Margot did not see Edge.

She surveyed the room again, checking every single face. Edge was only about five foot ten, with a head of close-cropped silver-gray hair. He had that Roman nose, lovely hazel eyes, and an elegance-hand-tailored suits, polished Gucci loafers, a Girard-Perregaux watch. His deportment oozed importance and self-confidence. It was incredibly sexy. If he were in the room, Margot would have homed in on him in a matter of seconds.

She checked the time: it was five of seven.

He wasn’t here.

Maybe the texts he’d sent last night were texts saying he wasn’t coming. Edge was a habitual canceler. More than half the time they had plans, something came up: Audrey had the flu, or one of his sons had gotten his car impounded, or a client had been threatened by her soon-to-be-ex-husband, or his most famous client-a legendary rock star-had ended up back in rehab and needed Edge to deal with the custody arrangement for his children. But it had never occurred to Margot that Edge might cancel on Jenna’s wedding.

There was only one person she could ask.

But no, she couldn’t. It would send up a red flag.

But she had to.

Margot threaded her way through the crowd and reached her father just as he was excusing himself from Everett and Kay Bailey. Margot would have liked to talk to Ev and Kay-all her mother’s cousins were fun, good-natured people-but Margot didn’t want to do it right now. She would talk to them tomorrow at the wedding. She waited until Doug and the Baileys parted, then she snatched her father’s arm.

“Oh, good,” he said. “You’re here. Where are Nick and Finn?”

“At the house,” Margot said. “Getting ready.”

“I thought you were going to wait for them and drive them down.”

“They wanted to walk,” Margot lied.

“Well, they’d better hurry up, or they’re going to miss dinner,” Doug said. “They’re serving in five minutes.”

“Right,” Margot said. She took a breath. Launch? Or abort mission?

She had to know.

“So,” she said. “Representation from Garrett, Parker, and Spence seems a little light. Isn’t Edge coming?”

“He thought he’d be here tonight,” Doug said. “But I got a call from him about an hour ago. Today in court was a disaster, I guess, and he and Rosalie were still finishing the paperwork, and he didn’t want to fight Friday night traffic on I-95. Can’t blame him for that.”

He and Rosalie finishing paperwork, Margot thought. Or he and Rosalie screwing on top of his partners desk. Or he and Rosalie taking advantage of an empty city to snare seats at the bar at Café Boulud.

“So he’s coming tomorrow?” Margot asked. She sounded panicked, even to her own ears.

Doug gave her a quizzical look. “That’s what he told me, honey,” he said.

THE NOTEBOOK, PAGE 2

The Invitations

Mail them six weeks in advance. (You don’t need your mother to tell you that, although it appears I just did.) Classic white or ivory-maybe with one subtle, tasteful detail, such as a starfish, sand dollar, or sailboat at the top. Maybe a small Nantucket? Pick a traditional font-I used to know the names of some of them, but they escape me now. Matching response card, envelope stamped.

I get the feeling you may have issues with this vision. I see you sending out something on recycled paper. I hear you claiming that Crane’s kills trees. I imagine you deciding to send your invitations via e-mail. Please, darling, do not do this!

My preferred wording is: Jennifer Bailey Carmichael and Intelligent, Sensitive Groom-to-Be, along with their families, invite you to share in the celebration of their wedding.

In my day, it was customary to list the bride’s parents by name, but my parents, as you know, were divorced, and Mother had remarried awful Major O’Hara and Daddy was living with Barbara Benson, and the whole thing was a mess, so I used the above wording, which diffused the whole issue.

No e-mail, please.

ANN

She was standing behind Chance in the buffet line when it happened. She had positioned herself there on purpose, like a sniper, waiting for Helen. Contrary to her earlier expectations, Ann wanted another shot at conversation; she wanted that thank-you, goddamn it.

Ann tapped Chance on the shoulder. “Hey, sweetie.”

Chance said, “Hey, Senator.”

Ann smiled. He always called her “Senator,” which was a good, neutral moniker-better than “Mrs. Graham” or “Ann.” Ann’s relationship with Chance had always been a tender question mark. What was their relationship, exactly? Technically, she was his stepmother, and she was the mother of his three half brothers. He was her husband’s son from another union. She had grown to know and love him, but there was a certain barrier.

The buffet included clam chowder, mussels, grilled linguiça, corn on the cob, and a pile of steaming scarlet lobsters served whole. Ann had doubts about her lobster-cracking ability; she worried about lobster guts messing the front of her dress. There were plastic bibs on the tables, but the last thing Ann wanted was to be seen wearing one.

