“Hi, Mom,” he said.

Of her three boys, H.W. was the least complicated. As a child, Ann and Jim had nicknamed him “Pup,” short for “puppy,” because he was just about that easy to please. Whereas Stuart was the dutiful firstborn and Ryan was the emotionally complex aesthete, all H.W. needed was to be run, fed, and put to bed. The occasional pat on the head.

“Hi, honey,” Ann said. “Is your father here?”

“Dad?” H.W. said. He turned around and peered into the house. “Hey, is Dad here?”

“No,” a voice said. Ryan appeared, smelling of aftershave, his hair damp. “Hi, Mom.”

Ann stepped into the rental house. It reeked of mold and cigarettes and beer. On the coffee table, she spied a dirty ashtray and empty bottles of Stella and plastic cups with quarters lying in the bottom. There was a sad-looking tweedy green sofa and a recliner in mustard yellow vinyl and a clock on the wall meant to look like a ship’s wheel. On the walls hung some truly atrocious nautical paintings. SportsCenter was muted on the big flat-screen TV, which looked as unlikely as a spaceship in the middle of the living room.

“Dad’s not here?” she asked Ryan.

“No,” he said.

“He hasn’t been here at all? Last night? This morning?”

“No,” Ryan said. He cocked his head. “Mom?”

Ann deflected his concern. She nodded at the walls. “Nice place,” she said.

“It’s like we’ve been beamed back thirty years to a time-share decorated by Carol Brady after the divorce and meth addiction,” Ryan said. “Jethro wants to burn it down solely in the name of good taste.”

“Yeah, I’ll bet,” Ann said. On the far wall was a Thomas Kinkade print.

“But we drank and smoked like naughty schoolchildren,” Ryan said. “Went to bed so blotto that the plastic venetian blinds in the windows seemed whimsical.”

At that moment, Chance came down the stairs, wearing only boxer shorts. He was so long and lean and pale that seeing him in only underwear seemed indecent. Ann averted her eyes.

“Hey, Senator,” Chance said.

“Hi,” Ann said. “How are you feeling, sweetie?”

He shrugged. “Okay, I guess,” he said. “I can breathe.”

“Good,” Ann said. She had thought Jim would be here, he wasn’t here, that was bad, that was awful, and now she had to explain, or make up a story. Helen, she thought. Where was Helen staying? Did she dare ask Chance?

Suddenly she felt hands on her shoulders.

“Hey, beautiful lady,” Jethro said. He kissed the top of her head.

“Hey,” Ann bleated. She felt like a little lost lamb. To avoid further questioning, she gave herself a tour of the house. She stumbled through a doorway into the kitchen. A young woman was sitting at the rectangular Formica table, smoking a cigarette. She was wearing an oversized N.C. State T-shirt, and not much else. It was H.W. ’s T-shirt. And then Ann got it.

“Oh,” she said. “Hello. I’m Ann Graham.”

The woman stood immediately, setting her cigarette in a half clamshell that served as an ashtray, and held out her hand. “Autumn Donahue,” she said. She had hair the color of shiny pennies, and lovely long legs. “I’m one of the bridesmaids. I was Jenna’s roommate at William and Mary.”

Ann reverted to state senator mode and shook the woman’s hand. “Nice to meet you, Autumn.”

Ryan entered the kitchen. “I don’t understand why you’re looking for Dad at eight thirty in the morning.”

“He got up early and went out,” Ann said. “I thought he might have come here.”

“You’re a terrible liar,” Ryan said. He eyed Jethro. “Isn’t she a terrible liar?”

“Terrible,” Jethro said.

“Plus, I wanted to make you all breakfast,” Ann said. She opened the refrigerator, hoping her bluff hadn’t just been called, and exhaled when she saw eggs and milk and butter and a hunk of aged cheddar (Ryan and Jethro must have done the shopping) and a container of blueberries and a half gallon of orange juice.

“I’m hungry!” Autumn said.

Ann took out a mixing bowl and cracked all the eggs; she added milk, salt and pepper, a handful of grated cheddar. She melted butter in a frying pan. She thought, Where the hell is Jim? It’s the morning of Stuart’s wedding, for God’s sake. Ann felt her temper smoking and sizzling like the hot pan. And yet how could she be angry when she had asked him to leave? She had told him to get out.

A Quaalude would be nice right now, she thought.

She poured the egg mixture into the pan, popped a couple of pieces of seeded whole-grain bread into the rusty toaster, and got to work on the coffee. Starbucks, in the freezer. Thank God for small blessings.

Ryan said, “Mom, you do not have to do this. I’m sure you’d rather be having breakfast at your hotel.”

“I’m fine!” Ann sang out. “It’s the last morning I’ll ever be able to do this for Stuart. Tomorrow, he’ll belong to Jenna.”

