“But he has no fortune!” she protested. “He is connected with trade, too, which James would very much dislike.”

“Oh, would he? My sweet simpleton, let James get but one whiff of an East India merchant’s heir in Bath, and he won’t lose a moment in setting snares to catch such a prize!”

She disregarded this, exclaiming: “You must be mistaken! Oliver has no such expectations! Indeed, he feels that he has miserably disappointed his uncle.”

“Not he! Balking thinks the world of him, and means to take him into partnership as soon as he’s in good point again.”

“No, does he indeed? I am so glad! But as for thinking of his marrying Fanny, that’s moonshine! I own, I should be thankful if she did fall in love with him—though she is much too young for marriage—but there’s no likelihood of her doing so while she’s besotted of your odious nephew.”

“You know, if you mean to talk of nothing but your totty-headed niece and my odious nephew I shall have a colic,” he informed her.

“Well, of all the detestably uncivil things to say—!” she gasped.

“If it comes to that, what a detestably boring thing to talk about!”

“I bee your pardon!” she said icily. “To me, it is a subject of paramount importance!”

“Yes, but it isn’t so to me.

Since Miss Butterbank came up at that moment, to tell her that dear Miss Wendover was ready to go home, she was prevented from uttering the retort that rose to her lips; but when her graceless tormentor presented himself in Sydney Place on Saturday she received him with a good deal of chilly reserve. As far as she could discover, this had no effect on him whatsoever. He devoted himself largely to Selina, listening good-naturedly to her rambling discourse, until she embarked on a catalogue of the various illnesses suffered by herself and several of her friends when he retaliated by telling her of the terrible diseases rife in India. From there it was a small step to a description of such aspects of Indian life, climate, and scenery as were most calculated to hold spellbound a middle-aged lady of enquiring mind and credulous disposition. Selina mellowed perceptibly under this treatment, and told Abby, when they had withdrawn from the dining-room, leaving their guest to enjoy a glass of port in solitary state, that really Mr Calverleigh was a most interesting man. “I declare I feel as if I had actually been to India myself!” she said. “So vivid, and droll—all those strange customs! Tigers and elephants, too—not that I should care to live with tigers, and although I believe elephants are wonderfully docile I don’t think I could ever feel myself at ease with them. But so very interesting—quite like a fairy story!”

Abby, who thought that some of Mr Calverleigh’s tales were exactly like fairy stories, was able to agree to this with perfect sincerity. She had every intention of maintaining her punctilious civility, and might have done so had he not said, as he took his seat beside her in the carriage he had hired for the evening: “I wish I had ordered a hot brick to be provided.”

“Thank you, but there was not the least need to do so: I don’t feel at all cold.”

“I daresay icebergs don’t feel cold either, but I do!”

She was betrayed into a smothered choke of laughter, whereupon he added: “From having lived so long in a hot climate, you understand.”

“I understand you perfectly, sir, and shall take leave to tell you that there’s neither truth nor shame in you!”

“Well, not much, perhaps!” he owned.

Since this quite overset her gravity, she was obliged to relent towards him, and by the time Beaufort Square was reached their former good relationship had been so well restored that she was able to look forward to an evening of unalloyed enjoyment, which not even the surprised stares of several persons with whom she was acquainted seriously disturbed. Mr Calverleigh proved himself to be an excellent host: not only had he hired one of the handsomely appointed first-tier boxes, but he had also arranged for tea and cakes to be brought to it during one of the intervals. Abby said appreciatively: “How comfortable it is not to be obliged to inch one’s way through the press in the foyer! You are entertaining me in royal style, Mr Calverleigh!”

“What, with cat-lap and cakes? If I entertained you royally I should give you pink champagne!”

“Which I shouldn’t have liked half as well!”

“No, that’s why I didn’t give it to you.”

“I expect,” said Abby, quizzing him, “it is invariably drunk in India—even for breakfast! Another of the strange customs you described to my sister!”

He laughed. “Just so, ma’am!”

“Well, if she recounts your Canterbury tales to young Grayshott you will have come by your deserts! He will refute them, and you will look no-how!”

“No, no, you wrong the boy! He’s not such a clodpole!”

“Incorrigible! It was a great deal too bad of you to make a May-game of poor Selina.”

