Aida smiled tightly as the woman embraced her shoulders and kissed her cheeks, engulfing her in brandy and perfume. “Thank you for having me.”

“Nonsense. You’re the talk of the party,” Mrs. Beecham said with a laugh, waving her cigarette holder, scattering ashes around. Goodness, the woman was drunk. She was also Aida’s age, if not younger—certainly not the doddering, lonely widow Aida had expected.

“Your home is lovely, Mrs. Beecham,” she said as the piano player finished and the party began shuffling past them into another room.

“Call me Florie. Everyone does. And isn’t it marvelous?” Not one single strand of her slicked platinum bob shifted out of place when she tilted her head back to admire her own decor. “I moved in three weeks ago. This is my first party.”

“How nice.”

“I see you’ve found Win. Don’t mind his brutish manner; that’s just a facade. He gave me the idea to hire you. He said, ‘Florie, old gal, there’s this spiritualist down at one of the black-and-tans who’d make your party more interesting.’ And it was a brilliant idea, as usual. All his ideas are brilliant.”

Aida flicked a questioning glance at Winter. His look was something between sheepish and apologetic.

Mrs. Beecham teetered past Aida to sling both her arms around one of Winter’s, hanging on to it like the remaining mast on the Titanic. He extracted her cigarette holder half a second before it burned a hole in his tuxedo sleeve and set it on a nearby hall table.

“Win and I went to Berkeley together. Before he got the boot.” Mrs. Beecham kicked a leg out and nearly tripped over her gown.

Winter pulled the woman to the side and steadied her as guests filed past them into the parlor. “I think you better slow down on those sidecars.”

“Says the big rumrunner!”

Aida eyed the woman’s perfect pale skin and dimpled smile. An unwelcome tightness squeezed her lungs. She glanced at Winter. “I don’t believe I’ve heard the story of you and Berkeley.” Did her voice sound strained? She steeled her posture, hoping that would help.

“Oh, it’s a good one,” Mrs. Beecham confirmed. “Win can tell you the long version, but the short of it is—”

“Florie,” Winter said tiredly.

“Shhh. Lemme tell. See, we had this friend, Nolan, who edited a university literary journal, and he printed a D. H. Lawrence review that was a bit . . . risqué, and even though he left blanks for the offensive words, the university was furious and he got expelled. Then Win here”—Mrs. Beecham poked Winter square in the chest—“wrote a scathing treatise against censorship, only he didn’t include blanks for the offensive words, and there were a lot of them. He had it printed up as a handbill and circulated it around campus. The best part is that he included an unflattering caricature of the dean who fought for Nolan’s expulsion—miserable old hag. The drawing was in the buff, if you know what I mean.”

Aida cocked a brow at Winter.

“I didn’t sketch it myself,” he said, almost sheepish.

“Ugh,” Mrs. Beecham complained. “One of the art students drew it—a horrible caricature with great sagging breasts. It burned my eyes. Anyway, someone ratted on Winter and he got kicked out. It was terribly boring after he left.”

“I’ll bet,” Aida murmured.

Mrs. Beecham laughed. “The funny part is that he was only one semester away from graduating.”

“That’s not funny,” Aida said, suddenly annoyed. “That’s terrible. Why didn’t you go somewhere else and finish?”

“Why bother?” the woman answered for him. “Volstead passed and his father traded in the fishing for bootlegging. Pays better than building boat engines and chasing down salmon.”

Winter grunted.

“Can you believe that was what—seven, eight years ago? Time flies,” she said with a dramatic shrug. “It’s been such a blur since college, my whirlwind romance with Mr. Beecham, his unexpected death. It’s been trying.”

“I can feel your pain inside the walls of this lavish shanty,” Winter mumbled.

“It does help to soothe my frail nerves.”

“Is gold the new mourning color?” Winter said, looking at her dress.

“I put one of his hideous paintings in the parlor as a tribute. That means more than a boring black dress.” She gestured into the dark parlor, where candles were burning and wooden chairs had been set in rows in front of a round table draped in patchwork Romany cloth. Behind it was a garish bohemian painting of what was clearly Mrs. Beecham lying half naked in a field of flowers. Her nipples were painted a shade of blindingly bright pink and her face was blue.

“Maybe you should’ve married someone who wasn’t three times your age,” Winter said.

“He was sweet to me, once. But perhaps you’re right. Really, Win, just think if you would’ve stayed at Berkeley—the two of us might’ve been married and I could be decorating your house right now.”

“I like my house just fine as is.”

“I mean your old house, not your father’s. Never mind. Let’s not dig up bad memories.”

