“Oh, you’re quite mistaken! I am precisely such a care-for-nobody.”

“But I’m your nephew! You can’t want me to be rolled-up!”

“It’s a matter of indifference to me.”

“Well, upon my soul!” Stacy exploded.

“As it would be to you if that fate befell me,” said Miles, slightly smiling. “Why should either of us care a straw for what becomes of the other?”

Stacy gave an uncertain laugh. “Damme if ever I met such a queer-card as you are!”

“Don’t let it distress you! Comfort yourself with the reflection that it would do you no good if I did choose to recommend you to Miss Abigail Wendover.”

“She would listen to you,” Stacy argued. “And if she could be brought to consent to the marriage I don’t doubt that Wendover would do so too. He doesn’t concern himself with Fanny—never has done so!—and his wife don’t like her. She isn’t going to bring her out next year! I’ll lay you a guinea to a gooseberry she’d be glad to see Fanny safely buckled before she brings out her own daughter!”

“Then why waste your eloquence on me? Address yourself to Mrs James Wendover!”

“With Miss Abigail against me?” Stacy said scornfully. “I’m not such a clunch!”

“My good boy, if you imagine that James Wendover could be persuaded by his sister, or by anyone else, to consent to Fanny’s marriage to a basket-scrambler, you’re a lunatic!” said Miles brutally.

Stacy drained his fourth glass. “What’ll you wager against the chance that he’ll find himself forced to consent?” he demanded, his utterance a little slurred. “Got to force him to—nothing else to be done to bring myself about!”

“What about Danescourt?”

Stacy stared at him rather owlishly. “Danescourt?”

“Why don’t you sell it?” asked Miles coolly.

“Sell it! I’m going to save it! Before they can foreclose!”

“As bad as that?”

“Yes, damn you! Besides—I don’t want to sell it!”

“Why not? You told me you hated it!”

“Yes, but it means something. Gives one consequence. Place in the country, you know: Calverleigh of Danescourt! No substance without it—bellows to mend with me!”

“It appears to be bellows to mend with you already,” said his uncle caustically.

Chapter IX

Mr Stacy Calverleigh, having slept off the result of his potations, awoke, far into the following day, with only the haziest recollections of what might have passed between himself and his uncle. So much did he plume himself on his ability to drink all other men under the table that he ascribed the circumstance of his having been put to bed by the boots to the vile quality of the brandy supplied by the White Hart; and when he encountered Mr Miles Calverleigh in Milsom Street, two days later, he laughingly apologized for it, and for its effect upon himself, describing this as having been rendered a trifle above oar. He spoke gaily, but under his insouciance there lurked a fear that he might have been betrayed into indiscretion. He said that he hoped he had not talked a great deal of nonsense, and was reassured by his uncle’s palpable lack of interest He then ventured to express the hope that Miles would not betray him to the ladies in Sydney Place, saying: “I should find myself in the briars if Miss Abigail even suspected that I do, now and then, have a cup too much!”

“What a good thing you’ve warned me not to do so!” responded Miles sardonically. “Entertaining females with accounts of jug-bitten maunderings is one of my favourite pastimes.”

He left Stacy with one of his careless nods, and strode on down the street, bound for the Pump Room. Here he found all the Wendovers: Abby listening with an expression of courteous interest to one of General Exford’s anecdotes; Fanny making one of a group of lively young persons; and Selina, with Miss Butter-bank in close attendance, receiving the congratulations of her friends on her emergence from seclusion. After an amused glance in Abby’s direction, Miles made his way towards Selina, greeting her with the ease of long friendship, and saying, with his attractive smile: “I shan’t ask you how you do, ma’am: to enquire after a lady’s health implies that she is not in her best looks. Besides, I can see that you are in high bloom.”

She had watched his approach rather doubtfully, but she was by no means impervious to flattery, or to his elusive charm, and she returned the smile, even though she deprecated his compliment, saying: “Good gracious, sir, at my age one doesn’t talk of being in high bloom! That is quite a thing of the past—not that I ever was—I mean, no more than passable!”

“Oh, my dear Miss Wendover, how can you say so?” exclaimed Miss Butterbank, throwing up her hands, “ Such a farradiddle I declare I never heard! But you are always so modest! I must positively beg Mr Calverleigh to turn a deaf ear to you!”