“Oh, I didn’t! It was made plain to me that she has a very romantical disposition, and delights in the marvellous, so I did my best to gratify her. Turning her up sweet, you know.”

“Trying how many brummish stories you could persuade her to swallow is what you mean! How many did you tell me?”

He shook his head. “None! You should know better than to ask me that. I told you once that I don’t offer you Spanish coin, I’ll tell you now that I don’t offer you Canterbury tales either “ He saw the startled look in her eyes, the almost imperceptible gesture of withdrawal, and added simply: “You wouldn’t believe ‘em.”

This made her laugh again, but for a moment she had indeed been startled, perceiving in his light eyes a glow there could be no mistaking. She had felt suddenly breathless, and embarrassed, for she had hitherto suspected him of pursuing nothing more serious than an idle flirtation. But there had been a note of sincerity in his voice, and his smile was a caress. Then, just as she was thinking: This will never do! he had uttered one of his impishly disconcerting remarks, which left her wondering whether she had allowed her imagination to mislead her.

His subsequent behaviour was irreproachable, and there was so little of the lover in his manner that her embarrassment swiftly died. She reflected that he was really a very agreeable companion, with a mind so much akin to her own that she was never obliged to explain what she meant by some elliptical remark, or to guard her tongue for fear of shocking him. He was attentive to her comfort, too, but in an everyday style: putting her shawl round her shoulders without turning the office into an act of homage; and neither pressing nor retaining her hand when he assisted her to enter the carriage. This treatment made her feel so much at her ease that when he asked her casually if she would join an expedition to Wells, and show him the cathedral there, she had no hesitation in replying: “Yes, willingly: going to Wells, to see the knights on horseback, has always been a high treat to me!”

“What the deuce are they?” he enquired.

“A mechanical device—but I shan’t tell you any more! You shall see for yourself! Who else is to join your expedition?”

“I don’t know. Yes, I do, though! We’ll take Fanny and young Grayshott!”

She smiled, but said: “You should invite Lavinia too.”

“Oliver wouldn’t agree with you. Nor do I. There will be no room in the carriage for a fifth person.”

“She could take my place. Or even Mrs Grayshott. She would enjoy the drive.”

“She would find it too fatiguing. Can’t you think of anyone else to take your place?”

“Yes, Lady Weaverham!” she said instantly, a gurgle of merriment in her throat.

“No, I think, if I must find a substitute for you, I shall invite your sister’s bosom-bow—what’s her name? Buttertub? Tallow-faced female, with rabbit’s teeth.”

“Laura Butterbank!” said Abby, in a failing voice. “Odious, infamous creature that you are!”

“Oh, I can be far more odious than that!” he told her. “And if I have any more wit and liveliness from you, Miss Abigail Wendover, I’ll give you proof of it!”

“Quite unnecessary!” she assured him. “I haven’t the least doubt of it!”

She could not see his face in the darkness of the carriage, but she knew that he was smiling. He said, however, in stern accents: “Will you go with me to Wells, ma’am, or will you not?”

“Yes, sir,” said Abby meekly. “If you are quite sure you wouldn’t prefer Miss Butterbank’s company to mine!”

The carriage had drawn up in front of her house. Mr Calverleigh, alighting from it, and turning to hand her down, said: “I should, of course, but having already invited you I feel it would be uncivil to fob you off.”

“Piqued, repiqued, and capoted!” said Abby, acknowledging defeat

Chapter X

The visit to the theatre produced its inevitable repercussions. Only such severe critics as Mrs Ruscombe saw anything to shock them in it, but it was surprising how quickly the word sped round Bath that Mr Miles Calverleigh was becoming extremely particular in his attentions to Miss Abigail Wendover. There was nothing in this to give rise to speculation, for Abby had never lacked admirers; but considerable interest was lent to the affair by what was generally considered to be her encouragement of the gentleman’s pretensions.

“Only think of her going to the play with him all by herself! When Lady Templeton told me of it I could only stare at her! I’m sure she has never done such a thing before!” said Mrs Ancrum.

“Mark my words,” said Lady Weaverham, “it’s a Case! Well, I’m sure I wish them both very happy!”

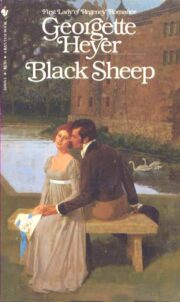

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.