What in the world was she talking about? Aida’s head was spinning from all the information this obnoxious woman was unleashing. Every word that came out of her mouth made Aida loathe her more and more.

“Regardless, it all turned out fine anyway. I rather like being a widow. I can do anything I want, with whomever I want, and nobody can say a damn thing about it.” Mrs. Beecham turned her face up to Winter and grinned like a harpy while her fingers danced up his arm suggestively.

Were they lovers? Was this what he preferred in a woman? Perhaps that protective show with Mr. Morran was just everyday business for someone like him. Maybe he would’ve done that for any girl standing in her place.

Something snapped inside her. She had her pride, and she’d made a promise to herself that she would take no job she didn’t want, and Sam would’ve encouraged her to stick to that promise. “I’m sorry, but I’ve changed my mind. I think this party will do just fine without me,” Aida said to Mrs. Beecham. “I appreciate your offer, but perhaps your guests would prefer music over mysticism.”

“Aida,” Winter said, unhooking Mrs. Beecham’s arm as he started toward her.

“Come on, darling,” Mrs. Beecham said to Aida, as if she were a small child who needed to be coddled. “Don’t be that way. Win and I are old friends. Have a drink.”

“I don’t want a drink.”

The widow waved a hand toward the parlor. “Well, let’s get started then.”

“I said I’m not doing it, and that’s final.”

“Stop being silly.”

“Oh, for God’s sake, shut up, Florie,” Winter snapped.

Conversation and laugher inside the parlor halted as people turned in their seats to stare.

“Don’t you get crude with me in my house,” the widow said to Winter, then pointed at Aida. “I’m paying you for a séance, so get inside that room and do your job.”

A thousand emotions crackled inside Aida. She had wild thoughts of taking Mrs. Beecham’s cigarette holder and shoving it inside the woman’s ear. “You want a séance?” she said through gritted teeth. “I’ll give you a séance.”

Aida stormed to the back of the parlor, ignoring the mumbles and whispers. She stopped at the gypsy table and removed her trusty silver lancet from her handbag, unscrewing a cap on the end to bare a small blade. The garish painting of Mrs. Beecham hung on the wall a couple of feet away. “What was your husband’s name?” she shouted back at the widow.

“What?”

“His first name.”

“I don’t want to participate. This is for my guests. Andy, you go first. Where’s the violinist? We can’t start un—”

Aida squinted at the corner of the painting. “Harold Beecham.”

“Oh, yes, well. I’d rather you didn’t—Andy?” Mrs. Beecham called desperately. “Where are you? It’s so dark in here. There aren’t enough candles.”

“Over here, Florie. I’m coming.” A brown-haired man sidestepped behind a few chairs to stand next to her.

Aida ignored them. With one hand on the painting, she took a deep breath and pricked her thigh with the lancet blade. Tears stung her eyes as endorphins reared up. Using the pain to enter a winking, oh-so-brief trance state, she reached out into the void, calling for Mrs. Beecham’s husband.

Her vision wavered. She inhaled sharply, feeling a silent answer to her call. The spirit came rushing toward her over the veil like a demon released from the pit of hell.

EIGHT

WINTER HALTED IN THE MIDDLE OF THE PARLOR WHEN AIDA’S breath turned visible, barely hearing the gasps of surprise around him. He wasn’t unsettled by the puffs of white billowing from her mouth—not anymore. He was more interested in the silver instrument she had in her hand.

Aida’s body stiffened, then her face became animated. Her head swiveled around in all directions until she found Florie. “Sweetheart,” she said. “I never thought I’d lay eyes on you again.”

Florie froze, then backed up as Aida stalked her around the rows of chairs.

“Aren’t you glad to see me?” Aida’s voice said. “I remember your last words like it was yesterday . . . when I found you riding the Halstead boy like a prized pony at the county fair.”

Florie paled, then laughed nervously. Her eyes flicked to her apparent lover, Andy Halstead, who stood next to her looking as if he were going to faint and keel over.

Aida walked faster. “When my heart failed, you didn’t even try to save me. You just said, ‘Looks like we killed him.’”

Florie’s back hit the wall. She yelped. Aida lunged with outstretched arms. Something flew from her fingers and sailed through air, dinging against the wall, but she didn’t seem to notice. She was too busy grasping Florie’s throat with both hands as she wrestled his college friend to the floor. Winter raced toward them, knocking chairs out of the way while party guests stood by in a drunken daze.

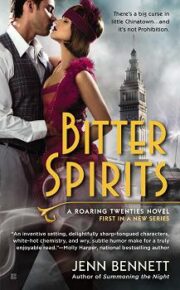

"Bitter Spirits" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bitter Spirits". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bitter Spirits" друзьям в соцсетях.