“I don’t know about this, Marge,” he said. “Marge” was his nickname for her, bestowed in 1989 with the first season of The Simpsons, and Margot detested it, which only made Nick’s enjoyment of it more profound. “This is Alfie we’re talking about. This tree should probably be listed in the historic registry. It’s two hundred years old.”

“I know,” Margot snapped. She was impatient with Nick and everyone else who was lagging behind; she had traveled this emotional highway yesterday. “It’s just one branch! There’s no other way, believe me.”

Ellie sobbed into Margot’s leg. Margot watched Nick pick the swing up off the ground and loop the rope around his arm. The plank of the swing was worn smooth. Margot was forty years old, and the swing had been there as long as she could remember. Who had put it up? She thought it might have been Pop-Pop; she would have to ask her father. Forty percent chance of showers, she thought. There was no doubt in Margot’s mind that now, because the branch was coming down, there wouldn’t be a cloud in the sky all day tomorrow.

Hector and his associates indicated that they should all back up even farther. He set up a stepladder, and one of the other guys brought out the chain saw.

“I can’t watch,” Jenna said.

It did seem morbid, all of them standing around, gawking like witnesses at an execution. Margot reminded herself that it could be worse. Alfie might have been struck by lightning. As it was, he would still stand guard over their property, still shade them; birds would still sing from their unseen perches in his upper branches. They were only taking off one limb-and Roger was right, that branch was hanging awfully low. It might have snapped on its own with the next nor’easter.

There was a honking, and Margot turned to see a silver minivan pull into the driveway.

“It’s Kevin!” Jenna said. “Oh, thank God!”

Margot made a face. Their whole lives it had always been “Thank God for Kevin.” Kevin was eleven months younger than Margot-an oops baby, Margot was certain, although neither of her parents had ever admitted to it-but because Kevin was a boy, he had often been treated as the oldest. And to boot, he had been born with the unflappable calm and unquestioned authority of an elder statesman. He had been class president all through high school, then had attended Penn, where he’d been the head of the Student Society of Engineers. While in college, he had performed CPR on a man who collapsed on the Thirtieth Street subway platform, and he’d saved the man’s life. Kevin had been awarded a medal by the mayor of Philadelphia, Ed Rendell. Kevin Carmichael was, literally, a lifesaver.

He unfolded himself from the minivan-he had no shame about driving the thing, despite ruthless teasing from both Margot and Nick-and stood, all six feet six of him, in the sun, grinning at them.

“We’re here!” he said. “The party can start!”

Beanie materialized at his side, all five foot two of her, and slid her arm around Kevin’s middle so that the two of them could be frozen in everyone’s mind for a second, posed like a photograph captioned “Happily Married Couple,” before the three boys busted out of the back of the car and all hell broke loose.

Kevin strode forward, shielding his eyes from the sun as he gazed at the tree and the stepladder and Hector with the chain saw. “What’s going on here?” he asked.

God, his tone drove Margot insane. Was it normal, she wondered, to have your siblings grate on you like this? As much as she was dreading the amputation of Alfie’s branch, she now wished it had already happened, just so she didn’t have to stand by and watch Kevin weigh in on it. Kevin was both an architect and a mechanical engineer; he had founded a company that fixed structural problems in large buildings, important buildings-like the Coit Tower in San Francisco. Like the White House.

“They have to cut that branch,” Margot said. “Otherwise the tent can’t go up.”

Kevin eyed the branch, then the upper branches of the tree, then the yard as a whole. “Really?” he said.

“Really,” Margot said.

At that moment Roger appeared, holding his clipboard; Margot hadn’t heard his truck, so he must have parked on the street. Plus, that was Roger’s way: he appeared, like a genie, when you most needed him. He could explain to Kevin about the branch.

Margot turned her attention to Beanie and gave her sister-in-law a hug. Beanie had looked exactly the same since she was fourteen years old, when she and her family moved to Darien from the horse country of Virginia. Her brown hair was in a messy bun, her face was an explosion of freckles, and she wore horn-rimmed glasses. She never aged, never changed; her clothes were straight out of the 1983 L.L. Bean catalog-today, a white polo shirt with the collar flipped up, a madras A-line skirt, and a pair of well-worn boat shoes.

Beanie had probably worn this very same outfit on her first date with Kevin in the ninth grade. He had taken her to see Dead Poets Society.

Beanie said, “You look great, Margot.”

