That was the only ray of sunlight permitted for many days to break through the clouds surrounding Miss Abigail Wendover. She was enduring a time of trial, for which not Miles Calverleigh alone was responsible, but also her dear sister, and her cherished niece.

Influenza had left Fanny irritable and depressed. It was quite unnecessary for Dr Rowton to say that this uncharacteristic mood was attributable to her illness, and only what was to be expected. Abby knew that, but neither her own good sense nor the doctor’s reassurance made it easier for her to bear patiently the extremely wearing demands made upon her spirits by a convalescent who, when not sunk in gloom which affected everyone in her vicinity, peevishly found fault with everything, from the strength of the tea carried up to her room on her breakfast-tray, to the intolerable dullness of the books so hope-fully chosen by Abby at Meyler’s Library; or stared resentfully out of a rain-spotted window at a leaden sky, and sighed: “If only it would stop raining! If only I could go out!”

Poor little Fanny, said Selina, was quite unlike her merry self: an understatement which kindled a spark of amusement in Abby’s shadowed eyes. Dr Rowton told Abby, in his blunt way, that the sooner she stopped indulging Fanny the better it would be for herself, and Fanny too; but Dr Rowton did not know that there was another and deeper cause of Fanny’s crotchets than influenza. Abby did know, and even when she most wanted to slap her tiresome darling her heart went out to her. She was herself suffering from much the same malady, and if she had been seventeen, instead of eight-and-twenty, no doubt she would have abandoned herself to despair, just as Fanny was doing.

Fanny’s megrims might impose a severe strain upon Abby’s nerves, but it was Selina who rasped them raw, and broke down her command over herself.

Selina had seen Mrs Clapham, and she knew that it was all Too True. She had seen her in the Pump Room, whither a twinge of rheumatism had sent her (braving the elements in her carriage, with the hood drawn up) that morning. She had not at first known who she was, for how should she? She had merely been thinking that the bonnet she was wearing was in excellent style (though she had realized rather later that it bore too many plumes, and was of a disagreeable shade of purple, besides being a most unsuitable hat for a widow), when dear Laura Butterbank had whispered that she was Mrs Clapham.

“Which was a most unpleasant shock, as you may suppose, and almost brought on one of my distressing spasms. Fortunately, I had my vinaigrette in my reticule, for just when I was thinking that I did not at all like the look of her (not that I saw her face, for had her back turned to me, but one can always tell), whom should I see but young Calverleigh, making his way towards her, with that hoaxing smile on his face, all delight and cordiality as though he hadn’t been dangling after Fanny for weeks! And, Abby, he had the impudence to cut me! It’s of no use to say that he didn’t see me, because I am persuaded he did, for he took very good care not to look in my way again, besides going off with that vulgar creature almost immediately. When I recall the way he has been running tame in this house, inching himself in—at least, he did so until you came home and snubbed him and although I thought it a little unkind in you at the time, you were perfectly right, which 1 freely own—well, dearest, I was almost overpowered, and I trembled so much that I don’t know how I was able to reach the carriage, and if it hadn’t been for Mr Ancrum, who gave me his arm, very likely I never should have done so.”

She was obviously much upset. Abbey did what she could to soothe her agitation, but there was worse to come. That Woman (under which title Abby had no difficulty in recognizing the odious Mrs Ruscombe) had had the effrontery to come up to her to commiserate her, with her false, honeyed smile, on poor little Fanny’s humiliating disappointment. And not one word had she been able, in the desperation of the moment, to utter in crushing retort. Nothing had occurred to her!

Unfortunately, all too many retorts occurred to her during the succeeding days, and whenever she was alone with Abby she recalled exactly what Mrs Ruscombe had said, adding to the episode the various annihilating things she herself might have said, and reminding Abby of the numerous occasions when Mrs Ruscombe had behaved abominably. She could think of nothing else; and when, for the third time in one evening, she broke a brooding silence by saying, as though they had been in the middle of a discussion: “And another thing ...!”

Abby’s patience deserted her, and she exclaimed: “For heaven’s sake Selina, don’t start again! As though it wasn’t bad enough to have Fanny saying: ‘ If only it would stop raining!’ a dozen times a day! If you don’t wish to drive me into hysterics, stop talking about Mrs Ruscombe! What she said to you I have by heart, and as for what you might have said to her, you know very well you would never say any such things.”

