Madaket was low-key by Nantucket standards. There was one restaurant that had changed hands a few times-in Margot’s memory it had been called 27 Curves, and then the Westender, which had served a popular drink called the Madaket Mystery. Now it was a popular Tex-Mex place called Millie’s, named after an iconic but scary-looking woman who had worked for the Coast Guard named Madaket Millie.

Beth had loved Madaket; she found its simplicity pleasing. There was no flash, no cachet, very little to see except for the natural beauty of the sun setting each night and the quiet splendor of Madaket Harbor, which was small and picturesque and surrounded by eelgrass.

Margot traveled the road to Madaket slowly, searching the bike path for Jenna. There were, in fact, twenty-seven curves in the road that took one past the dump, then the trails of Ram’s Pasture, then the pond where Beth used to take Margot and her siblings turtling-four sturdy sticks, a ball of string, and a pound of raw chicken equaled an afternoon of hilarity. Both Kevin and Nick had always ended up in the pond with the turtles.

Margot didn’t see Jenna on the bike path. This was impossible, right? Margot tried to calculate time. If Jenna had left the house when Margot suspected she had, and if she’d stopped at Brant Point Lighthouse, then Margot would have seen Jenna on the bike path, either coming or going. There was only one way out and one way in. There were a few stands of trees and a couple of grassy knolls, but otherwise nowhere to hide.

Margot reached the parking lot of Madaket Beach. She climbed out of the car and wandered over to the wooden bridge that looked out on both Madaket Harbor and the ocean.

Madaket Mystery, Margot thought. Where is my sister?

It occurred to Margot then that maybe she was wrong. Maybe Jenna hadn’t gone on a quest for their mother. Maybe Jenna had ridden her bike to the airport and flown back to New York.

Margot pulled out Rhonda’s phone and dialed the number of the house. Five rings, six rings… there was no answering machine. The phone would just ring forever until someone picked it up. There were a dozen people in residence; someone had to be home. But answering the phone was one of the things the rest of the family left to Margot. How long would it take someone to realize she wasn’t there?

Finally the ringing stopped. There were some muffled sounds, then a froggy “Hello?”

Margot paused. It sounded like Jenna. Had Jenna made it back? Had she possibly never left? Had she found a quiet corner of the house to hide and fallen back to sleep?

Margot said, “Jenna?”

“Um,” the voice said. “No. This is Finn.”

“Oh,” Margot said. “This is Margot.”

“Uh-huh,” Finn said. “I know.”

Margot said, “Is Jenna there? Is she at the house?”

“No,” Finn said.

“Have you heard from her since I saw you last?” Margot asked.

“I’ve sent six texts and left her three voice mails,” Finn said. “And I’ve gotten nothing back. She hates me, I think, because…”

Margot understood why Jenna might hate Finn right now. “Stop. I can’t get in the middle of this,” Margot said. “I’m just trying to find Jenna.”

“Find Jenna?” Finn said. “What does that mean?”

Margot closed her eyes and inhaled through her nose. Madaket Harbor had its own smell, ripe and marshy. Margot could go back to the house and pick up Finn, and this would become the story of the sister and the shameless, irresponsible best friend hunting down the runaway bride.

That’s my decision, Jenna had said. And I’ve made it. I am not marrying Stuart tomorrow.

“I have to go,” Margot said, and she hung up.

She had a hard time finding a parking spot near the church. It was July; the streets were lined with Hummers and Jeeps and Land Rovers like Margot’s. Margot felt a sense of indignation at all the summer visitors, even though she was one herself. She drove around and around-Centre Street, Gay Street, Quince Street, Hussey Street. She needed a spot. It was five minutes to eleven, which was the time they were due at the salon. Margot couldn’t bear to think about Roger. Would he be attending to the 168 details of this wedding that needed his attention, or was he throwing darts in his garage, or was he out surfcasting?

Surfcasting, Griff, the kissing. Margot needed a parking space. She had waved back at Griff, but lamely. What would he make of that? What would he be thinking? The one thing I miss about being married is having someone to talk to late at night, someone to tell the stupid stuff. Did Roger have a picture of Jenna’s face plastered to his dartboard? Was he trying to stick her between the eyes? He would get paid regardless; their father would lose a lot of money if Jenna canceled, but of course that was no reason to go through with the wedding. Edge was coming today, or so Doug had said, but Margot was trying not to care. Of course she did care, but that caring was buried under her concern for Jenna and her urgent desire to salvage the wedding, and her pressing need for a parking space.

