Glenkirk and his family were astounded, even openly awed, by the elegant magnificence of the Louvre palace. There was absolutely nothing like it in England. They were met by the two royal English ambassadors, the earl of Carlisle and Viscount Kensington, who quickly escorted them to King Louis's chamber where the signing would take place. First, however, the proper protocol had to be followed. The two ambassadors handed the contract to the king and his lord chancellor to read. This done, the king signified his acceptance of the terms previously agreed upon, and only then was the princess summoned to her brother's presence.

Henrietta-Marie arrived, escorted by the queen mother, Marie di Medici, and the ladies of the court. The princess was garbed in a gown of cloth-of-gold and silver, embroidered all over with golden fleurs-de-lys, and encrusted with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires. Once the bride had taken her place, the bridegroom's proxy was called. The due de Chevreuse came into the king's chamber wearing a black-striped suit covered with diamonds. He bowed first to the king and then the princess. Then the due presented his letter of authority to the king, bowing once again. Accepting it, Louis XIII handed it to the chancellor, and then signed the marriage contract. Other signatories were Henrietta-Marie, Marie di Medici, the French queen, Anne of Austria, the due de Chevreuse, and the two English ambassadors.

The contract duly signed and witnessed, the formal religious betrothal was performed in the king's chambers by the princess's godfather, Cardinal de la Rochefoucauld, the due de Chevreuse answering for the king of England. The ceremony over, the princess retired to the Carmelite convent in Faubourg St. Jacques to rest and pray until her wedding on the first of May, and the guests departed, the duke of Glenkirk and his family returning to Chateau St. Laurent.

On Henry Lindley's sixteenth birthday, which happened to be the thirtieth of April, the Glenkirk party, the St. Laurents, and Lady Stewart-Hepburn traveled to Paris for the royal wedding. It was better, the due said, to go the day before rather than waiting until the first, but the roads were clogged anyway with all the traffic making its way into the city for the celebration. By chance, James's brother-in-law had a small house on the same tiny street as did Jasmine's French relations, who would not be coming for the wedding. The de Savilles lived in the Loire region, many miles from Paris, and while of noble stock, they were not important. Besides, it was springtime, and their famous vineyards at Archambault needed tending more than they needed to be in the capital for the princess's wedding to the English king, so they gladly loaned their little house to their relations.

The wedding day dawned gray and cloudy. By ten o'clock in the morning it was raining. Nonetheless, crowds had begun gathering outside of the great square before Notre-Dame the previous evening. Now the square was overflowing with people eager to see the wedding. The archbishop of Paris had gotten into a terrible row with the Cardinal de la Rochefoucauld. It was the cardinal who had been chosen to perform the wedding ceremony, despite the fact that the cathedral was the archbishop's province. The royal family had brushed aside the archbishop's protests as if he had been no more than a bothersome insect. Furious, the archbishop had retired to his country estates, not to return until after the wedding. He could not, however aggravated he might be, deny the princess the use of his palace, which was close by the cathedral, and so at two o'clock that afternoon in the pouring rain, Henrietta-Marie departed her apartments in the Louvre for the archbishop's residence in order to dress.

Fortunately a special gallery had been constructed from the door of the archbishop's palace to the door of the cathedral. It was raised eight feet above the square and set upon pillars, the lower half of which were wrapped in waxed cloth, and the upper half in purple satin embroidered with gold fleurs-de-lys. At the west door of the cathedral was a raised platform which was sheltered by a canopy of cloth-of-gold that had been waxed to prevent the rain from penetrating it. At six o'clock in the evening, the bridal procession began streaming out of the archbishop's palace, moving down the open-sided gallery toward the cathedral.

The bridal party was led by one hundred of the king's Swiss Guards. The first two rows were a mixture of drummers and soldiers with blue and gold flags. Following the guards came a party of musicians. Twelve played upon oboes. There were eight drummers who were followed by the ten state trumpeters playing a fanfare. Following the royal musicians was the grand master of ceremonies behind whom strode knights of the Order of the Holy Ghost in jeweled capes. Next came seven royal heralds in crimson-and-gold-striped tabards.

The bridegroom's representative, the due de Chevreuse, was proceeded by three ranking noblemen. He was garbed in a black velvet suit, slashed to show its cloth-of-gold lining. On his head was a velvet cap sporting a magnificent diamond that glittered despite the dullness of the late afternoon. Behind him were the earl of Carlisle and Viscount Kensington in suits of cloth-of-silver.

