“Quite a new come-out!” said Mrs Ruscombe, with her thin smile. “It doesn’t astonish me: I have always thought her a trifle bold.”

Abby was well aware that she had become overnight an object for curiosity; and so, within a couple of days, was Selina, who was thrown into what she called a taking by the arch efforts of one of her acquaintances to discover whether dear Miss Abigail was about to contract an engagement.

“I was never so much provoked in my life!’ she declared. ‘Such impertinence! I gave her a sharp set-down, as you may suppose! You and Mr Calverleigh—! If I hadn’t been vexed to death, I could have laughed in her face! Why, he isn’t even well-favoured, besides being quite beneath your touch—not, of course, by birth, but a man of most unsavoury reputation, though that Mrs Swainswick knows nothing about, and you may depend upon it I didn’t breathe a syllable to her. But how she could have the impudence to imagine—not but what I knew how it would be from the start, and I must beg you, dear Abby, to keep hint at a proper distance!”

Abby was quite as much vexed as Selina, but her indignation took a different form. “What a piece of work about nothing!” she said contemptuously. “I should rather think you would give that vulgar busy head a sharp set-down! What would be quite beneath my touch would be to pay the smallest attention to anything she, or others like her, may choose to say of me!”

If more than the vulgar Mrs Swainswick’s sly question had been needed to rouse the spirit of rebellion slumbering in her breast, it was provided by Mr Peter Dunston, who told her that he was afraid his mother had been quite shocked by the news of her escapade. “She is old-fashioned, you know. I need hardly assure you thatI do not share her sentiments! What you do could never be wrong, Miss Abigail. Indeed, if I had as little regard for your good name in Bath as Calverleigh I should have ventured to invite you to go to the play in my company!”

This put Abby in such a flame that if Mr Calverleigh had asked her to jaunter off to Wells with only himself as escort she would instantly have agreed to it. Not being informed of her state of mind, he did not do so; but as the two younger members of his party soon wandered off together, when they reached Wells, he did, in fact, become her only escort for a large part of the day, the only flaw to this agreeable arrangement being that none of the Bath quidnuncs knew anything about it. But this regret was soon forgotten in the pleasure of introducing, to a Cathedral she loved, one who was quick to appreciate its beauty, needing no prompting from her. She thought, in touching innocence, that in Miles Calverleigh she had found a friend, and a better one by far than any other, because his mind moved swiftly, because he could make her laugh even when she was out of charity with him, and because of a dozen other attributes which were quite frivolous—hardly attributes at all, in fact—but which added up to a charming total, outweighing the more important faults in his character. She was aware of these, but she could find excuses for his cynicism, and even for the coldness of heart which made him look upon the problems or the troubles besetting other people with a detachment so profound as to seem inhuman. It was no wonder that twenty years of exile had made him uncaring, the wonder was that he was not embittered. As for the life he had led during those years, she did not suppose that virtue had played a noticeable part in it, but she felt it to be no concern of hers. Nor did she wish to know how many mistresses he had had or what excesses he might have committed: the past might keep its secrets, leaving her to the enjoyment of the present.

If she spared a thought for her niece, whom she had so reprehensibly allowed to escape from her chaperonage, it was merely to hope that Fanny was enjoying the day as much as she was. The child had not been in spirits at the start of the expedition. She had tried to hide it with rather more than her usual vivacity, but her gaiety had had a brittle quality. Abby dared not hope that she had quarrelled with Stacy; probably she was downcast because she had begun to despair of winning her family’s consent to her projected engagement. Perhaps Oliver would succeed in coaxing her out of the dumps; perhaps, if Lavinia, who had not yet learnt to withhold confidences from those she loved, had told him the story of Fanny’s infatuation, he might even venture to offer her a little advice. Abby had no doubt that it would be good advice, and very little that advice from a man with whom Fanny stood on friendly terms would be listened to far more readily than advice from an aunt.

Oliver did know the story, but the only advice he gave was addressed to his sister. He had listened to her sentimental outpourings in silence, disappointing her by saying quietly, when she had done: “Lavvy, you shouldn’t repeat what Fanny tells you.”

“Oh, no! Only to you—and Mama, of course!”

“Well, to Mama, perhaps, but not to me. I let you do so only because I already knew, from Mama, that Fanny had formed an—an attachment which her aunt dislikes. And because I fancy you are much in sympathy with her.”

“Yes, indeed I am!” she said earnestly. “It is the most affecting thing imaginable, for they fell in love the first time they met! He is so handsome, too, and has such an air! And merely because he hasn’t the advantage of fortune—as though it signified, when Fanny is positively rolling in riches!—”

“It isn’t that,” he interrupted, hesitating a little. “Not wholly that.”

