AIDA STEPPED OUT OF THE PIERCE-ARROW IN FRONT OF A GRAY green Queen Anne mansion. Four stories high, it was twice as big as the neighboring houses and looked like something out of a fantasy tale, with steeply gabled roofs, fish-scale shingles, bay windows, and a round, turreted tower. Like the other homes in this area, it had no yard to speak of—only a short iron fence and a shallow border of grass separating its massive girth from the public street. And like virtually everything else in this city, it was built on a steep slant with half the bottom floor disappearing into the hill.

“Goodness, it’s grand,” she murmured to herself, craning her neck to take it all in. She spotted two men stationed at either fence corner—security, she supposed. “He lives in this big house all by himself?”

“His younger sister, too. The help. His brother, when he comes home on holidays.”

Ah, no mother, then. Maybe she died in the accident, too. No wonder he didn’t like talking about it.

Bo led her down a narrow sidewalk in front of the house, up a short flight of steps to a covered portico that harbored a wide green door. As he reached for the handle, the door swung inward to a tall, pale, silver-haired woman. She wore an apron tied around her middle and a look of aloofness that was only slightly warmed by the pink of her cheeks. She studied Aida critically from head to foot for a moment too long while Bo removed his cap.

“Greta, this is Miss Aida Palmer.”

The woman gave her a funny smile that Aida couldn’t make heads or tails of. “Miss Palmer,” she said in a birdlike voice with a heavy Scandinavian lilt. “Mr. Magnusson is waiting for you in his study. Come. I will take you.”

Aida stepped into a spacious entry, bigger than her entire apartment, with a high ceiling that opened up to the second floor and dark wood floors below her feet. A labyrinth of rooms sprouted in every direction.

“I’ll be eating lunch down here in the kitchen,” Bo said. “When you’re ready to go, Winter will call me and I’ll drive you back home. I’ve got business in Chinatown later.”

She thanked him before he headed down a hallway and disappeared.

Aida followed Greta’s impressively fast strides through the entry. At first she thought they were headed up the massive staircase, but Greta veered to the side and stopped in front of a black elevator, a small rectangular contraption that looked like an Art Nouveau metal birdcage, with scrolling whiplash curves.

“I’ve never seen an elevator inside a private home,” Aida remarked upon entering.

Greta shut the scissor gate, then the cage door, and operated a lever. “The Magnussons are fond of wasting monies.”

Well. Aida didn’t know what to say to that. The rickety elevator groaned and whined as it made a shaky ascent to a highly polished dark hallway on the fourth floor.

Greta led her to a set of carved doors, guarded by a man sitting in a chair, playing solitaire on a folding wooden tray table; he doffed his cap when they passed by. A wide room lay beyond, filled with standing bookshelves, a large desk, and a billiards table. Several windows on the far wall offered an expansive view of the city and the foggy bay.

A cozy sitting area surrounded an oversized fireplace. The fire was lit, and sitting on a brown leather couch reading the San Francisco Chronicle was Winter Magnusson.

Surely he heard the elevator or their steps echoing down the hallway, but he remained engrossed in his reading, legs crossed, lounging in his shirtsleeves. His suit jacket lay folded on the back of the couch.

“Winter.” Greta’s singsong accent made his name sound more like “Veen-ter.”

He glanced up from the paper and looked straight at Aida. His eyes narrowed slowly, like someone playing blackjack who’d just been dealt a ten and an ace.

And Aida felt like she’d just lost all her chips along with the shirt off her back.

“You came,” he said in his low cello-note voice.

“I hope you won’t find a way to make me regret that.”

He looked amused but didn’t smile. “I’ll try to keep my clothes on this time.”

If he was trying to embarrass her in front of his housekeeper, he’d have to try harder. “I’m only here because you’re paying me an exorbitant fee for a house call.”

“Worth every cent.” He folded up his newspaper. “Hungry?”

“Not sure,” she replied honestly. She had been, but now her brain was sending some confused signal to her body, preparing her to either become sick or run for her life. Why was her heart beating so fast? She could feel her blood pulsing at her temples.

“Greta, leave us. I’ll call when we’re ready for a tray,” Winter said, prompting the housekeeper to exit the room as he tossed the folded newspaper aside and stood.

