Margot handed Chance the Coke. She said, “It’s nearly four thirty.” Four thirty! Margot wondered if Edge was on island yet. She got a Mexican jumping beans feeling in her belly. “I’ve got to get cracking!”

THE NOTEBOOK, PAGE 3

The Dress

You should feel no compunction or sense of duty to wear my dress; however, it is available to you. I fear you might find it too “traditional”-as I watch you now, you are twenty-one years old and you primarily wear clothes you sew yourself or that you get at Goodwill. I’m guessing it’s a phase. It was for me, too. I wore the same prairie skirt for five weeks in the spring of 1970.

The dress will fit you, or nearly. You seem to be losing weight. I’d like to believe that’s because you’re away from the dining hall food of college, but I fear it’s because of me.

My mother and I bought the dress at Priscilla of Boston, which was where every bride on the East Coast wanted to buy her dress back in those days, much like Vera Wang now. My mother and I argued because I wanted a dress with a straight skirt, whereas my mother thought I should choose something fuller. You don’t want everyone staring at your behind, she said. But guess what? I did!

The dress has been professionally cleaned and is hanging up in the far left of my cedar closet. If you need to get it altered, go to Monica at Pinpoint Bridal on West 84th Street.

I have to stop writing. I am growing too sad thinking about how captivating you will look in that dress, and how seeing you wear it might undo your father.

I am crying now, but they are tears of love.

DOUG

He wanted to say that golf had calmed him. He had played with a couple about his age named Charles and Margaret and their friend Richard, who was a decade younger and had a very, very fine drive. Doug had a wonderful time chatting with them about the elite courses they had all mutually played-Sand Hills in Nebraska, Jay Peak in Vermont, and Old Head in Ireland. They spent four delightful hours of talking about nothing but golf, and Doug couldn’t ask for a more appealing course than Sankaty Head on July nineteenth. The sun illuminated the rolling greens, the Atlantic Ocean and Sesachacha Pond, the red-and-white peppermint stick of Sankaty Lighthouse. Doug had joined his companions for lunch at the turn; he drank a cold beer and ate chilled cucumber soup and a lobster salad sandwich as they talked about the formidable prairie wind at Sand Hills. After lunch, Doug went out and slew the back nine.

He’d enjoyed another celebratory beer after the eighteenth, and then, not wanting to bother Pauline (which really meant not wanting to hear Pauline bitch about the GPS-she could never get the damn thing to work, she took it personally, as if the woman whose voice gave directions was an enemy of hers), he took a cab back to the house. Even the cab ride had been relaxing. Doug put the windows down and gazed out at the pretty cottages with their lovely gardens, their gray shingles and neat white trim, their sturdy widow’s walks. He felt better than he had in months. Spending the day by himself playing golf was just what he needed.

He had believed, during the fifteen minutes in the cab, that everything would correct itself. He didn’t need to make any drastic changes. He had been frazzled the day before with his own version of prewedding jitters. Nothing more.

But the second he entered the master bedroom-a bedroom he remembered his grandparents sleeping in, then his parents, then him and Beth-and saw Pauline sitting at this grandmother’s dressing table, fixing her hair, he thought, Oh, no, no, no. This is all wrong.

She must have noticed his expression because she said, “You hate the suit.”

“The suit?” he said.

She stood up and yanked at the hem of her jacket. “I didn’t want anything too flashy. They’re so conservative at the yacht club. All the old biddies with their pearls and their Pappagallo flats.”

Doug looked at his wife in her blue suit. It was a tad matronly, true, reminiscent of Barbara Bush or Margaret Thatcher, and Doug could never in a million years imagine Beth wearing such a suit-but the suit wasn’t the problem. It was the woman inside the suit.

“The suit looks fine,” he said.

“Then why the long face?” Pauline asked. “Did you hook your drives?”

Doug sat on the bed and removed his shoes. He had a house full of people downstairs and more people coming to the yacht club. He had to get in the right frame of mind to play host. He had to follow the advice he had glibly given so many of his clients: fake it to make it.

“My drives were fine,” he said. Pauline said things like “Did you hook your drives” to make it sound like she understood golf and cared about his game, but she didn’t. He had never hooked a drive in all his life; he was a slicer. “I played pretty well, actually.”

“What did you shoot?”

