Doug lay down on the bed, still in his shirt and tie and suit pants and Gucci loafers. He was suddenly tired. He and Pauline would be rising at 3 a.m. to make his 10:30 a.m. tee time at Sankaty; the mere thought was exhausting. Plus, Pauline set the air conditioner lower in the bedroom the way he liked it; the cool room was begging him to nap.

What was the Notebook doing there?

Jenna had brought it to dinner at Locanda Verde. Doug remembered her setting it on the table next to the platter of crostini with house-made herbed ricotta. He remembered Jenna saying, “There’s a cheat sheet in here, Daddy, an index card with the names of all of Mom’s cousins and their spouses and children. I memorized it, and you should, too.”

“Sure,” Doug had said automatically. He then wondered what it would be like to see Beth’s cousins, people he hadn’t seen since the funeral. He was grateful when conversation turned to another topic.

If the wine had gone to her head, Jenna might have left the Notebook at the restaurant. But she hadn’t left it at the restaurant. It had ended up here.

How, though? He certainly hadn’t carried it out.

So there was only one answer: Pauline had taken the Notebook and brought it home. However, Doug didn’t remember Jenna offering to show the Notebook to Pauline, nor did he remember Pauline asking to see the Notebook. If that had happened, he would have remembered. Pauline was jealous of the Notebook, which really meant that Pauline was jealous of Beth. Beth, who had been dead seven years, who had died in a matter of months under excruciatingly painful circumstances, leaving behind the family she’d loved more than anything. How could Pauline be jealous of Beth? How could she begrudge Jenna a missive filled with motherly love and advice? Well, Pauline hadn’t been granted access to the Notebook, a fact that bugged the shit out of her, but as Doug pointed out, the Notebook was private. It was Jenna’s choice to share it or not share it. Pauline was further bothered because she had offered to take Jenna shopping for a wedding dress and Jenna had informed Pauline that she would be wearing Beth’s dress (per the Notebook). Pauline had suggested calla lilies in the bridal bouquet; Jenna was going with limelight hydrangeas and tight white peonies (per the Notebook). Pauline had wanted herself and Doug listed on the invitation by name, but Jenna had gone with this wording: Jennifer Bailey Carmichael and Stuart James Graham, along with their families, invite you to share in the celebration of their wedding (per the Notebook).

Doug had gently advised Pauline to back off where the wedding was concerned. Pauline had a daughter of her own. When it was Rhonda’s turn to get married, Pauline could interfere all she wanted.

“When Rhonda gets married?” Pauline had exclaimed.

“Yes,” Doug said.

“She’ll never get married!” Pauline said. “She’s never had a relationship last more than six weeks.”

This was true. Rhonda had pretty, dark hair like her mother, and she was very thin. Too thin, if you asked Doug. She spent something like five hours a day at the gym. Going to the gym was Rhonda’s job, and freelance graphic design was a hobby from which she received the occasional paycheck. She was thirty-eight years old, and Arthur Tonelli still paid her rent and gave her an allowance. At thirty-eight! The reason Rhonda’s relationships didn’t last was because she was impossible to please. She was negative, dour, and unpleasant. She never smiled. The reason Rhonda worked freelance was because she’d lost her last three office jobs due to “problems cooperating with coworkers” and “insufficient interpersonal skills with clients.” Which meant: no one liked her. Except, of course, for Pauline. Mother and daughter were best friends. They told each other everything; there was absolutely no filter. This fact alone made Doug uncomfortable around Rhonda. He was sure that Rhonda knew how frequently he and Pauline made love (lately about once a month), as well as the results of his prostate exam and the cost of his bridgework.

Pauline was right: Rhonda would never get married. Pauline would never become a grandmother. And so could Doug really blame her for clinging to his family with such desperation?

Pauline burst into the bedroom, and Doug sat straight up in bed. He had fallen asleep; his mouth was cottony and still tasted faintly of peanut butter.

“Hi,” he said.

“Were you sleeping?” she asked. She was wearing her tennis clothes but had removed her shoes and socks, and so Doug smelled, or imagined he could smell, her feet.

“I took a nap,” he said. “I was tired, and I thought it would be a good idea, considering the drive.” Doug studied his wife. She was an ample woman with large breasts and wide hips; she was the despondent possessor of what she called a “muffin top,” which kept her constantly dieting. Food wasn’t just food with Pauline; it was a daily challenge. She always started off well-power walking along the Silvermine River with two other women from the neighborhood and coming home to eat a bowl of yogurt with berries. But then there was a thick sandwich with fries at the country club, followed by the two pieces of pound cake she ate at book group, and not only would Doug have to hear about it when he got home from work, but he would have to share in Pauline’s punishment: a dinner that consisted of grilled green beans and eggplant or a bowl of Special K.

