“Does he, indeed?” replied Mrs Grayshott, a good deal amused. “I suspect he is what Oliver calls a complete hand! You know, my dear, I must own that I am glad to see you on such good terms with him, for it has been very much on my conscience that I almost forced him upon you, which, as I hope you know, I never meant to do!”

“Oh, I know you didn’t, ma’am! I wish you won’t give it another thought. Sooner or later I must have met him, you know.”

“And you like him? I was afraid that his free-and-easy manners might offend you.”

“On the contrary! They amuse me. He is certainly an original!”

Mrs Grayshott smiled, but said rather wistfully: “Why, yes! But not only that! He is so very kind! He makes light of the services he rendered Oliver throughout that weary voyage, but I’ve heard the truth from Oliver himself. But for Mr Calverleigh’s unremitting care I don’t think that my poor boy would have survived, for he tells me that he suffered a recrudescence of that horrible fever within two days of having been carried aboard! It was Mr Calverleigh, rather than the ship’s surgeon, who preserved his life, his long residence in India having made him far more familiar with the disorder than any ship’s surgeon could be! I must be eternally obliged to him!” Her voice shook; she overcame the little surge of emotion, and said, with an effort at liveliness: “And, as though he bad not done enough for me, what must he do but procure tickets for this concert tonight, and positively bully me into accompanying him! Something I must have said gave him the notion that I should very much like to hear Neroli, and I think it particularly kind in him to have given me the opportunity to do so, because I am afraid he is not himself a music-lover.”

Having very good reason to suppose that Mr Calverleigh’s kindness sprang from pure self-interest, Abby was hard put to it to hold her tongue. It was perhaps fortunate that he rejoined them at this moment, thus putting an end to any further discussion of his character. She accepted the tea he had brought, with a word of thanks and a charming smile, but could not resist the impulse to ask him if he was not ravished by Neroli’s voice.

He replied promptly: “Not entirely. A little too much vibrato, don’t you agree?”

“Ah, I perceive that you are an expert!” said Abby, controlling a quivering lip. “You must enlighten my ignorance, sir! What does that mean, if you please?”

“Well, my Latin is pretty rusty, but I should think it means to tremble,” he said coolly. “She does, too, like a blancmanger. And much the same shape as one,” he added thoughtfully.

“Oh, you dreadful creature!” protested Mrs Grayshott, bubbling over. “I didn’t mean that,when I said I thought she had rather too much vibrato! You know I didn’t!”

“I thought she had too much of everything,” he said frankly.

Mrs Grayshott cried shame upon him; but Abby, caught in the act of sipping her tea, choked.

When he presently restored her to her own party, she was spared the necessity of introducing him to Mrs Faversham by that lady’s greeting him by name, and with a gracious smile: Lady Weaverham had already performed that office, in the Pump Room that morning.

Mr Faversham said, taking his seat beside Abby: “So that’s young Calverleigh’s uncle!” He looked critically after Mr Calverleigh’s tall, retreating figure. “Got the look of a care-for-nobody, but I like him better than his nephew: too insinuating by half, that young man!”

“You don’t like him, sir?”

“No, I can’t say I do,” he replied bluntly. “Fact of the matter is I set no store by these young sprigs of fashion! My wife calls me an old fogey: daresay you will too, for the ladies all seem to have run wild over him! Haven’t met him yet, have you?”

“No, that pleasure hasn’t been granted me,” she said, in a dry tone.

It was to be granted her on the following day. Mr Stacy Calverleigh, coming down from London on the mail-coach, arrived at the White Hart midway through the morning, and stayed only to change his travelling-dress for the corbeau-coloured coat of superfine, the pale pantaloons, and the gleaming Hessian boots of the Bond Street beau, before setting out in a hack for Sydney Place.

The ladies were all at home, Abby, who had just come in from a visit to Milsom Street, submitting to her sister’s critical inspection some patterns of lace; Selina reclining on the sofa; and Fanny wrestling with the composition of an acrostic in the back drawing-room. She did not immediately look up when Mitton announced Mr Calverleigh, but as Stacy advanced into the room he spoke, saying in a rallying tone: “Miss Wendover! What is this I hear about you? Mitton has been telling me that you have been quite out of frame since I saw you last! I am so very sorry!”

His voice brought Fanny’s head up with a jerk. She sprang to her feet, and almost ran into the front room, exclaiming with unaffected joy: “ Stacy! Oh, I thought it was only your uncle!”