“Oh, you are thinking that he was used to be very wild, and expensive, but—”

“No, I’m not, Lavvy. I know nothing about him, except that—” Again he hesitated; and then, as she directed a look of puzzled enquiry at him, said, with a little difficulty: “He isn’t a halfling, you know, or a greenhorn. He must be a dozen year older than Fanny, and a man of the world into the bargain.”

“Yes!” said Lavinia enthusiastically. “Anyone can see he is of the first stare, which makes it so particularly romantic that he should have fallen in love with Fanny! I don’t mean to say that she isn’t ravishingly pretty, because she is, but I should think there must be scores of fashionable London-girls on the catch for him, wouldn’t you?”

“Listen, Lavvy!” he said. “The thing is that he hasn’t behaved as he ought! A man of honour don’t flummery a girl into meeting him upon the sly, and he don’t pop the question to her without asking leave of her guardian!”

“Oh, Oliver, you are repeating what Mama says! How can you be so stuffy? Next you will be saying that Fanny ought to wait meekly until her guardian bestows her on a man of his choice!”

“I shan’t say anything of the sort. But I’ll tell you this, Lavvy: if Calverleigh had made you the object of his havey-cavey attentions I’d knock his teeth down his throat!”

Startled, and rather impressed, she said: “Good gracious! Would you? Well!”

“Try to, at all events,” he said, laughing. “It’s what any man would do.”

She did not look to be entirely convinced. He put his arm round her, and gave her a brotherly hug. “It isn’t for me to interfere: I haven’t the right. But you’ll be a poor friend to Fanny if you don’t make a push to persuade her not to throw her cap over the windmill. That’s the way to return by Weeping Cross.” He had said no more, and how much of what he had said was repeated to Fanny he had no means of knowing, because he was wary of betraying to his sister that he took far more than a neutral interest in the affair, and so would not ask her. Between himself and Fanny it was never discussed, and much as he longed to beg her not to throw herself away on a court-card who, in his view, was an ugly customer if ever he saw one, it did not come within his province to meddle in the affairs of a girl who would never be more to him than an unattainable dream, or within his code of honour to cry rope upon a fellow behind his back. Given the flimsiest of excuses—if only he had been even remotely related to Fanny!—he would speedily have cut the fellow’s comb for him; for although he was not yet in high force he had no doubt of his ability to draw the elegant Mr Stacy Calverleigh’s cork, besides darkening both his daylights, before tipping him a settler. His hands clenched themselves instinctively into two bunches of purposeful fives as he allowed his fancy to dwell for a moment on the pleasing vision of a regular set-to with Stacy. He was innately chivalrous, but he would have no compunction whatsoever in milling down this sneaking rascal, who, if he had ever come to handy-blows in his life (which Mr Grayshott doubted) was certainly no match for one whose science, and punishing left, had won fame for him in the annals of his school and college. But only for a moment did the vision endure: even the excuse of rivalry was denied him. Mr Grayshott, setting out for India in high hope, and eager determination to prove himself worthy of his uncle’s trust, had been defeated by his constitution, and saw himself as a failure. Mr Balking had told him not to tease himself about the future, and not to take it so much to heart that his health had broken down. “For how could you help it? I wish I’d never sent you to Calcutta—except that the experience you’ve gained will stand you in good stead. I’ve a place for you in the London house, but time enough to talk of that when you’re on your pins again.”

Mr Balking had been kindness itself, but Oliver, his spirits as much as his gaunt frame worn down by recurrent fever, foresaw that he was destined to become a clerk in the counting-house from which lowly position he was unlikely to rise for many dreary years. He had set no store by Uncle Leonard’s assurances that he was very well satisfied with his work in Calcutta: that was the sort of thing that an affectionate uncle might be expected to say. He had reached Bath in a state of deep depression, but as his health improved so did his spirits, and he began to think that it might not be so very long before he worked his way up to a position of trust. When he was able to look back dispassionately over the two years he had spent in India, he thought that perhaps his uncle really was satisfied with his progress there. He had found his work of absorbing interest, and knew that he had a talent for business. In fact, if he had been a windy-wallets, boasting of his every small success, he would have said that he had done pretty well in the Calcutta house. As he was a diffident, and rather reticent young man, he maintained a strict silence on the subject, and waited, in gradually increasing hopefulness, for the day when his doctor should pronounce him well enough to apply himself once more to business.

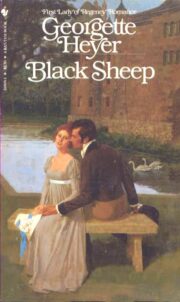

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.