“What I’m saying is that you and Stuart are tra-la-la now, everything is sunshine and lollipops, but it might still fail down the road.”

“Shut up,” Jenna said again. “Just shut the eff up. You’re not going to talk me out of it. I love Stuart.”

“Love dies,” Margot said, and she snatched up the bill.

Now Margot tried to center Jenna’s and Finn’s shining faces in the viewfinder. She snapped a picture, all hair and toothy smiles.

“Take another one, just in case,” Jenna said.

Margot took another as the boat pitched side… to… side. She grabbed one of the plastic molded chairs that were bolted to the deck. Oh, God. She breathed in through her nose, out through her mouth. It was good to be gazing at the horizon. Her three children were down in the hold of the ship, sitting in the car, playing Angry Birds and Fruit Ninja on their iDevices. The movement of the boat didn’t faze them; all three had their father’s ironclad constitution. Nothing made them sick; physically, they were warriors. But Drum Jr. was afraid of the dark, and Carson, Margot’s ten-year-old, had nearly failed the fourth grade. At the end of the year, his teacher, Ms. Wolff, had told Margot-as if she didn’t know already-that Carson wasn’t stupid, he was just lazy.

Like his father. Drum Sr. was living in San Diego, surfing and managing a fish taco stand. He hoped to buy the stand and possibly turn it into a franchise; someday he would be a baron of fish taco stands up and down the coast of California. The business plan sounded hazy to Margot, but she encouraged him nonetheless. When she met him, Drum Sr. had had a trust fund, which he’d frittered away on exotic surfing and skiing trips. His parents had bought Drum and Margot a palatial apartment on East Seventy-third Street, but his father offered nothing more in the way of cash, hoping that Drum would be inspired to get a job. But instead Drum had stayed home to care for the kids while Margot worked. Now she sent him a support check for $4,000 every month-the trade-off, along with a lump sum of $360,000, for keeping the apartment.

However, after the phone call she had received last night, she supposed the palimony payments would end. Drum Sr. had called to tell her he was getting married.

“Married?” Margot had said. “To whom?”

“Lily,” he said. “The Pilates instructor.”

Margot had never heard of Lily the Pilates instructor before, and she had never heard the kids-who flew to California the last weekend of every month, trips that were also financed by Margot-mention anyone named Lily the Pilates instructor. There had been a Caroline, a Nicole, a Sara, pronounced “Sah-RAH.” Drum had women moving through a revolving door. From what Margot could tell, girlfriends lasted three to four months, which aligned with what she knew to be his attention span.

“Well, congratulations,” Margot said. “That’s wonderful.” She sounded genuine to her own ears; she was genuine. Drum was a good guy, just not the guy for her. She had been the one to end the marriage. Drum’s laid-back approach to the world-which Margot had found so charming when she met him surfing on Nantucket-had come to drive her insane. He was unambitious at best, a slacker at worst. That being said, Margot was astonished to find she felt a twinge of-what? jealousy? anger? resentment?-at his announcement. It seemed unfair that news of Drum’s nuptials should arrive less than forty-eight hours before Jenna’s wedding.

Everyone is getting married, she thought. Everyone but me.

Jenna and Finn were as young and blond and pretty as a couple of milkmaids on a farm in Sweden. Finn looked more like Jenna than Margot did. Margot had straight black hair, the hair of a silk weaver in Beijing-and she had six inches on her sister, the height of a tribeswoman on the banks of the Amazon. She had blue eyes like Jenna, but Jenna’s were the same color as the sapphires in her engagement ring, whereas Margot’s were ice blue, the eyes of a sled dog in northern Russia.

Jenna looked exactly like their mother. And so, bizarrely, did Finn, who had grown up three houses away.

“We need to get a picture of the three of us now,” Jenna said. She took the camera from Margot and handed it to a man reading the newspaper in one of the plastic molded chairs.

“Do you mind?” Jenna asked sweetly.

The man rose. He was tall, about Margot’s age, maybe a little older; he had a day or two of scruff on his face, and he was wearing a white visor and sunglasses. He looked like he was going to Nantucket to sail in a regatta. Margot checked his left hand-no ring. No girlfriend in the vicinity, no children in his custody, just a folded copy of the Wall Street Journal now resting on his seat as he rose to take the picture. “Sure,” he said. “I’d love to.”

Margot assumed that Jenna had picked the guy on purpose; Jenna was on a mission to find Margot a boyfriend. She had no idea that Margot had allowed herself to fall in love-idiotically-with Edge Desvesnes, their father’s law partner. Edge was thrice married, thrice divorced, nineteen years Margot’s senior, and wildly inappropriate in half a dozen other ways. If Jenna had known about Margot and Edge, she would only be more eager to introduce Margot to someone else.

