—Abby, think! No, no, promise me you won’t do it!” Tears began to roll down her cheeks. “Oh, Abby, don’t leave me! How could I live without you?”

“Hush, Selina! Nothing is decided yet. Don’t, I beg of you, fall into one of your—into a fuss! Come, let me put you into bed! You’re tired out. Fardle shall bring up your dinner to you, and—”

“Rabbit and onions!” uttered Selina, breaking into sobs of despair. “I couldn’t, I couldn’t!”

“Oh!” A wry smile twisted Abby’s lips. “No, I don’t think I could either.”

This was perhaps fortunate, for no opportunity was offered her to partake of this or any other dish. Selina’s sobs were the prelude to one of her dreaded fits of hysteria, and as this was accompanied by spasms and palpitations it was long before Abby could leave her. When Selina at last fell into an exhausted sleep, the only thing her equally exhausted sister wished for was her bed.

The morning brought confirmation of her suspicion that Lavinia had indeed been tattling. Mrs Grayshott came to Sydney Place to see Abby.

“For I could do no less than tell you, Abby, and beg your pardon! I have never been so vexed with Lavinia! And the worst of it is that she did it on purpose, and is not sorry for it! She told me what she had done the instant she came home yesterday knowing, of course, that I should be extremely displeased, but saying that she was Fanny’s friend, and that she knew she had been right to warn her.”

“Perhaps she was,” said Abby. “I don’t know. I don’t think Fanny quite believes it.”

“No, that also Lavinia told me. But Oliver thinks that even if she does not, the shock of discovering that it is true will have been lessened for the poor child. But it was not Lavinia’s business to have meddled! My dear, how tired you look!”

“I am a little tired,” owned Abby. “My sister is not quite well today, so ...”

She left the sentence unfinished, but she had said enough to send Mrs Grayshott back to Edgar Buildings in a state of such seething and impotent indignation that she informed her son, with unusual venom, that the sooner Miss Wendover’s numerous ailments carried her off the better it would be for Abby.

Hardly had she left Sydney Place than a sealed letter was delivered at the house. It was directed to Fanny, and brought to her in the drawing-room by Mitton. She took it with a shaking hand, made as if to tear it open, and then, with an inarticulate excuse, went out of the room.

She did not return. Abby, who had guessed that the missive must have been sent by Stacy Calverleigh, waited in growing disquiet for a full hour, and then went up to her room.

Fanny was seated by the window. She looked at Abby, but said nothing, and her face was so stony that Abby hesitated. Then she saw the helpless suffering in Fanny’s eyes, and went to her, not speaking, but folding her in her arms, and holding her close. Fanny did not resist, but for perhaps a minute she was as rigid as a statue Stroking the bright curls, Abby said huskily, as though to a much younger Fanny, who had tumbled down, and grazed her knees: “Never mind, my darling, never mind!”

She could have cursed herself for the inadequacy of these foolish words; but a quiver ran through Fanny, a rending sob broke from her, she turned in Abby’s arms, and clung to her, torn and shaken by the pent-up emotions of the past fortnight.

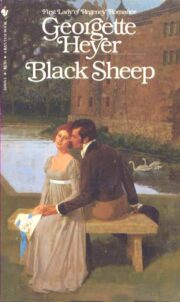

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.