Beanie was a true golden good person. It was her MO to start every conversation with a compliment. Margot adored this about Beanie, even as she knew the compliment to be a lie. She did not look great.

“I look like a dirt sandwich,” Margot said.

“Last night was fun?” Beanie said.

Margot raised her eyebrows. “Fun, fun!” she said. She thought briefly of her sunken phone, Edge’s lost texts, and the reappearance of Griff. Oh, man. It was quite a story, but Margot couldn’t confide it to anybody, not even Beanie.

The Carmichael boys-Brandon, Brian, and Brock-were racing around the yard, chasing and tackling Drum Jr. and Carson. Ellie was perched above the fray on her uncle Nick’s shoulders. Nick came over to kiss Beanie, and Margot turned her attention to Roger and Kevin, who were deep in conversation. Then Kevin started speaking to Hector in fluent Spanish-what a show-off!-and pointing up at the tree branches.

Roger came over to Margot with an actual smile on his face, and Margot shivered, despite the warm sun. She had never seen Roger smile before.

“Your brother has an idea,” Roger said.

Margot nodded, pressing her lips together. Of course he does, she thought.

“He thinks we can lift the branch with a series of ropes that we would tie to the upper branches,” Roger said. “He thinks we can lift it enough to clear the height of the tent.”

“How is he planning on reaching the upper branches?” Margot asked. The upper branches were high, a lot higher than Kevin standing on top of the ladder.

“I have a friend with a cherry picker,” Roger said.

Of course you do, Margot thought.

“I’m going to call him right now,” Roger said. “See if he can come over.”

“Will a cherry picker fit through here?” Margot asked. Alfie dominated the eastern half of the backyard. Beyond Alfie was Beth Carmichael’s perennial bed and the white fence that separated them from the Finleys’ next door. Any kind of big truck would mow right over the flower bed. “My mother was very clear that no one was to trample her blue hardy geraniums.”

But Roger was no longer listening. He was on his phone.

“Isn’t it great?” Jenna said. “Kevin found a way to fix it! We don’t have to cut Alfie’s branch.”

“Maybe,” Margot said. She wondered why she didn’t feel happier about this breakthrough news. Probably because it had been Kevin who came up with the answer. Probably because she now looked like a knee-jerk tree-limb amputator who would have lopped off a piece of Carmichael family history if Kevin hadn’t arrived in time to save the day.

Margot smiled. “Thank God for Kevin,” she said.

She knew she sounded like sour grapes, and Jenna kindly ignored her.

Margot heard the back screen door slam, and she turned, expecting to see Finn or Autumn emerging-but the person who came through the door was her father. And behind her father, Pauline.

“Daddy!” Margot said.

Doug Carmichael was dressed in green golf pants and a pale pink polo shirt and the belt that Beth had needlepointed for him over the course of an entire summer at Cisco Beach. The outfit said “professional man ready for a day of good lies and fast greens,” but his face said something else.

For the first time in her life, Margot thought, her father looked old. He was a tall, lean man, bald except for a tonsure of silver hair, but today his shoulders were sloping forward, and his hair looked nearly white. His face held the same hangdog expression that he’d worn for the two years after Beth died, and it broke Margot’s heart to see it now.

As he approached, Margot held her arms out for a hug, and they embraced, and Margot squeezed extra hard. He still felt solid and strong, thank God.

“Hi, sweetie,” he said.

“You made it,” Margot said. “Is everything okay?”

He didn’t answer. He couldn’t, he had to move on to Beanie and Nick-and Jenna, whom he picked clear off the ground. Margot felt a crotchety old jealousy. How many times had she wished that she was the little sister instead of the big sister, the youngest instead of the oldest? She never got coddled; she never got picked up. Jenna was the Carmichaels’ answer to Franny Glass, Amy March, Tracy Partridge. She was the doll and the princess. Margot used to comfort herself with the knowledge that she had been their mother’s confidante, her right hand. In the weeks before Beth died, before things got really bad and hospice and morphine were involved, she had said to Margot, “You’ll have to take care of things, honey. This family will need to lean on you.”

Margot had promised she would take care of things. And she had, hadn’t she?

“Hello, Margot.”

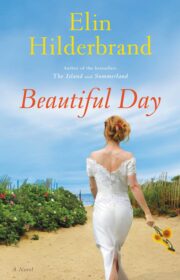

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.