“Pauline…”

She whipped around. “Yes,” she said. “Jenna left it on the table at the restaurant last night and I picked it up.” She widened her brown eyes at him. When they’d first met, her eyes had reminded Doug of chocolate candy. “I rescued the Notebook. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’d like to take a shower. In peace.”

“No,” Doug said. “I will not excuse you. Why didn’t you give it back to Jenna? What is it doing here?”

“She was in a hurry, remember? She and Stuart raced away in that cab.”

What Doug remembered was standing out on Greenwich Avenue trying to hail Jenna and Stuart a cab, but having no luck. That far downtown, cabs were impossible to find. What Doug remembered was considering asking the maître d’ to call a car service for the kids, but then at the last moment a cab appeared, and Jenna and Stuart hopped in it. But there had been a full ten minutes, maybe longer, with the four of them outside on the sidewalk. And Pauline had had the Notebook; she had probably stuffed it into one of the enormous purses she liked to carry.

“She wasn’t in a hurry,” Doug said. “We waited around for goddamned ever for that cab. I’m not wrong about that, am I?”

“I forgot to give it back to her,” Pauline said. “I meant to, but then we were so caught up in trying to get them a cab, I forgot.”

“You forgot?” Doug said.

“Yes.”

“Really?”

Pauline nodded once, with conviction. That was her story and she was sticking to it. As Arthur Tonelli’s bathroom filled with steam, Doug realized something. He realized that he did not love Pauline. It was possible that he had never loved Pauline. On Monday, once the wedding was over and they were safely back home, he was going to ask Pauline for a divorce.

He turned and walked out. It felt good to have made that decision.

Pauline must have sensed something dire because she shut off the water, wrapped herself in a towel, and followed him out.

“I need you to believe me,” she said.

Doug watched her clutch the towel to her chest. Her thick, dark hair, out of its ponytail, fell in damp ropes over her shoulders.

“I do believe you,” he said.

“You do?”

“Yes,” he said. “You’ve presented a plausible argument. Jenna left behind the Notebook, you wisely scooped it up, and amidst all the brouhaha of trying to flag a taxi, you forgot to return it to her.”

Pauline exhaled. “Yes.”

“My question now is, did you read it?”

As Pauline stared at him, he watched conflicting emotions cross her face. He was an attorney; he dealt every day with people who wanted to lie to him.

“Yes,” she admitted. “I read it.”

“You read it.” He had no reason to be surprised, but he was anyway.

“It was driving me crazy,” Pauline said. “The Notebook this, the Notebook that, what ‘Mom’ wrote in the Notebook. Your daughters-and you, too, Douglas-treated the thing like the fifth gospel. Jenna wouldn’t accept one suggestion-not one-from me. She only wanted to follow what was in the goddamned Notebook. And I wanted to see exactly what that was. I wanted to see what Beth had to say.”

Doug didn’t like hearing his second wife speak his first wife’s name. This had always been true.

“So you read it?” Doug said. “You read it today? While I was at work?”

“Yes,” Pauline said. “And I have to say, Beth covered all the bases. She let Jenna know exactly what she wanted-down to the pattern of the silver, down to the song you and Jenna should dance to, down to the earrings Jenna should wear with ‘the dress.’ It was the most blatant exercise in mind control I have ever seen. Beth planned her own wedding. She didn’t leave anything for Jenna to decide.”

Doug wondered if Pauline had read the last page. He wondered what the last page said.

“I think those were meant to be suggestions,” Doug said, feeling defensive.

“Suggestions?” Pauline said. “Beth flat-out told Jenna what to do.”

“Jenna is a strong person,” Doug said. “If she had disagreed with something Beth wrote, she would have changed it.”

“And go against the wishes of her dead mother?” Pauline said. “Never.”

“Hey now,” Doug said. “That’s out of line.”

“I offered to take Jenna out to try on wedding dresses,” Pauline said. “To try them on, that was all, to see what else was out there, to see if there was anything that suited her better than Beth’s dress-and she wouldn’t go. She wouldn’t even try.”

“I’m sure she looks lovely in Beth’s dress,” Doug said.

“You know,” Pauline said, “I thought it was a good thing that you were widowed instead of divorced. I was glad there wasn’t an ex-wife I had to see at family functions or that you were paying alimony to. But guess what? Beth is more intrusive than any ex-wife could have been.”

“Intrusive?” Doug said. “Define intrusive.”

