Winter shook the umbrella outside the door as Aida looked around. The apothecary shop’s walls were wrapped in wooden shelves that stretched to the ceiling, each of them brimming with ceramic jars lined up in neat rows. Tracks of wooden drawers stood behind a long counter to one side. Near the back of the shop, sticks of pungent sandalwood incense smoked from a brass bowl filled with sand.

The shop was empty until a thin, elderly man appeared from a dark doorway. “Good afternoon,” he said with a British accent as he shuffled around the counter to greet them. He was shorter than Aida, with salt-and-pepper hair braided into a queue that hung down his back. And though he was dressed in western clothes—black trousers, white shirt, gold vest—he was wearing a pair of Chinese black silk slippers embroidered with honeybees.

“Hello,” Aida said. “We are looking for Doctor Yip.”

“You have found him.”

When Winter turned to face him, Yip froze. Aida tensed herself, hoping the elderly man hadn’t recognized Winter as a gangster; Winter had said this street was on the edge of a tong leader’s territory. But before she could worry any further, Yip exhaled. “Forgive me, but I do believe you are a very large man.” He grinned, laughing at himself, then nodded at Aida. “Quite wise to have a protector like this when walking some of these streets, young lady.”

She introduced the two of them and the herbalist heartily shook their hands before ushering them farther into the shop. “How can I help you?”

“My landlady sent me here.”

“Oh? Who might that be?”

“Mrs. Lin. She owns the Golden Lotus restaurant on the northern end of Grant.”

“Ah yes. Mrs. Lin—always brings me cookies, trying to fatten me up.”

Aida smiled. “Yes, that’s her. She said you might be able to help us.”

He stepped behind the counter and faced them. “I can try. What do you need? A remedy?”

“Information,” Winter said as he propped up the closed umbrella and removed his gloves.

“About . . . ?”

“Black magic.”

“Black magic,” Doctor Yip repeated, drawing out the words dramatically. “Sorcery? Spells and things? Can’t say I know much, I’m afraid. I’m a healer, not a sorcerer.”

“We don’t need a spell,” Aida clarified. “Something’s been done already. We’re wanting to know how to stop it.”

Curious eyes blinked at Aida. “What kind of something?”

Aida said what she’d rehearsed with Winter on the walk. “We have a friend who’s been cursed. A sorcerer used a spell to open his eyes to the spiritual world—ghosts and things of that nature. And now he’s being haunted by ghosts that have been manipulated by magic.”

“Oh my,” the herbalist said. “Very interesting.”

“Do you believe me, or do you think I’m crazy?” Aida asked with a half smile.

“Strange things happen every day. If you say it’s true, I believe as much as I can without having witnessed it myself. I’ve felt things that I couldn’t explain. I am a Shenist. Do you know what that means?”

Aida nodded. “Mrs. Lin says it’s the old Chinese religion.”

“Most religions are old,” he said with kind smile. “I believe in shens—celestial deities made of spirit. I also believe in lower spirits, other than the ones I worship—what you would call ghosts. It is not a stretch to think that someone could manipulate a spirit of the dead. Though I wouldn’t know how, exactly.”

“Four Chinese coins were found on the person being haunted,” Winter said. “We’ve been told that’s considered unlucky?”

Doctor Yin crossed his arms over his black and gold vest. “Four is very unlucky. In Cantonese, the word for ‘four’ sounds like the word for ‘death.’ In Hong Kong, many buildings do not have fourth floors—or fourteenth, or twenty-fourth. People are careful to avoid the number four on holidays and celebrations, like weddings, or when family members are sick. Westerners call this tetraphobia. But four Chinese coins, you say?”

“Yes. Old gold ones.” Winter described them briefly.

“There is an old folk magic belief that if you leave four coins on someone’s doorstep with ill intent, you curse the home’s owner. I’ve heard stories of businessmen in Hong Kong leaving four coins under the mat of a rival’s shop to give them bad luck and steal their customers.”

“What about in regards to a spirit or a haunting?”

He shook his head. “Sorry, that I don’t know.”

Winter groaned softly.

“But . . .” Yip added. “Someone else might. One of my customers has told me about a man who reads fortunes at a local temple—what used to be called a joss house.”

“Yes, I’m familiar with those,” Winter said.

“My customer, she says rumors are that this man knows more than fortune-telling. That he’s also a skilled sorcerer.”

Aida glanced at Winter, then asked Yip, “Can you tell us where the temple is and what the fortune-teller’s name is?”

“I don’t know which temple, sorry.”

“How many temples are there in San Francisco?” she asked.

