“Oh?”

“Don’t get too excited. It might not pan out, but it could be worth investigating. I have a map to show us how to get there.”

“That’s damned resourceful,” he said, sounding impressed.

“You hired me to help you.”

“Indeed I did. Bo should be back from an errand any minute. As soon as he arrives, we’ll head over there. Shall I meet you in an hour, say?”

Bo was coming, too? A pang of disappointment tightened her chest. “Sure. But I have to be at Gris-Gris around five. I’m doing an early show tonight for happy hour.”

“That’s fine. I’ll get you there in time.”

One of the girls who lived in the building clicked on the line and asked to use it.

“In an hour?” Aida said quickly.

“With bells on.”

She hung up and changed her clothes, dressing in a camel-colored skirt and a matching jacket. Casual, but smart. Very businesslike. It looked good with her tan stockings, which had pretty little scrolling shapes embroidered on the calves and hid the freckles on her legs. She finished getting ready, then headed downstairs in time to meet him.

Aida’s heart pounded wildly as she glanced toward the entrance and found him stepping inside the restaurant wearing a long black coat, black suit, and black necktie with red chevrons running down the middle peeking from his vest. Pausing near the door, he removed his hat and brushed away droplets of rain. Gray light filtered in from the windows behind him, where Chinese characters and the pronouncement “Best Almond Cookies in Chinatown” surrounded a painted lotus blossom.

His eyes found hers. “Miss Palmer,” he said politely, as if he were an upstanding gentleman and not a bootlegger. As if they were merely business acquaintances . . . which they were, she reminded herself. “Shall we?”

Dodging customers tottering up to the register, she followed Winter outside into the fresh air, heavy with the scent of wet pavement. She eyed rain dripping from a shallow ledge above the entrance. “Everyone told me it would be dry here in the summer.”

“Usually is.”

“Where’s Bo?” she asked in her best neutral tone as she pulled on a pair of short brown gloves with bell-shaped cuffs.

“He dropped me off.”

“Ah.” Flutter-flutter. She squelched her excitement and glanced around. The newsstand next door had erected a rainy-day tarp that tied to a street sign and a telephone pole. “Maybe we should grab a taxi.”

Winter snapped open a large black umbrella. “Nonsense. It’s barely raining. Come.” He shifted her under the umbrella and out of the entry so an elderly couple could step inside. His hand lingered on her back as they walked to a spot by the newsstand.

Hope and anxiety quickened her hummingbird pulse. Being close to him set her nerves dancing. She was close enough to catch his scent, crisp and clean, a touch of the orange oil that permeated his house. She glanced up and found him studying her. Had he seen her sniffing his coat like a dog? “Sorry. You smell nice.”

“Barbasol cream.” He was hiding a smile. Amused. Relaxed. Very non-businesslike.

Emboldened by his good mood, she teased him a little. “I thought it was eau de bootlegger.”

“No,” he answered with a soft chuckle, “that smells like money and sweat.”

He was joking with her—smiling and laughing and touching her. She was far happier than she probably should be about it. Any second, her feet would be floating over the sidewalk. She forced herself to settle down and dug out Mrs. Lin’s map. “Look at this and tell me if you know where it’s at.”

“All right. No need to be pushy,” he said with good humor. As rain dripped from the umbrella onto his coat sleeve, he studied the hand-drawn path through Chinatown’s labyrinth streets and noted where he’d make a bit of a detour. “A small tong leader has a warehouse here. We’re on decent terms—Bo and I have already ruled him out as a possible ringleader for all the ghost business—but I don’t want him to think I’m sniffing around without his permission.”

The thought hadn’t crossed her mind that it might be dangerous for a notorious bootlegger to be prowling Chinatown, whether or not it meant facing someone he suspected of his recent hauntings. He must’ve noticed the concern on her face, because he opened up his long overcoat and showed her a handgun strapped beneath his suit jacket. “Just in case. Don’t worry.”

“Don’t worry?” she repeated, looking around quickly to make sure no one else had seen it. “That makes me even more nervous. What if you have to use it?”

He curled gloved fingers around her chin and lifted her face. “Then the other guy’ll have a bullet in him and you’ll be safe. I promise you that.”

“I don’t like guns.”

He released her chin. “Then try to keep your hand out of my jacket and you’ll never know it’s there.” He gave her a quick wink that made her stomach flip, then, with a gentle hand on her shoulder, prodded her down the sidewalk.