The populace standing in the pouring rain on either side of the gallery struggled against each other, attempting to get the best glimpse of the wedding party and the court. Cries of "God bless the king" and "Good fortune to the princess" were heard by those moving along the gallery toward the platform and the cathedral. Most of the guests would pass through the raised, canopied flooring, and take their places within the cathedral. Only certain chosen ones would remain upon the dais to see the ceremony performed. Because the king of England was considered a Protestant, it was necessary to perform the wedding ceremony before the doors of the cathedral, but as all weddings had once been performed in this manner, little was thought of the arrangement. Afterward, a mass would be celebrated within Notre-Dame.

Among the chosen to view the wedding, India Lindley stood shivering as she drew her cloak about her. She should have worn her rabbit-lined cape, but it was not nearly as fashionable as the one she was wearing. She looked at the French courtiers in their magnificent clothing. She had never seen anything like it. It was utterly spectacular, and she felt like someone's poor country relation. Her mother, of course, had fabulous jewelry which covered a multitude of fashion sins, but she and Fortune looked positively dowdy even in comparison to the bosomless eleven-year-old Catherine-Marie St. Laurent, whose claret-colored silk and cloth-of-gold gown was delicious.

"Here comes the bride," Fortune singsonged next to her. Fortune was enjoying every moment of this colorful and marvelous show. It didn't matter to her that her mother and sister looked like a pair of burgher's daughters.

India focused her eyes upon Henrietta-Marie, who was escorted by both of her brothers, King Louis XIII, resplendent in cloth-of-gold and silver, and Prince Gaston, elegant in sky blue silk and cloth-of-gold. The petite sixteen-year-old bride was dressed in an incredible gown of heavy cream-colored silk embroidered all over with gold fleurs-de-lys, pearls, and diamonds. The dress was so encrusted with gold and diamonds that it glittered as she walked. On her dark hair was a delicate gold-filigreed crown, from whose center spire dripped a huge pearl pendant that caused the watching crowds to gasp.

"I have better," murmured the duchess of Glenkirk, and her mother-in-law restrained her laughter.

Behind the bride and her brothers came the queen mother, Marie di Medici, wearing, as always, her black widow's garb, but dripping with diamonds in recognition of the occasion. Finally came France's queen, Anne of Austria, in a gown of cloth-of-silver and gold tissue, sewn all over with sapphires and pearls, leading the French court. The few English guests had already been brought to the raised and canopied dais to await the arrival of the bridal party now come.

The cardinal performed the wedding ceremony, and then the bride, her family, and the French court were escorted into the cathedral for the celebration of the Mass. Inside, the cathedral was filled with other invited guests: members of the parliament, other politicians, and civic officials, garbed formally for this occasion in ermine-trimmed crimson velvet robes. The walls of the cathedral were hung with fine tapestries, and the bridal party was seated upon another canopied, raised dais. Having settled the bride upon a small throne, the due de Chevreuse departed her side to escort the two English ambassadors and the few English guests to the archbishop's palace for they would not attend the Mass.

"Ridiculous!" Jasmine muttered beneath her breath.

"Be silent!" James Leslie said softly, but sharply. While he agreed with his wife that this prejudice between Roman and Anglican, Anglican and Protestant, was absurd, it was a fact they had to live with, and to involve one's self in the sectarian fray was to make enemies. It was better to remain neutral. Lady Stewart-Hepburn nodded her approval of her son's wisdom.

"Did you see the gowns?" India said excitedly to her mother. "I have never seen such clothing!"

"A bridal gown should be beautiful," Jasmine replied.

"Nay, not the bridal gown," India responded. "It is lovely, of course, but it is the gowns worn by the women of the French court that I am envious of, Mama. Your jewels, naturally, always overshadow anything you may wear, but Fortune and I look like two little sparrows compared to the French ladies. Why, even flat-chested Catherine-Marie outshines us. It is most embarrassing! We are here to represent our king, and we look like two serving wenches!"

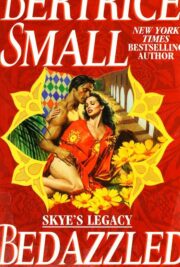

"Bedazzled" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bedazzled". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bedazzled" друзьям в соцсетях.