Winter grunted. “Dozens.”

“He’s right, unfortunately,” the herbalist said. “If my customer returns, I can ask for the exact temple. I doubt the name of the man is known to her, but the moniker he uses for fortune-telling is Black Star.”

TEN

AIDA FELT WHAT SHE IMAGINED HER SHOW PATRONS DID WHEN their lottery ticket number was called: excitement, disbelief, and the thrill of a small victory won. As Doctor Yip waxed poetic about Shenist and Taoist temples in Hong Kong, she half listened while exchanging looks with Winter. Doubt began creeping in. It seemed too simple. Too easy. But how many Chinese sorcerers called themselves Black Star?

Maybe it was that easy. They thanked the herbalist profusely and Winter offered to pay him for the information.

“No, no,” Yip said, waving his hands in dissent at the generous bill that Winter held out in offering. “It is nothing. Not a well-kept secret or trained knowledge. Just gossip.”

“I insist,” Winter said.

“How about an exchange for services? If you’d like to get rid of that pain you’re carrying, I’d be happy to provide some relief.”

Winter stared blankly at him.

“The arm,” Yip said, pointing. “I can see how you’re holding it that it’s causing you discomfort. If it’s an injury, I can make the pain go away and speed the healing. Bring healthy blood flow to the right spots.”

“I don’t think so. No offense, but I’ve had some bad experiences with folk remedies recently.”

“Not a remedy. Acupuncture.”

“Needles?” Aida said.

Winter frowned. “Oh, no-no-no.”

“Doesn’t hurt. Doesn’t bleed. My needles are a fine quality, brought with me from Hong Kong. Very clean. Will only take seconds to place them, then you relax for a few minutes, and the pain will be gone. I have patients who come every week. Not just Chinese, but Westerners, too.”

“Oh, go ahead,” Aida encouraged Winter. “Why don’t you do it?”

Winter shook his head. “It’s kind of you to offer, Mr. Yip, but—”

“He’s afraid of needles,” Aida finished.

Winter narrowed his eyes down at her. “That’s not going to work.”

“Isn’t it?”

“Probably not.”

She laughed, and he grinned back at her. Flutter-flutter.

“I do it right back there,” Yip said, pointing to a long wooden bench and chair at the back of the shop.

“A needle seems much smaller than, I don’t know, let’s say, my lancet,” she said, grinning.

Winter sighed dramatically and slid his money across the counter. “Outmatched by a tiny woman.”

“Excellent!” Yip said. “Right this way.”

The herbalist questioned Winter about the state of his injury as they followed him to the bench at the back of the shop, where he shifted a carved wooden privacy screen and instructed Winter to remove his shirt while he disappeared in the back.

Aida glanced at Winter, and memories of Velma’s bathroom sprung into her mind. Well, what did she expect? The herbalist wasn’t going to poke needles through his shirtsleeves. Looked liked it was turning into her lucky day. She plunked down on a nearby chair and tried to act casual.

Winter set his fedora on the bench, then turned to her, shrugging out of his overcoat. “Hold this for me.” She took the heavy coat from him and folded it neatly on top of her lap.

“And this.” He stood inches away, towering over her with his suit jacket dangling in front of her face. She took it and folded it on his coat while eyeing the gun holstered at his ribs. After unbuckling the strap across his chest, he slid it off his good shoulder. “It can’t fire itself,” he assured her as he handed her the heavy leather holster. She made a face at him as she accepted it.

He proceeded to remove clothing until he was standing in nothing but his too-tight pants, suspenders dangling at his hips, and a sleeveless undershirt—which molded over every muscle in his broad chest and bared his tree-trunk arms. Her gaze flew to his injury.

“Good lord, Winter!”

Most of his left shoulder was mottled black and purple. She’d never seen an uglier bruise.

He tucked his chin to peer at his shoulder. “It’s not as bad as it looks.”

Yip came out of the back room rolling a metal cart. He stopped to inspect Winter. “Oh! Very nasty. It’s okay, though. I’ll help you. Sit.”

An array of slender silver needles lay fanned upon a white cloth on the herbalist’s cart. “The newest type of needle, stainless steel,” Yip said. “Sharp and clean.”

Winter eyed them warily. “It’s the sharp part I don’t like.”

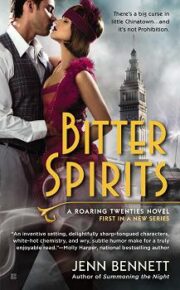

"Bitter Spirits" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bitter Spirits". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bitter Spirits" друзьям в соцсетях.