Aida suddenly remembered just how big he was, and took him in from head to foot as he approached: crisp white linen shirt, black necktie with horizontal bands of silver, pin-striped gray vest anchored by the gold chain of his pocket watch, black wing tips. His flat-front charcoal trousers were so accurately tailored, they hugged the muscle of his thighs in an almost obscene manner. She liked this.

“You’re looking . . .” Enormous. Handsome. Intimidating. “Recovered,” she said.

“I’m feeling a hell of a lot better. Are you planning on dashing right back out? Or did you not trust Greta with your coat?”

“She didn’t offer to take it.”

“Since she’s failed at her duties, allow me.” He said this as if it were some great chore and made an impatient gesture for her to comply, but she caught a curious gaze flicking toward her under the false front of seemingly bored, hooded eyes.

She set down her handbag on a small table by the door and unbuttoned her coat. As she was shrugging it off her shoulders, Mr. Magnusson stepped closer. Several things cluttered her mind at once: That he smelled of laundry starch. That the gold bar connecting his collar points beneath the striped knot of his necktie was engraved with tiny nautical compasses. And that she was almost positive he was looking down her dress.

That realization did something strange to her stomach. She knew she wasn’t unattractive—at least, she didn’t think so. Not anymore. When she was a child, she was teased about her heavily freckled skin. Even now, most men only looked at her with mild interest before setting their sights on other women with flawless complexions. But every once in a while she ran across a man who actually liked freckles.

Maybe Winter was one of them.

Did he see her as a sideshow curiosity, or something more? Perhaps he was merely a man, and breasts were breasts were breasts. She held up her coat between them. “How’s the view from up there?”

“Not as clear as your view of me the other night.”

“To be fair, I don’t believe that could’ve been any clearer.”

He plucked the coat from her fingers. “You sure didn’t act like you minded.”

“I didn’t.” She meant that to be a question, but it came out wrong. Winter seemed as surprised by it as she was, but he didn’t comment. Surely he was aware how nicely his body was put together; he probably heard it all the time. He hung up her coat, then, without touching, extended his hand behind her back, urging her to accompany him farther into the study.

They skirted around a bank of standing bookshelves in the middle of the room and came face-to-face with the head of a dragon—or the neck and head of one, to be exact. Openmouthed and baring sharp teeth, the wooden carving was about her height, on display in a glass case.

“That’s Drake,” Winter said, stuffing his hands in his pockets. “The bow off a Viking longship from the twelfth century.”

“You are Scandinavian, then?”

“Swedish. My parents immigrated here when my mother was pregnant with me.”

“An arduous journey for a pregnant woman.”

Something in his brow shifted. A wistfulness. Or guilt, perhaps. “She insisted on coming to give me a better life. My siblings were born here.”

She walked around the dragon, peering through the glass. The carving was crude, the wood cracked and splintered. “Shouldn’t this be in a museum?”

“Probably. If we ever need money, we can sell him. He’s worth more than the whole damn house. It was one of the first things my father had imported after the bootlegging money started flowing. I’ve got an uncle who’s an archaeologist. My younger brother is on a dig with him out in Cairo right now.”

“Really? How exciting. Hope he’s not opening up any cursed tombs.”

“My brother could fall into shit and come out smelling of roses.”

Aida laughed.

In a fluid pair of movements, Winter curved his body closer to hers while settling his forearm above his head on the top of the glass case. His fingers tapped on the glass. A big body like his possessed an unspoken dominance if the personality commanding it understood its power, and Winter did. He towered over her at an angle that forced her to tilt her face up and back to meet his gaze, and spoke in a lower, more relaxed tone, as if he were sharing a choice bit of gossip, luring her into his web. “Uncle Jakob found the dragon bow a few years ago. Found three, actually—reported one, kept one for himself, and gave my father Drake, here.”

“Lawbreaking runs in the family.”

He made a grunting noise. “My uncle is fond of shipping black market goods, and my father always had boats. That’s why he got into bootlegging in the first place.”

“Bo mentioned that your father was a fisherman.”

“Crab and salmon, mainly. I’ve traded most of the fishing fleet for rumrunners and a couple of big, new powerboats that go to Canada. But I haven’t gotten rid of the crabbers.”

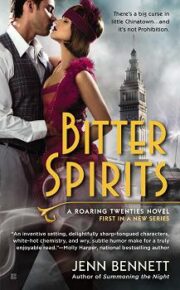

"Bitter Spirits" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bitter Spirits". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bitter Spirits" друзьям в соцсетях.