In front of her, someone pulled out.

Hallelujah, praise the Lord, Margot thought. She was, after all, going to church.

The Congregational Church, otherwise known as the north church or the white spire church (as opposed to the south church, or the clock tower church, which was Unitarian) was the final place that Beth’s ashes had been scattered. Beth wasn’t a member of this church; she was Episcopalian and had attended St. Paul’s with the rest of the family. Beth had asked for her ashes to be scattered from the Congregational Church tower because it looked out over the whole island. Doug, fearing that tossing his wife’s remains from the tower window might be frowned upon by the church staff, or possibly even deemed illegal, had suggested they smuggle Beth’s ashes up the stairs. They had gone at the very end of the day, after all the other tourists had vacated, and the surreptitious nature of their mission had made it feel mischievous, even fun-and the somberness of the occasion had been alleviated a bit. Margot had stuffed the box of ashes in her Fendi hobo bag, and Kevin had pried open a window at the top. Beth’s remains had fallen softly, like snowflakes. Most of her ashes had landed on the church’s green lawn, but Margot imagined that bits had been carried farther afield by the breeze. She lay in the treetops, on the gambrel roofs; she dusted the streets and fertilized the pocket gardens.

Margot entered the church and checked the sanctuary for Jenna. It was deserted.

The Congregationalists normally asked a volunteer to man the station by the stairway that led to the tower. But today the station was unoccupied. There was a table with a small basket and a card asking for donations of any amount. Margot had no money on her. She silently apologized as she headed up the stairs.

Up, up, up. The stairway was unventilated, and Margot grew dizzy. Those martinis, all that wine, four bites of lobster, Elvis Costello, Warren Zevon, Griff’s brother killed in a highway accident. Chance’s mother at the groomsmen’s house at the same time as Ann Graham. Was that awkward? What was it like for Ann to see the woman whom her husband had had an affair with so many years ago? Margot would someday meet Lily the Pilates instructor; Margot would probably be invited to the wedding, since she and Drum Sr. were still friends. Margot used to love to watch Drum surf; she had been unable to resist him. All her children had his magic, if that was what it was, despite Carson’s near flunking and Ellie’s hoarding; they were all illuminated from within, which was a characteristic inherited from Drum, not from her. Kevin was an ass, Margot didn’t know how Beanie could stand him, and yet she’d been standing him just fine since she was fourteen years old. So there, Margot thought. Love did last. She wondered if her father had read the last page of the Notebook. She must remind him.

Margot was huffing by the time she reached the final flight of stairs. She couldn’t think about anything but the pain in her lungs. And water-she was dying of thirst.

At the top of the tower was the room with the windows. Standing at the window facing east-toward their house on Orange Street-was Jenna.

Margot gasped. She realized she hadn’t actually expected to find anyone up here, perhaps least of all the person she was looking for.

“Hey,” Jenna said. She sounded unsurprised and unimpressed. She was wearing the backless peach dress, which was now so bedraggled that she resembled a character from one of the stories they’d read as children-a street urchin from Dickens, Sara Crewe from A Little Princess, the Little Match Girl. She wore no shoes. If anyone but Margot had discovered Jenna up here, they would have called the police.

“Hey,” Margot said. She tried to keep her voice tender. She wasn’t positive that Jenna hadn’t completely lost her mind.

“I saw you walking up the street,” Jenna said. “I knew you were coming.”

“I had a hard time finding a parking spot,” Margot said. “Have you been here long?”

Jenna shrugged. “A little while.”

Margot moved closer to Jenna. Her eyes were puffy, and her face was streaked with tears, although she wasn’t crying now. She was just staring out the window, over the streets of town and the blue scoop of harbor. Margot followed her gaze. Something about this vantage point transported Margot back 150 years, to the days of Alfred Coates Hamilton and the whaling industry, when Nantucket had been responsible for most of the country’s oil production. Women had stood on rooftops, scanning the horizon for the ships that their husbands or fathers or brothers were sailing on.

“I have a question,” Margot said.

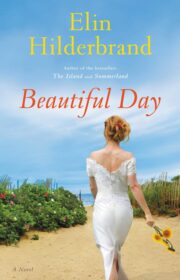

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.