She dialed the number; she had called it so often during the past few months that she had it memorized. It was late, she knew, but this couldn’t wait.

He picked up on the second ring. Of course he did.

“This is Roger.”

“Roger, Margot Carmichael,” she said. “The branch has to come down.”

“Yes,” he said. “I know it does. I’ve been waiting for you to call.”

“You have?” Margot said.

“You’re doing the right thing,” Roger said. “There is no other way.”

“No other way,” Margot repeated. “You’re sure?”

“I’ll see you bright and early,” Roger said.

OUTTAKES

Jim Graham (father of the groom): I am a man who has lived and learned. I married the right woman, but I didn’t know it, I married the wrong woman and I did know it, I married the right woman a second time. My advice to all four of my sons has been “Look before you leap.” This may be a cliché, but as with most clichés, it contains a hard kernel of truth. I like to think that advice was what kept Stuart from making a mistake several years ago. But he’s got the right idea now. Jenna is a beautiful girl and she brings out his best self. Really, what more can you ask?

H.W. (brother of the groom, groomsman): Open bar all weekend long.

Ann Graham (mother of the groom): I was born and raised in Alexandria, Virginia, I attended Duke University, I have served in the North Carolina General Assembly for twenty-four years. When Jim and I take vacations, we go to Savannah or the Outer Banks or Destin. Once to London, once on a cruise in the Greek islands. But I can’t tell you the last time I crossed the Mason-Dixon Line. It might have been New York City, 2001, when Jim and I went to the funeral of one of his fraternity brothers who worked for Cantor Fitzgerald. It will be nice to head north this time for a happier occasion.

Jethro Arthur (boyfriend of the best man): Unlike Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket is no place for a black man. I told this to Ryan and his response was that Frederick Douglass spoke on the steps of the Nantucket Atheneum in 1841. Frederick Douglass? I said. That’s what you’ve got? Yes, he said. And you know who else spent time on Nantucket? Who? I said. Pip and Daggoo, he said. Pip and Daggoo? I said. You mean the characters from Moby-Dick? Yes! he said, all proud and excited, because literary references are usually my territory. I said, Pip and Daggoo are fictional black men, Ryan. They don’t count.

FRIDAY

ANN

There were only a few ills in life that a five-star hotel on a bright, sunny day couldn’t fix. This was what Ann Graham told herself at ten o’clock on Friday morning when she and Jim arrived at the White Elephant resort on Nantucket Island. Ann had personally seen to it that they would be able to check in right away; nothing would have driven her battier than having to sit around-possibly for hours-waiting for their room to be ready. And so, less than thirty minutes after arriving on Nantucket, Ann was standing on the balcony of their suite, overlooking the harbor, which was as picturesque as she had imagined. The sailboats, the ropes, the bobbing red and white buoys, the two blond teenagers in a rowboat with fishing poles, the lighthouse on the point. This was the real thing. This was East-Coast-Yankee-blue-blood-privilege-and-elitism at its very finest.

Jim came up behind her and placed his hands on her shoulders. “Should we order up champagne and get naked?”

Ann willed herself not to shrug him off. He was being funny; he wanted her to relax. He did not want her to become the woman she was dangerously close to becoming: a woman who alternately expressed bitterness and hysteria because her son was getting married in a place where she exerted no influence.

The groom’s side of the family, Ann had learned over the past thirteen months, were second-class citizens when it came to the planning and execution of the wedding ritual in America. Maybe it was different in some far-flung tribe in Papua New Guinea or Zambia, and if so, Ann would gladly move there. She was the mother of three sons. She would have to endure this humbling social position at least twice-with Stuart now, and later with H.W. She had no idea what would happen with Ryan.