“Whoa!” Ryan said. “Sappy alert.”

“Where is Stuart, anyway?” Ann asked.

Ryan said, “The door to his room is closed. I knocked earlier, fearing he had been asphyxiated by the synthetic bed linens, and he told me to go away.” Ryan lowered his voice. “I guess he and Jenna had a spat last night concerning She Who Shall Not Be Named.”

“A spat?” Ann said. A spat the night before the wedding wasn’t good. A spat about She Who Shall Not Be Named wasn’t good at all. Why must love be so agonizing? Ann wondered. She moved the eggs around the pan, slowly, over low heat, so they would be nice and creamy. “This reminds me of when we used to visit Stuart at the Sig Ep house. Remember when we used to do that?”

“The Sig Ep house was nicer,” Ryan said.

“The Sig Ep house was nicer,” Ann agreed, and they both laughed.

A few minutes later, Ann had managed to plate, on mismatched Fiesta ware, scrambled eggs, toast, juice, coffee, and blueberries with a little sugar. They crowded around the sad Formica table: H.W., Ryan, Jethro, Chance, and Autumn.

“We need Stuart,” Ann said. “This is supposed to be for him.”

“I just knocked on his door,” Chance said. “He told me he’d be down in a minute.”

“It’ll all be gone in a minute,” H.W. said, helping himself to a second piece of toast. “No grits?”

“Grits?” Ryan said. “Please don’t tell me you still eat grits.”

“Every day,” H.W. said.

“Oh, my God,” Ryan said. “My twin brother is Jeff Foxworthy.”

“Well, your boyfriend is André Leon Talley,” H.W. said. He grinned at Jethro. “No disrespect, man.”

“None taken,” Jethro said. “Love ALT.”

Autumn pointed her fork at H.W. “I’m impressed you know who André Leon Talley is.”

“What?” H.W. said. “I have been known to read the occasional issue of Vogue.”

“Oh, come on,” Ryan said.

“Hot women half dressed,” H.W. said. He hooted and gave Chance a high five.

Ryan said, “Mom, aren’t you eating?”

“Oh, no,” Ann said. “I couldn’t possibly.”

She left the kitchen to retrieve her purse from the scratchy green sofa and to check her phone. No new messages, 3 percent battery. She stepped outside to use the last bit of juice to call Jim’s cell phone. She should have called him from the taxi, but she had been sure he would be here, with the kids.

The phone rang and rang and rang. She got Jim’s voice mail, but before Ann could leave a message, her battery died.

Where are you? Ann thought. Where the hell did you go?

Ann and Jim had joined the wine-tasting group in 1992. The invitation had come from a woman named Shell Phillips, who had recently moved to Durham from Philadelphia when her husband took a job in the physics department at Duke. Shell Phillips was a northerner, which-although the Civil War was 125 years in the past-still marked her as a potential enemy. She was from the Main Line, she said, Haverford, she said, and Ann bobbed her head, pretending to know what this meant. Shell Phillips had introduced herself to Ann at the Kroger. Hello, Senator Graham, I’ve been so wanting to meet you, someone pointed you out to me the other night at the Washington Duke.

Shell Phillips had shiny, dark hair that she wore in a bob tucked behind her ears, and a strand of pearls and pearl earrings. Clearly she was trying to fit in; Ann had heard that most northern women went to the grocery store in their yoga clothes.

Shell Phillips asked if Ann and Jim might want to join a wine-tasting group that Shell was putting together. Just a fun thing, they’d done it in Haverford, five or six couples, once a month. A different couple would be responsible for hosting each month, choosing a varietal and getting a case of different labels so that they could compare and contrast. Hors d’oeuvres to complement the wine.

Just a little social thing, Shell Phillips said. Like a cocktail party, really. We had such fun with it back home. It would be wonderful if you and your husband would join us.

Of course, Ann said. We’d love to be part of it.

She had committed without asking Jim because despite her natural skepticism toward northerners, she thought a wine-tasting group might add some flair to their social life. She and Jim could stand to learn a little about wine; when Ann was at the Washington Duke or somewhere else for dinner, she normally defaulted and ordered a glass of white Zinfandel or the house Chablis. Shell Phillips might have assumed all southerners made their own wine. Any which way, Ann felt flattered that someone had sought her out for a reason that had nothing to do with local politics.

Yes, yes, yes, count them in.

There had been six couples. In addition to Ann and Jim, and Shell and her husband, Clayton Phillips, there were the Lewises, Olivia and Robert, whom Ann and Jim were already friends with, as well as three couples unfamiliar to them: the Greenes, the Fairlees, and Nathaniel and Helen Oppenheimer.

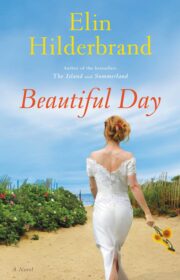

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.