Ahead of her, Chance loaded his plate with mussels. He turned to Ann. “I’ve never had mussels before.”

“They’re yummy, you’ll love them,” she said, which was a glib thing to say, as, living three hours from the coast, she ate mussels about once every decade.

Chance pulled one from its shell and popped it into his mouth. He nodded his head. “Interesting texture,” he said.

Ann searched the party for the yellow of Helen’s dress. She spied Helen out on the patio, talking to Stuart.

Ann had been forced to swallow a whole bunch of unpleasant facts in the past twenty years, but the worst thing was that, for a time, Helen had been a stepmother to her children. Helen had coparented them every third weekend with Jim. Ann used to question the boys when they got home from weekends with their father and Helen. What had they done? What had they eaten? Had they gone out or stayed in? Did Helen cook? Did Helen read to them at night? Did Helen let them stay up late to watch R-rated movies? Did Helen kiss them good-bye before they piled into Jim’s car at seven o’clock on Sunday evening?

What Ann had gleaned was that, in those years, Jim took on most of the duties pertaining to the three older boys, while Helen cared for Chance. Chance had been a colicky baby, Helen carried him everywhere in a sling, Chance didn’t sleep in a crib, he slept in the bed with Helen and Jim. Chance had walked early, and Helen was forever chasing him around. Helen had made chicken with biscuits once, but the biscuits were burned. (In Roanoke, Ann knew, Helen had grown up with a black housekeeper who had done all the cooking.) Jim often took the boys to McDonald’s for lunch, which was a treat for them, since Ann was sponsoring an initiative for healthier eating habits for Carolina schoolchildren and hence did not allow the kids fast food. Helen bought the boys Entenmann’s coffee cake for breakfast and let them eat it straight from the box in front of the TV on Saturday mornings. Helen sometimes yelled at the boys-or even at Jim-to help out more. Jim took the boys to the Flying Burrito for Mexican food on Sunday nights before bringing them back to Ann, and Helen and Chance always stayed home.

Ann tucked every piece of information away. To her credit, she had never demonized Helen to the boys. But she had lived in mortal fear that the boys would one day arrive home, announcing that they liked Helen better.

Just the way that Jim had once announced he liked Helen better.

It took a moment for Ann to realize that Chance was in distress. He dropped his plate on the floor, where it broke in half, and the mussel shells scattered everywhere. Ann jumped out of the way. Then she saw Chance clutching at his throat; he was puffing up, turning the color of raw meat.

“Help!” Ann shouted. She spun around, hoping to find Jim, but behind her was a stout, bald man with square glasses and a bullfrog neck. “Help him!”

A commotion ensued. Chance sank to his knees. The man behind Ann rushed to his side.

“We need an EpiPen!” he shouted. “He’s having an allergic reaction!”

Ann snatched her phone out of her purse and dialed 911. She said, “Nantucket Yacht Club, nineteen-year-old male, severe allergic reaction. Please send an ambulance! His throat is closing!”

Chance was clawing at his neck, gasping for air in a way that made it look like he was drowning right in front of them. He sought out Ann’s face; his eyes were bulging. Ann was hot with panic. She was shaking, she thought, My God, what if he dies? But then her mothering instincts kicked in. She knelt beside him.

“I’ve called an ambulance, Chance,” she said. “Help is coming.”

One of the club’s managers shot through the kitchen’s double doors holding a first aid kit, from which he pulled an EpiPen. He stabbed Chance in the thigh.

Suddenly Jim was there. “Jesus Christ!” he said. “What the hell?”

“He ate a mussel,” Ann said. “He must be allergic. He swelled right up.” It had reminded Ann of the scene from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory where Violet turns into a blueberry and the Oompa-Loompas roll her away.

And then Ann saw a flash of yellow.

“Chancey!” Helen screamed.

The epinephrine seemed to help. Chance’s color didn’t improve, but neither did it deepen, and he was still forcing wheezing breaths in and out. A crowd gathered, and urgent queries of What happened? and Who is it? circulated. Ann heard someone say, “It’s Stuart’s stepbrother,” then someone else say, “It’s the other woman’s son.” Ann turned around and to no one in particular said, “His name is Chance Graham, and he’s the groom’s half brother.”

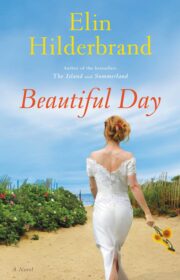

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.