“She’s everywhere. Especially with this wedding. She is a palpable presence in the room. She is an untouchable standard by which the rest of us have to be judged. She has taken on sainthood. Saint Beth, the dead mother, whose memory grows more burnished every day.”

“Enough,” Doug said.

“I just can’t compete,” Pauline said. “I’ll never come first, not with the kids, not with you. You are, all of you Carmichaels, obsessed with her.”

Doug thought that hearing such words might anger him, but he merely found them validating. “Listen,” he said. “I don’t think you should come to Nantucket this weekend.”

“What?” Pauline said.

“I guess what I’m really trying to say is that I don’t want you to come to Nantucket this weekend. It’s my daughter’s wedding, and I think it would be best if I went alone.” Doug heard Pauline inhale, but he didn’t wait around for what she was going to say. He left the bedroom, shutting the door behind him.

Down the stairs, through the kitchen. His cell phone was on the counter. He snatched it up and saw the two meager lamb chops sitting in a pool of bloody juices.

He wasn’t going to eat them. He was going out for pizza.

THE NOTEBOOK, PAGE 6

The Wedding Party

I assume you will ask Margot to be your Matron of Honor. The two of you have such a close relationship, and whereas at times I worried about the large age gap between you and the older three, I think that in Margot’s case, it was for the best. She was your sister, yes, but she was also a surrogate mother at times, or something between a sister and a mother, whatever that role might be called. Remember how she did your makeup for the ninth-grade dance? You wanted green eye shadow and she gave you green eye shadow, somehow making it look pretty good. And remember how she drove you down to William & Mary your sophomore year so that Daddy and I could celebrate our thirtieth anniversary on Nantucket? Margot is the most capable woman you or I will ever know. And to butcher the old song: Anything I can do, she can do better.

I assume you will also ask Finn. The two of you have been inseparable since birth. I used to call you my “twins.” Not sure that Mary Lou Sullivan appreciated that, but the two of you were adorable together. The matching French braids, the playground rhymes you used to sing with the hand clapping. Miss Mary Mac Mac Mac, all dressed in black, black, black.

As far as your brothers are concerned, I would ask Kevin to do a reading, and ask Nick to serve as an usher, assuming your Intelligent, Sensitive Groom-to-Be doesn’t have nine brothers or sixteen guys who served in his platoon who can’t be ignored. Kevin has that wonderful orator’s voice. I swear he is the spiritual descendant of Lincoln or Daniel Webster. And Nick will charm all the ladies as he escorts them to their seats. Obviously.

The other person who would be terrific as an usher is Drum Sr. Of course if Margot is your Matron of Honor, she might need Drum to watch the boys.

And then there’s your father, but we’ll talk about him later.

MARGOT

It felt so good to be back in the house of her childhood summers that Margot forgot about everything else for a minute.

The house was two and a half blocks off Main Street, on the side of Orange Street that overlooked the harbor. It had been bought by Margot’s great-great-great-grandfather in 1873, only twenty-seven years after the Great Fire destroyed most of downtown. The house had five bedrooms, plus an attic that Margot’s grandparents had filled with four sets of bunk beds and one lazy ceiling fan. It was shambling now, although in its heyday it had been quite grand. There were still certain antiques around-an apothecary chest with thirty-six tiny drawers, grandfather and grandmother clocks that announced the hour in unison, gilded mirrors, Eastlake twin beds and a matching dresser in the boys’ bedroom upstairs-and there were fine rugs, all of them now faded by the sun and each permanently embedded with twenty pounds of sand. There was a formal dining room with a table seating sixteen where no one ever ate, although Margot remembered doing decoupage projects with her grandmother at that table on rainy days. One year, Nick and Kevin found turtles at Miacomet Pond and decided the turtles should race the length of the table. Margot remembered one of the turtles veering off the side of the table and crashing to the ground, where it lay upside down, its feet pedaling desperately through the air.

In the kitchen hung a set of four original Roy Bailey paintings that might have been valuable, but they were coated in bacon grease and splattered oil from their father’s famous cornmeal onion rings. At one point, Margot’s mother had said, “Yes, this was a lovely house until we got a hold of it. Now it is merely a useful house, and a well-loved house.”

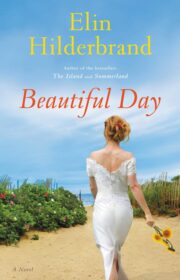

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.