She and Jim weren’t even throwing the rehearsal dinner, which it was customary, in the wedding ritual in America, for the groom’s parents to do. Jenna had insisted on holding the rehearsal dinner at the Nantucket Yacht Club-apparently this was a suggestion drawn straight from the blueprints her deceased mother had left behind. The Carmichaels had been members of the yacht club since forever; Ann and Jim couldn’t have paid if they’d wanted to. They had, initially, offered to do just that, however-Doug Carmichael could let the Grahams know the cost of the yacht club party, and Jim would write Doug a check to cover it. Doug had graciously refused the offer, and Ann was glad, not because of the expense-she and Jim could easily have afforded it-but because if Ann was going to host a party, she wanted to put her stamp on it. She wanted to pick the location and the flowers and the menu. If the rehearsal dinner had to be held at the Carmichaels’ club, she agreed that the Carmichaels should pay. After Ann’s insistence that she and Jim do something, Jenna had suggested that the Grahams host the Sunday brunch. This felt like a consolation prize to Ann. The Sunday brunch? Half the guests would skip the damn thing because of early departing flights or boats, and the other half would show up exhausted and hung over. Ann nearly rejected the Sunday brunch idea, but then she realized that doing so would make her seem like a spoiled child who hadn’t gotten her way, rather than the six-term North Carolina state senator, devout Catholic, and mother of three that she was. So she said yes and made up her mind that the Sunday brunch was going to be the best part of the whole weekend. Ann had arranged for the White Elephant to set up a tent on the lawn facing the water, and under this tent would be a little piece of the Tar Heel State. The menu would include barbecue flown in from Bullock’s in Durham, as well as two kinds of grits, hush puppies, collard greens, coleslaw, buttermilk biscuits, and pecan pie. Ann had asked the head bartender at the White Elephant, a guy named Beau who actually hailed from Charleston and had worked at Husk, to make ten gallons of sweet tea and order Kentucky bourbon for juleps and whiskey sours. Ann had hired a Dixieland band, who would wear straw boaters and candy-striped vests. They would show Stuart’s new family some genteel southern hospitality.

Still, Ann felt like the runner-up in this particular beauty pageant, and it brought out the worst in her-much the way a nasty campaign did. During her third term, when the scandal with Jim was breaking at home, Ann had battled against the reprehensible Donald Morganblue. She had been sure she was going to lose. The race was close, Morganblue had gone after Ann about a certain failed development project near Northgate Park that had cost Durham County millions of dollars and nearly five hundred promised jobs, and Ann had spent a string of months convinced that both her personal life and her professional life were going to go up in flames. She had, very nearly, become addicted to Quaaludes. The pills were the only way she had made it through that period in her life-the victory by the narrowest margin in the state history of the Carolinas (requiring two recounts) and her divorce from Jim. Ann remembered how the pills had made her feel like a dragonfly skimming over the surface of these troubles. She remembered more than one occasion when she had held the pill bottle in her sweating palm and visualized an easy descent into sweet eternity.

She told herself now that she had never seriously considered suicide back then. Stuart had been ten years old, the twins barely six, Jim had moved to the loft in Brightleaf Square; the boys needed Ann to pack their lunches and transport them to the Little League fields. At night that year, Ann had read the boys Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Their addiction to that book (at the kids’ behest, Ann had ended up reading it three times in a row) was the only outward reaction they had to their father’s departure. Or possibly they were addicted to the quiet minutes with her, curled up on the sofa, her voice always evenly modulated despite her inner turmoil.

There could be no killing herself. Plus, Ann was Catholic, and suicide was a sin for which there was no repenting.

Every once in a while, however, she still yearned for a Quaalude.

Now, for instance. She could use one right now.

She let Jim kiss the side of her neck, a move that always preceded sex. What if they did just as he suggested? What if they ordered up champagne, and strawberries and cream? What if they slipped on the white waffled robes and tore open the scrumptious bed and laid across the ten-thousand-count sheets and enjoyed each other’s bodies? Even now, fifteen years after their reconciliation, Jim’s sexual attention felt precious, like something that could be, and had been, stolen away from her. What if they drank champagne-the more expensive, the better-then ordered another bottle? What if they found themselves giddily drunk by noon, then fell into a languorous sleep with the balcony doors open, sunlight streaming over them in bed? What if they treated this not like their eldest son’s wedding weekend but like a romantic getaway?

“Let’s do it,” Ann said, pivoting to kiss her husband full on the lips. “Call for the champagne.”

“Really?” he said, his eyebrows lifting. He was fifty-six years old, a senior vice president at GlaxoSmithKline but just under the surface was the boy Ann had first married-president of Beta at Duke, the ultimate bad boy, for whom fun would trump responsibility whenever possible.

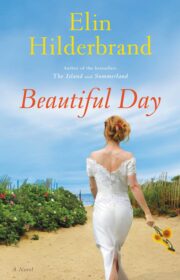

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.