Jim and the yacht club manager kept imploring people to back up so that Chance could have some air. Helen was kneeling by Chance’s head, smoothing his hair, patting his mottled cheeks. She seemed elegant and glamorous, even on her knees. She looked up at Ann. “What did he eat?” she demanded.

The question was nearly accusatory, as though Ann were somehow to blame. She felt like the wicked stepmother who had given him a poison apple.

“He ate a mussel,” Ann said.

Helen returned her attention to Chance, and Ann felt a creeping sense of shame. Chance had said he’d never eaten a mussel before, and Ann had said, They’re yummy, you’ll love them. She hadn’t told him to eat it; he had tried it of his own volition. But she also hadn’t given him a warning about allergies. She hadn’t even considered allergies. Hadn’t Chance been allergic to milk as a child? Ann thought she recalled hearing that, but she wasn’t positive. He wasn’t her child. But lots of people were allergic to shellfish. Should she have warned him instead of encouraging him?

The paramedics stormed in, all black uniforms and squawking police scanners. The lead paramedic was a woman in her twenties with wide hips and a brown ponytail. “What’d he eat?”

“A mussel,” Helen said.

There was talk and fussing, another shot of something, an oxygen mask. They lifted Chance onto a gurney.

Helen said, “May I ride in the ambulance?”

“You’re his mother?” the paramedic asked.

“And I’m his father,” Jim said. Jim and Helen were now standing side by side, unified in their roles as Chance’s parents.

“No family in the ambulance. You can follow us to the hospital.”

“Oh, please,” Helen said. “He’s only a teenager. Please let me come in the ambulance.”

“Sorry, ma’am,” the paramedic said. They whisked Chance down the hall and out the front doors.

Helen gazed at Jim-in her heels, she was nearly as tall as he was-and burst into tears. Ann watched Jim fight what must have been a dozen conflicting emotions. Did he want to comfort her? Ann wondered.

He patted her shoulder. “He’ll be fine,” Jim said.

“We have to go to the hospital,” Helen said. “Can I get a ride with y’all?”

“Okay,” Jim said. He took Ann by the shoulder. “Let’s go.”

Ann hesitated. An old, dark emotion bubbled up in her, as thick and viscous as tar. She didn’t want to go anywhere with Jim and Helen. She would be an outsider; she wasn’t Chance’s mother. She loved Chance and was sick with worry, but she didn’t belong at the hospital with Jim and Helen. However, she didn’t want Jim and Helen to go without her, either. She couldn’t decide what to do. It was an impossible situation.

Suddenly Stuart and Ryan and H.W. were upon her. “Mom?” Ryan said. He circled his arm around her shoulders.

Stuart said, “Is he going to be okay?”

Jim said, “Your mother and I are going to the hospital with Helen.”

“Actually, I’m going to stay here,” Ann said. To Jim she said, “You go. Please keep me posted.”

“What?” Jim said.

Helen shifted from foot to foot. “Can we please leave?”

“Go,” Ann said. She gave Jim’s arm a push.

“Would you stop acting like a child?” he whispered.

“I need to stay here,” Ann said. “It’s the rehearsal dinner. It’s Stuart’s wedding.” These words sounded reasonable to her ears, but was she acting like a child? She didn’t want to be a third wheel with Jim and Helen. She didn’t want to have to watch them together in their roles as Mom and Dad. She hated them both at that moment; she hated what they’d done to her. She couldn’t believe that she had somehow thought having Helen at the wedding would be a healing experience. It was turning out to be the opposite of healing.

“Ann,” Jim said. “Please come. I need you.”

Ann smiled her senatorial smile. “I’m going to represent here. You go, and let me know how he’s doing.” She took Ryan’s arm and headed back into the party.

Ryan put his hand on her lower back and whispered in her ear, “Well done, Mother. As always.”

Ann fixed herself a plate of food and went to sit with the Lewises, the Cohens, and the Shelbys. On the way, she stopped at each table-most of them filled with people she didn’t know-and reassured everyone that Chance would be fine, he was on his way to the hospital to get checked out. As a politician, Ann had spent her career managing crises; the soothing smiles and words and gestures came naturally to her. She wouldn’t let herself think about Helen and Jim side by side in the front seat of the rental car, or about how Helen’s intoxicating perfume would linger there for Ann and Jim to smell every time they opened the door and climbed in.

Violet, you’re turning violet. All the nights that Ann had read Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to her boys, Jim had been living in Brightleaf Square making love to the woman he was now driving to the hospital.

Ann closed her eyes against the vision, but all she saw was yellow.