She repented immediately, of course: indeed, she was horrified by her loss of temper. Begging Selina’s pardon, she said that she thought she was perhaps overtired.

“Yes, dear, no doubt you must be,” said Selina, “It is a pity you wouldn’t rest, as I repeatedly recommended you to do.”

Selina was not offended, oh, dear me, no! Just a little hurt, but she did not intend to say any more about that. She was sure Abby had not meant to wound her: it was merely that she was a trifle lacking in sensibility, but she did not intend to say any more about that either.

Nor did she, but her silence on that and every other topic was eloquent enough, and soon provided Abby with all that was needed to make her long passionately for Miles Calverleigh to come back, and to snatch her out of the stricken household without any more ado.

But it was not Miles Calverleigh who made an unexpected appearance in Sydney Place shortly before noon one morning. It was Mr James Wendover, carrying a small cloak-bag, and wearing the resentful expression of one forced, by the inconsiderate behaviour of his relations, to endure the discomforts of a night-journey to Bath on the Mail Coach.

It was Fanny, seated disconsolately by the window in the drawing-room, who saw him first. When the hack drew up, the hope that it had brought Stacy Calverleigh to her at last soared in her breast for one ecstatic moment, before it sank like a plummet at the sight of Mr Wendover’s spare, soberly clad figure. She exclaimed, startling Abby: “It is my uncle! No, no, I won’t—I can’t! Don’t let him come near me!”

With these distraught words, she rushed from the room, leaving Abby to make her excuses as best she might.

Forewarned, Abby betrayed neither perturbation nor astonishment when Mr Wendover presently entered the room, though she did say, as she got up from her chair: “Well, this is a surprise, “! What brings you to Bath, I wonder?”

Bestowing a perfunctory salute upon her cheek, he replied, in acrid accents: “ I must suppose that you know very well what has brought me, Abby! I may add that it has been most inconvenient—most inconvenient!—but since you have apparently run mad I felt myself compelled to undertake the journey! Where is Selina?”

“Probably drinking the waters, in the Pump Room,” replied Abby calmly. “She will be here directly, I daresay. Did you come by the Mail? What made it so late?”

“It was not late. I arrived in Bath punctually at ten o’clock and have already accomplished part of my mission. Why it should have been necessary for me to do so I shall leave it to your conscience to answer, Abby! If,” he added bitterly, “you have a conscience, which sometimes I am compelled to doubt!”

“It certainly seems as though I can’t have. However, I console myself with the reflection that at least I’m not as buffle-headed as the rest of my family!” said Abby brightly. “I collect that you came to try whether you could put an end to Fanny’s rather unfortunate flirtation with young Calverleigh. Now, if only you had warned me of your intention you would have been spared the journey! You have wasted your time, my dear James!”

His eyes snapped; he said, with a dry, triumphant laugh: “Have I? Have I indeed? I have already seen the young coxcomb, and I made it very plain to him that if he attempted to persuade my foolish niece into a clandestine marriage he would find himself taken very much at fault—very much at fault! I informed him that I should have no hesitation—none whatsoever!—in taking steps to have such a marriage annulled, and that under no circumstances should I disburse one penny of her fortune if she contracted an alliance without my sanction! I further informed him that he would have eight years to wait before deriving any benefit from that fortune!”

“I said you had wasted your time,” observed Abby, “I, too, informed him of these circumstances. I don’t think he believed me, and I am very sure he didn’t set much store by all thisbluster of yours. I have no great opinion of his intelligence but I fancy he is sufficiently shrewd to have taken your measure before ever he decided to make a push to captivate Fanny. Good God, if he had succeeded in eloping with Fanny you would have gone to any lengths to hush up the scandal, and so, depend upon it, he very well knows!”

An angry flush mounted into Mr Wendover’s thin cheeks “Indeed? In-deed! You are very much mistaken, my dear sister!I am aware that you fancy yourself to be awake upon every suit, but in my humble opinion you are as big a wet-goose as Selina! I don’t doubt for a moment that he paid little heed to anything you may have said to him: only a gudgeon could have failed to take your measure! When, however, he was confronted by me, the case was altered! I am happy to be able to inform you that this lamentable affair is now at an end!”

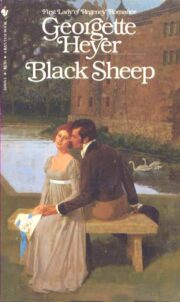

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.