She was holding out her hands to him, and he caught them in his, carrying first one and then the other to his lips with what Abby, observing her niece’s fervour with disapprobation, recognized as practised grace. “You thought I was my uncle? Now, I begin to suspect that it is you rather than Miss Wendover who must be out of frame!” he said caressingly. “Indeed I am not my uncle!” He gave her hands a slight squeeze before releasing them, and moving forward to drop on his knee beside the sofa. “Dear Miss Wendover, what has been amiss? I can see that you are sadly pulled, and my suspicion is that you have been trotting too hard!”

The demure laughter in his voice robbed his words of offence. Selina all too obviously succumbed to the charm of a personable and audacious young man, scolding him for his impertinence, in the manner of an indulgent aunt, and favouring him with an account of her late indisposition.

Abby was thus afforded an opportunity to study him at her leisure. She thought that it was easy to see why he had made so swift a conquest of Fanny: he was handsome, and he was possessed of ease and address, his manners being distinguished by a nice mixture of deference and assurance. Only in the slightly aquiline cast of his features could she detect any resemblance to his uncle: in all other respects no two men could have been more dissimilar. His height was not above the average, but, in contrast to Miles Calverleigh’s long, loosely-knit limbs, his figure was particularly good; he did not, like Miles, look as if he had shrugged himself into his coat: rather, the coat appeared to have been moulded to his form; the ears of his collars were as stiff as starch could make them; his neckcloths were never carelessly knotted, but always beautifully arranged, whether in the simple style of the Napoleon, or the more intricate folds of the Mathematical; and he showed exquisite taste in his choice of waistcoats. Such old-fashioned persons as Mr Faversham might stigmatize him as a tippy, a dandy, a bandbox creature, but their instinctive dislike of the younger generation of dashing blades on the strut earned them too far: Stacy Calverleigh was a smart, but not quite a dandy, for he affected few of the extravagances of fashion. His shirt-points might be a little too high, his coats a trifle too much padded at the shoulder and nipped in at the waist, but he never overloaded his person with jewellery, or revolted plain men by helping himself to snuff with a silver shovel.

His profile, as he knelt beside the sofa, was turned towards Abby, and she was obliged to acknowledge that it was a singularly handsome profile. Then, when Fanny seized the opportunity offered by a pause in Selina’s garrulity to present him to her other aunt, and he turned his head to look up at Abby, she thought him less handsome, but without quite knowing why.

He jumped up, exclaiming, with a boyishness which, to her critical ears, had a false ring: “Oh! This is a moment to which I’ve been looking forward—and yet dreading! Your very humble servant, ma’am!”

“Dreading?” said Abby, lifting her brows. “Were you led to suppose I was a gorgon?”

“Ah, no, far from it! A most beloved aunt!”

His ready smile curled his lips as he spoke, but Abby, looking in vain for a trace of the charm which awoke instant response in her when the elder Calverleigh smiled, realized that it did not reach his eyes. She thought they held a calculating look, and suspected him of watching her closely to discover whether he was making a good or a bad impression on her.

She said lightly: “That doesn’t seem to be a reason for your dread, sir.”

“No, and it’s moonshine!” Fanny said. “How can you talk such nonsense, Stacy?”

“It isn’t nonsense. Miss Abigail loves you, and must think me unworthy of you—oh, an impudent jackstraw even to dream of aspiring to your hand!” He smiled again, and said simply: “I think it too, ma’am. No one knows better than I how unworthy I am.”

A sentimental sigh and an inarticulate murmur from Selina showed that this frank avowal had moved her profoundly. Upon Abby it had a different effect. “Trying to take the wind out of my eye, Mr Calverleigh?” she said.

If he was disconcerted he did not betray it, but answered immediately: “No, but, perhaps—the words out of your mouth?”

Privately, she gave him credit for considerable adroitness, but all she said was: “You are mistaken: I am not so uncivil.”

“And it isn’t true!” Fanny declared passionately. “I won’t permit anyone to say such a thing—not even you, Abby!”

“Well, I haven’t said it, my dear, nor am I likely to, so there is really no need for you to fly up into the boughs! Tell me, Mr Calverleigh, have you made the acquaintance of your uncle yet?”

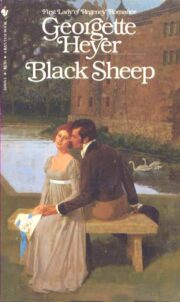

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.