“A seventy-nine,” he said. He wasn’t sure why he fudged the number for Pauline’s sake; he could have said he’d shot a 103, and she still would have said:

“That’s wonderful, honey.”

She sat next to him on the bed and started kneading the muscles in his shoulder. She must have realized something was very wrong, because unsolicited touches from Pauline were few and far between. But he wasn’t in the mood to be touched by Pauline. He might never be in the mood again.

He stood up. “I have to get ready,” he said.

It was only the rehearsal, but as they stood in the vestibule of the church, it felt like a big moment. Everyone else had processed before them-first Autumn on the arm of one of the twins, then Rhonda and the tall, nearly albino half brother, then Kevin and Beanie, who were standing in for Nick and Finn, who apparently were still at the beach although they had each been texted and called forty times in the past hour, then the other twin and Margot. Then Kevin and Beanie’s youngest son, Brock, as the ring bearer, alongside Ellie, the flower girl.

Ellie was still in her bathing suit. Doug, who made a point never to interfere with his kids’ parenting, had said to Margot, “Really? You brought her to church in a bathing suit?”

Margot had instantly gotten her hackles up, as Doug expected.

“I’m doing the best I can, Dad,” she said. “She refused to change. I think it’s a reaction to the D-I-V-O-R-C-E.”

Really? Doug thought. Margot and Drum Sr. had been divorced for nearly two years. That sounded suspiciously like an excuse.

Roger, the wedding planner, was the director of this particular pomp and circumstance, despite the presence of the pastor of St. Paul’s and their pastor from home, Reverend Marlowe, who were co-officiating. Roger had his clipboard and a number two pencil behind his ear; he was wearing a pair of khaki shorts, Tevas, and a T-shirt from Santos Rubbish Removal. Doug had an affinity for this fellow Roger that bordered on the fraternal. He appreciated that sense and order and logic were prevailing in the planning of this nuptial fete. Whatever Doug was paying the guy, it wasn’t enough.

Roger had an old-fashioned tape recorder that was playing Pachelbel’s Canon; tomorrow there would be two violinists and a cellist. Pachelbel’s Canon was a piece of music Beth had loved even more than Eric Clapton or Traffic. She had loved it so much that she had asked Doug to play it over and over again in the days before she died. It would ease her passage, she said. Naturally, it was also the piece she had suggested for the processional, not realizing that as Doug stood, linked arm in arm with his youngest child, he would be suffused with the memory of sitting at Beth’s bedside, helplessly watching her die.

Tears stung Doug’s eyes, and he pinched the bridge of his nose. He took a few deep breaths. Next to him, looking as soft and lovely as a rose petal, Jenna said, “Oh, Daddy,” and from some unseen place, she pulled a pressed white handkerchief.

That did it: Doug started to cry. It was all too much-giving his baby girl away, the confusion about Pauline, and his longing for Beth. She should be here. She should be here, goddamn it! In the seven years since her death, he had missed her desperately, but never as much as he did right this instant. Her absence physically pained him. He realized then that he had forgotten to read the last page of the Notebook, although he had decided, while overlooking the eleventh green at Sankaty, that today would be the day to do so. Now he was glad he hadn’t read it. He couldn’t handle it.

Doug blotted his face with the handkerchief, mopping up the tears that were now flowing freely. He caught Roger looking at him with concern. Doug didn’t have an issue with grown men crying; he saw it week in and week out at his office-a college president had cried, an orthopedic surgeon had cried, a famous TV chef had cried. The loss of love could undo anyone.

And so, when the music switched to Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary and he and Jenna took their first matched steps down the aisle, everyone who rose saw him weeping.

He didn’t try to stop himself. Beth, he thought. Beth, look at our baby.

Because it was the rehearsal, the only people in attendance were the wedding party and, seated in the front pew, Pauline, and Stuart’s parents, Ann and Jim Graham. Doug figured he might as well get all the tender thoughts out of the way now; that way tomorrow he might have half a chance of remaining composed.

He allowed himself to remember the first moment that Jenna was placed in his arms. She had been the smallest of the four children at birth-a mere six pounds, twelve ounces-and she fit comfortably in both his upturned palms. He remembered her eyes, round and blue, and her head covered with baby chick fuzz.

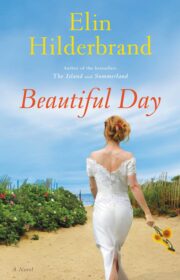

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.