Beth had been such a good cook. Doug would kill to taste her creamy mac and cheese or her pan-fried pork chops smothered with mushroom sauce. But he didn’t like to compare.

He was glad to see Pauline had actually gone to play tennis. Her dark hair was in a ponytail, and her forehead had a sheen of sweat that gave her a certain glow. The short, pleated skirt showed off her legs, which were her best feature. Sometimes Pauline went to the club to “play tennis,” but the courts would be booked, so instead she would sit at the bar with Christine Potter and Alice Quincy and drink chardonnay for two hours, and Pauline would come home feeling combative.

Pauline was a prodigious drinker of chardonnay. Doug remembered that during the divorce proceedings, Arthur had referred to her as “the wino.” Doug had found that mean and unnecessary at the time, but he realized now that Arthur had not been complaining for no reason.

“How was tennis?” Doug asked.

“Fine,” Pauline said. “It felt good to work out some of my anxiety.”

Anxiety? Doug thought. He knew an attentive husband would ask about the source of his wife’s anxiety, but Doug didn’t want to ask. Then he realized that Pauline had anxiety about the upcoming weekend. He remembered the Notebook, now safely tucked into his suitcase.

He swung his feet to the floor and loosened his tie. “Pauline,” he said.

She pulled her top off over her head and unhooked her sturdy white bra. Her breasts were set free. Had they always hung so low, he wondered?

“I’m going to shower,” she said. “And then I have to finish packing. We’re having lamb chops for dinner.” She wriggled out of her skirt and underwear. She stood before him naked. Pauline was not an unlovely woman; if he touched her, he knew her skin would be soft and smooth and warm. Once upon a time, Doug had been very attracted to Pauline; their lovemaking had always been a strong point between them. He allowed himself to think about having wild, ravishing sex right now, maybe up against the closet door. He willed himself to feel a stir of arousal. He envisioned his mouth on Pauline’s neck, her hand down his pants.

Nothing.

This was not good.

“Pauline.”

She turned to face him, panicked. She sensed, maybe, that he was after sex-which she explicitly did not allow during daylight hours.

“What?” she said.

“Did you take the Notebook from the restaurant last night?”

“What notebook?”

Doug closed his eyes, wishing she hadn’t just said that. He lowered his voice, the way he would have for a hostile witness or a client who insisted on lying to him despite the fact that he had been hired to help.

“You know which notebook.”

Pauline’s forehead wrinkled and her eyes widened, and she did, at that moment, resemble Rhonda very strongly, which did not improve her case. “You mean the green notebook? Jenna’s notebook?”

“Yes,” Doug said. “Jenna’s notebook. I found it downstairs. Did you take it?” The question was ridiculous-of course she’d taken it-but Doug wanted to hear her admit to it.

“Why are you being so weird?”she asked.

“Define ‘weird,’ ” he said.

“ ‘Define weird.’ Don’t harass me, counselor. Save it for the courtroom.” Pauline took a step toward the bathroom, but Doug wasn’t going to let her escape. He stood up.

“Pauline.”

“I need to get in the shower,” she said. “I’m not going to stand around naked while you accuse me of things.”

Doug followed Pauline to the bathroom. He stood in the doorway as she turned on the water. This was the master bath she had shared with Arthur Tonelli for over twenty years. Pauline and Arthur had built this house together; they had picked out the tile and the sink and the fixtures. For the first few years of their marriage, Doug had felt like an impostor in this bathroom. What was he doing using Arthur Tonelli’s bathroom? What was he doing sleeping with Arthur Tonelli’s wife? But by now Doug had grown used to it. He and Beth had renovated their 1836 colonial on the Post Road until it was exactly to their taste, but after Beth died, it occurred to Doug that material things-even entire rooms-held no meaning. A bathroom was a bathroom was a bathroom.

“Did you take the Notebook?” Doug asked.

Pauline tested the water with her hand. She did not answer.

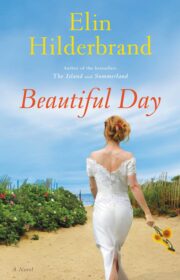

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.