Margot found herself assigned to the middle, pegged between the two blond bookends.

“I can’t see your face,” Regatta Man said, nodding at Margot. “Your hat is casting a shadow.”

“Sorry,” Margot said. “I have to leave it on.”

“Oh, come on,” Jenna said. “Just for one second while he takes the picture?”

“No,” Margot said. If her skin saw the sun for even one second, she would detonate into a hundred thousand freckles. Jenna and Finn could be cavalier with their skin, they were young, but Margot would stand vigilant guard, despite the fact that she must now seem rigid and difficult to Regatta Man. She said in her most conciliatory voice, “Sorry.”

“No worries,” Regatta Man said. “Smile!” He took the picture.

There was something familiar about the guy, Margot thought. She knew him. Or maybe it was the Dramamine messing with her brain.

“Should I take one more, Margot?” he said. “Just to be safe?”

Regatta Man removed his sunglasses, and Margot felt as though she’d been slapped. She lost her footing on the deck and tipped a little. She looked into Regatta Man’s eyes to be sure. Sure enough, heterochromia iridum-dark blue perimeters with green centers. Or, as Margot had thought when she first saw him, he was a man with kaleidoscope eyes.

Before her stood Griffin Wheatley, Homecoming King. Otherwise just known as Griff. Who was, out of all the people in the world, among the top five Margot didn’t want to bump into without warning. Didn’t want to bump into at all. Maybe the top three.

“Griff!” she exclaimed. “How are you?”

“I’m good, I’m good,” he said. He cleared his throat and nervously shoved the camera back at Margot; the question of the second photo seemed to have drifted off on the breeze. Margot figured Griff was about half as uncomfortable as she was. He would be thinking of her only as the bearer of disappointing news. She was thinking of him as the worst judgment call she had made in years. Oh, God.

He said, “Did you hear I ended up taking the marketing job at Blankstar?”

Margot couldn’t decide if she should pretend to be surprised by this, or if she should admit that she had been Googling his name every single day until she was able to reassure herself that he’d landed safely. The job at Blankstar was a good one.

She changed the subject. “So why are you headed to Nantucket?” She tried to recall: Had Griff mentioned Nantucket in any of his interviews? No, she would have remembered if he had. He was from Maryland somewhere, which meant he had probably grown up going to Rehoboth or Dewey.

“I’m meeting buddies for golf,” he said.

Ah, yes, golf-of course golf, not sailing. Griff had spent two years on the lower rungs of the PGA Tour. He’d made just enough money, he said, to buy a case of beer each week and have enough left over for the Laundromat. He had lived out of the back of his Jeep Wrangler and, when he played well, at the Motel 6.

These details all came back unbidden. Margot couldn’t stand here another second. She turned to Jenna, sending a telepathic message: Get me out of here! But Jenna was checking her phone. She was texting her beloved Stuart, perhaps, or any other of the 150 guests who would gather on Saturday to drink in the sight of Jenna wearing their mother’s wedding gown.

“I’m here for my sister’s wedding,” Margot said. She chewed her bottom lip. “I’m the maid of honor.”

He lit up with amused delight, as though Margot had just told him she had been selected to rumba with Antonio Banderas on Dancing with the Stars. “That’s great!” he said.

He sounded far more enthusiastic than she felt.

She said, “Yes, Jenna is getting married on Saturday.” Margot indicated Jenna with a Vanna White flourish of her hands, but Jenna’s attention was glued to her phone. Margot was afraid to engage Jenna anyway, because what if Jenna asked how Margot and Griff knew each other?

Thankfully, Finn stepped forward. “I’m Finn Sullivan-Walker,” she said. “I’m just a lowly bridesmaid.”

Griff shook hands with Finn and laughed. “Not lowly, I’m sure.”

“Not lowly at all,” Margot said. This was the third time that Finn had made reference to the fact that she wasn’t Jenna’s maid of honor. She had been miffed when Jenna first announced her decision to Margot and Finn, over dinner at Dos Caminos. Finn had ordered three margaritas in rapid succession, then gone silent. And then she had gotten her nose out of joint about it again at the bridal shower. Finn was upset that she had been stuck writing down the list of gifts while Margot the maid of honor fashioned the bows from the gifts into a goofy hat made from a paper plate. (Jenna was supposed to wear that hat tonight, to her bachelorette party. Margot had rescued it from the overly interested paws of Ellie, her six-year-old daughter, and had transported it here, more or less intact, in a white cardboard box from E.A.T. bakery.)

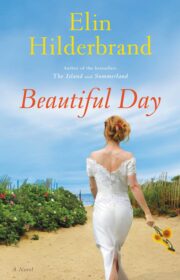

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.