Ann sat next to Olivia, who squeezed the heck out of Ann’s forearm but said nothing except “I’m sure he’ll be fine.”

“Of course he’ll be fine,” Ann said. She beamed vacantly at her friends, all of whom were wearing plastic bibs and attacking their lobsters. The conversation turned to allergic reactions that people had witnessed or merely heard of secondhand-a man going comatose over his bowl of New England clam chowder, a fifteen-year-old girl dying because she kissed her boyfriend, who had eaten peanut butter for lunch. Meanwhile, in the background, the orchestra played “Mack the Knife” and “Fly Me to the Moon.” Couples danced. Stuart and Jenna got up to dance, and there was a smattering of applause. Those two made such a sweet, earnest, clean-cut, wholesome, good-looking couple. Thank God Stuart had broken up with She Who Shall Not Be Named. When Ann used to gaze upon Stuart and Crissy Pine, she had had visions of expensive vacations and overindulged children; she imagined Stuart trapped in a soulless McMansion with a perpetually unhappy wife. Stuart and Jenna’s union would be meaningful and strong; they would live with a social conscience, serve on nonprofit boards, and be role models, envied by their friends and neighbors.

Ann picked at a boiled red-skinned potato. Yes, it all looked good from here, but who knew what would happen.

The Cohens got up to dance, and Ann buttered a roll that she had no intention of eating. She checked her cell phone: nothing. Jim and Helen would be at the hospital by now. They would be sitting in the waiting room together, awaiting news. People who saw them would think they were a couple.

Tap on the shoulder. Jethro.

“Dance with me,” he said.

“I don’t feel up to it,” Ann said.

“You have to,” Jethro said. “You need to show these northerners you didn’t bring me along as chattel.”

Ann made a face. “Please spare me the self-deprecating black humor.” But Ann then admitted she was powerless to resist Jethro under any circumstances. “Only you,” she said.

She accepted his hand and followed him to the dance floor, where he swung her expertly around. Ann and Jim had taken dance lessons right after getting married the second time; it was one of the things they’d made an effort to do together, along with couples Bible study, and antiquing in Asheville, and trout fishing on the Eno River in a flat-bottomed rowboat Jim had bought. They had been happy the second time. Happy until thirty minutes ago. Now Ann could feel herself cracking inside, a ravine opening up.

The song ended. She and Jethro clapped. She kissed his cheek. Ryan had told Ann and Jim that he was gay during Thanksgiving break of his freshman year in college. Ann would say she had handled it well. It wasn’t exactly her wish for him, only because she feared his life would be difficult-and of course there was the issue of grandchildren. Jim had taken the news in stride. He had said, “I’m in no position to judge you, son. But for crying out loud, be careful.” Ann hadn’t been able to predict then how she would adore her son’s future boyfriend. She felt even closer to Jethro than she did to Jenna.

She looked at him frankly. “I shouldn’t have invited Helen to this fucking wedding.”

He grinned, and Ann spied his two overlapping front teeth, and she imagined him as an adolescent in Cabrini-Green, saving his money to buy copies of Esquire and GQ. “I love you, Annie,” he said.

She hugged him. “I love you, too,” she said. “Never leave us.”

That was a wonderful moment, perhaps Ann’s favorite moment of the wedding weekend so far. She wondered what everyone else made of their clan-Ryan with his black boyfriend, Jim with the wife, the mistress-ex-wife, and the love child. Ann stopped at the Carmichael table, where Doug was sitting with Pauline and Pauline’s daughter, who was a carbon copy of Pauline, but thirty years younger. The three of them looked perfectly miserable.

Ann remembered Pauline’s words and her hot cashew breath. Do you ever feel like maybe your marriage isn’t exactly what you thought it was?

“Great party!” Ann said.

Doug looked at his watch. The band launched into a Neil Diamond song, and some of the younger people got up to dance.

Jethro escorted Ann back to her table, where she checked her phone. Nothing.

Olivia said, “Eat something, please, Ann.”

“I can’t,” Ann said.

Olivia gave her a knowing look, a look Ann might last have seen twenty years earlier when Jim first left and Ann dropped to ninety-seven pounds.

“I’m going for a little walk,” Ann said.

“Want company?” Olivia asked.

Ann shook her head. She put on her wrap and headed out the back doors across the patio and down the brick walk that cut between swaths of green lawn.

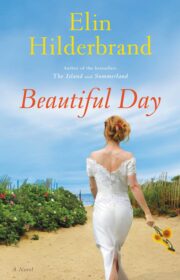

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.