Light drizzle darkened the pavement and carried scents of Chinatown: dried fish, exotic spices, old wood, and tobacco leaves from a nearby cigar warehouse. Across the street, tourists huddled under dark red canvas awnings to get out of the rain and browse ceramics and toys on display in wooden crates. Tin Lizzies and delivery trucks rumbled down the street, splashing through puddles collecting near the curbs.

“Bo said he started working for you when he was fourteen,” she said as they sauntered down Grant, passing a butcher’s window where a row of skinned ducks hung above signs in English and Chinese, promising the freshest meat for the best price.

“He was half your size back then,” he said. “Did he tell you how we met?”

“No.”

“I box at a club on the edge of Chinatown, a few blocks from my pier—”

“That explains a lot,” she mumbled, eyeing a thick arm. Half of him was getting wet, she noticed, as he was tilting the umbrella at an angle to account for their height difference and keep her dry.

He blinked at her with a dazed look on his face and nearly smiled. “Well,” he said, clearing his throat. “Bo lived with his uncle. To bolster the family income, he took to pickpocketing. Was good at it, too. Fast as a whip—you never knew he’d been in your coat. He robbed me blind when I was getting dressed for a match.”

“Oh dear.”

“After the match was over, I caught him in the alley behind the club. He was so small, I could lift him off the ground with one hand. Little degenerate looked me straight in the eye and told me, yes, he’d done it and wasn’t sorry one bit.” Winter smiled to himself. “I knew he was either brave or stupid, so I asked him to do a little spying here and there, paying him mostly in hot meals at the beginning. He can still eat his weight in lemon pie.”

Aida laughed.

“His uncle died a couple years later, on Bo’s sixteenth birthday. Bo called me because he couldn’t afford to bury the man.”

“How awful,” Aida said, feeling for her locket.

“Damn disgrace that the old man didn’t even leave Bo a penny.” His brow lowered, then he shrugged away the memory. “Bo’s been living with me ever since.”

“I thought he told me he moved in with you after the accident? Wasn’t that two years ago?”

“We both moved back to the family home then, yes.”

“From where? Mrs. Beecham mentioned an old house of yours . . .”

Winter stiffened. “She had no business bringing that up.”

“Oh, I didn’t know—”

“I’d rather not talk about it,” he said, cutting her off.

His gruff tone stung. She’d unintentionally touched a nerve, and for a moment the air between them was awkward and tense. Bo had warned her about prying into his past.

“No one’s told you about the accident?” he said after a long moment. “Not Velma?”

“No, but I gather both your parents died.”

The subject hung in the air for several steps. “I didn’t mean to bark at you. I just don’t like talking about it.”

“I can understand that. Everyone I’ve ever loved is dead.”

His hard look softened.

“Apart from that, people talk to me intimately about death all the time,” she said. “Everyone wants to be reassured that there’s life after death, but I always beg them not to forget that there’s life before death—and that’s the only thing we really have any sort of control over. Anyway, if you ever feel inclined, I’m a bit of a specialist in these matters, and you have hired my services.”

He grunted his amusement. “I suppose I have. And I appreciate that, but some things are best left in the past.”

“Now that I agree with,” she said with a soft smile.

It took them a quarter of an hour to make it to the first side street. Avoiding the subject of the accident, they talked the entire way, first about Chinatown, then about what she remembered of the city from her childhood. The smell of fish cooking got them chatting about the Magnusson fishing business and crab season, then he told her a few stories from his childhood—stealing away from school at lunchtime to smoke cigarettes behind the baseball field . . . absconding with one of his father’s fish delivery trucks to meet schoolmates at Golden Gate Park.

Once they’d turned down the side street, the scenery began changing. Gold-painted window frames, pagodas, and curling eaves all but disappeared. Forgotten laundry dripped from balconies, and the smell of sewage wafted from dark corners. By the time they’d taken two more turns, they were sloshing through puddles on narrow backstreets where the asphalt gave way to old paving stones.

They found Doctor Yip’s storefront halfway down a cul-de-sac, right where Mrs. Lin said it would be. The sign was in Chinese, but they spotted the landmark she’d mentioned, a metal yellow lantern that hung near a door under an arch of honeycomb cutout woodwork. A string of bells tinkled when they walked inside.

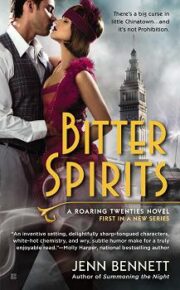

"Bitter Spirits" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bitter Spirits". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bitter Spirits" друзьям в соцсетях.