Since he was at that moment asking Mrs Leavening how she had prospered that morning in her search for lodgings, he had no difficulty in obeying this behest. The only difficulty he experienced was how to extricate himself from a discussion of all the merits, and demerits, of the several sets of apartments Mrs Leavening had inspected. But having agreed with Selina that Axford Buildings were situated in a horrid part of the town, and with Mrs Leavening that Gay Street was too steep for elderly persons, he laughed, and disclosed with disarming candour that he knew nothing of either locality. “But I believe people speak well of Marlborough Buildings,” he offered. “Unless you would perhaps prefer the peace and quiet of Belmont?”

“Belmont?” said Selina incredulously. “But that would never do! It is uphill all the way! You can’t be serious!”

“Of course he isn’t, my dear!” said Mrs Leavening, chuckling. “He hasn’t the least notion where it is. Now, have you, sir?”

“Not the least! I shall make it my business to find out, however, and I’ll tell you this evening, ma’am,” he promised.

He then bowed slightly, and walked away. Selina, taking umbrage at the suggestion that there was any part of Bath with which she was not fully acquainted, exclaimed: “Well, I must say I think him a very odd creature! One might have supposed—not that I know him at all well, and one shouldn’t judge anyone on a angle morning-visit, even in his riding-dress, which I cannot like—though Abby assures me he won’t dine with us in it—but his manners are very strange and abrupt!”

“Oh, he is certainly an original, but so droll!” said Mrs Leavening. “We like him very much, you know, and find nothing in his manners to disgust us.”

“Exactly what I have been saying to dear Miss Wendover!” interpolated Miss Butterbank. “Anyone of whom Miss Abby approves cannot be other than gentlemanlike!”

“Yes, but it is not at all the thing for her to be going to the play in his company. At least, it doesn’t suit my sense of propriety, though no doubt my notions are antiquated, and, of course, Abby is not a girl, precisely, but to talk as if she was on the shell is a great piece of nonsense!”

Mrs Leavening agreed to this, but as her husband came up at that moment Selina did not tell her old friend that Abby, not content with accompanying Mr Calverleigh to the theatre, had actually invited him to dine in Sydney Place.

This bold stroke had quite overset Selina. The news that Mr Calverleigh had been so kind as to invite Abby to go to the play she had received placidly enough, if with a little surprise: it seemed very odd that a single gentleman should get up a party, but no doubt he wished to return the hospitality of such ladies as Mrs Grayshott, and Lady Weaverham. Were the Ancrums going as well?

Abby was tempted, for a craven moment, to return a noncommittal answer, but she overcame the impulse, and replied in an airy tone: “Oh, it is not a party! Do you think I ought not to have accepted ? I did hesitate, but at my age it is surely not improper? Besides, the play is The Venetian Outlaw, which I particularly want to see! From some cause or another I never have seen it, you know: once I was ill, when it was put on here, and once I was away from home; but you went to see it twice, didn’t you ? And were in raptures!”

“Yes, but not with a gentleman!”Selina said, scandalized. “Once,I went with dear Mama, only you were too young then; and the second time Lady Trevisian invited me—or was that the third time? Yes, because the second time was when George and Mary were with us, and you had a putrid sore throat, and so could not go with us!”

“This time I am determined not to have a putrid sore throat!”

“No, indeed! I hope you will not! But Mr Calverleigh must invite some others as well! I wonder he shouldn’t have done so. It argues a want of conduct in him, for it is not at all the thing, and India cannot be held to excuse it, because there are no theatres there—at least, I shouldn’t think there would be, should you?

“No, dear. So naturally Mr Calverleigh couldn’t know that he was doing anything at all out of the way, poor man! As for telling him that he must invite others as well as me, I hope you don’t expect me to do so! That would indeed be improper! And, really, Selina, what possible objection can there be to my going to the play under the escort of a middle-aged man? Here, too, where I am well known, and shall no doubt meet many of our friends in the theatre!”

“It will make you look so—so particular, dearest! You would never do so in London! Of course, Bath is a different matter, but worse! Only think how disagreeable it would be if people said you were encouraging Mr Calverleigh to dangle after you!”

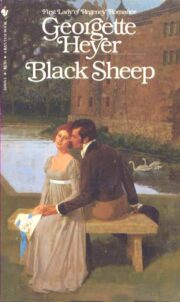

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.