And she had said, Moi?

Two Saturdays later, when Edge was back to pick up Audrey, they made plans to have coffee. A few days after the coffee date, they met for drinks, and drinks had turned into the two of them making out on a dark street corner in Hell’s Kitchen. Edge had said, “Your father would kill me if he saw us now.”

And Margot said, “My father will never find out.”

Those had been the words that they’d lived by; those had become the chains that strangled their relationship, made it clunky, and kept it from growing. Doug could never find out.

“Whatever,” Margot said now. “It’s kind of a mess.”

“Is he coming to the wedding?” Rhonda asked.

“Yes,” Margot said. “Tomorrow.”

“Well, then, we still have tonight,” Autumn said. “Let’s get out of here.”

That’s a beautiful girl you’ve got there, partner. Those eyes. Margot had asked Edge if he remembered saying that.

He had shaken his head, baffled. No, he said.

Margot flagged the bartender for the check. “This is my treat,” she said.

“Oh, Margot, come on,” Autumn said. “It’s too much.”

“I insist,” Margot said, and she could tell Autumn felt relieved.

“Thank you!” Rhonda said. “That’s really generous.”

Margot looked at Rhonda. Rhonda’s face was fresh, smiling, sincere. This was the same woman who had once told Margot she bought dresses at Bergdorf’s, wore them with the tags on, and returned them the next day?

“You’re welcome,” Margot said. She was done trying to predict what would happen next. This wedding had taken on a life of its own.

THE NOTEBOOK, PAGE 9

The Service

Religion is tricky. Think of Charlemagne and Martin Luther and the Spanish Inquisition and the Gaza Strip. I don’t know if you’ll marry a man who is Muslim or Jewish or a happy agnostic, and I will tell you here that I don’t care what religion your Intelligent, Sensitive Groom-to-Be practices, as long as he is good to you and loves you with the proper ardor.

I am going to proceed with this portion of the program as though you will be married at St. Paul’s Episcopal. I fell in love with St. Paul’s the first time I passed it on Fair Street, and I convinced your father to attend Evensong services one summer night in June. Who wouldn’t love Evensong in a church with that glorious pipe organ and those Tiffany windows?

I have been to weddings where the officiant didn’t know the couple getting married, and he was therefore forced to deliver a canned sermon. For this reason, I suggest you ask Reverend Marlowe to come to Nantucket to perform the service. Harvey is a sedentary being, and he won’t like the idea of traveling to an island thirty miles offshore. But ask him anyway. Beseech him. He has never been able to resist you, his little Jenna who went on the Habitat for Humanity trip to Guatemala at the tender age of fifteen. I think he believed you would grow up to be a missionary. You single-handedly changed his mind about the Carmichael family-you (nearly) made him forget that it was Nick who set off a smoke bomb in the church basement during coffee and doughnut hour.

Reverend Marlowe is fond of his creature comforts, so be sure to mention that your father will fly him to the island and pay for a harbor view room at the White Elephant, where a bottle of fifteen-year Oban will be waiting for him.

But the Scotch and the turndown service are just window dressing. Reverend Marlowe would do anything for you.

DOUGLAS

He drove to Post Road Pizza, which was a place he used to go with Beth. He asked to sit at the two-person booth in the front window, which was where they always sat. He ordered a draft beer, a pizza with sausage and mushrooms, and a side order of onion rings with ranch dressing for dipping, which was what he and Beth always used to order. Doug took a couple of swills off his beer and walked over to the jukebox. It still took quarters. He dropped seventy-five cents into the jukebox and played “Born to Run,” “The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys,” and “Layla.” These were all Beth’s favorite songs; she had been fond of the rock anthem. If Doug asked Pauline to name one song by Eric Clapton or Bruce Springsteen, she would be stumped.

There had been a time-six, seven years ago, right after Beth died-when Doug had come into this pizza place and ordered this food and played these songs and occupied this booth as a way of wallowing in his misery. Now, he felt, he was doing it as a show of strength. This was who he really was-he liked this restaurant, he loved these songs, he preferred a cold draft beer to even the finest chardonnay. When the waiter brought his food, he thought with enormous satisfaction: Not a fresh vegetable in sight! Pauline would look upon the onion rings with disgust. When he dragged the golden circles through the ranch dressing, she would say, “Fat and more fat.” Secretly, she would be dying to take one-but she wouldn’t, because she was obsessed with calories. The only way she felt in control was when she was depriving herself. And that was the reason, or part of the reason, why she had become so miserable.

Doug lifted a piece of pizza, and the cheese stretched out into strings. He gloried in the fact that he was not at home eating lamb chops.

In his back pocket, his phone was buzzing away. Pauline, Pauline, Pauline. She didn’t know how to text, and so she would just call and call, leaving increasingly hysterical messages until he answered. He imagined her stumbling around the house, bouncing off the furniture, drinking chardonnay, calling Rhonda-who, by this time, would be on Nantucket-saying the rosary or a Hail Mary or whatever Catholic ditty was supposed to fix the things that went wrong. Sometimes, when things were really bad with Rhonda or her ex-husband, Arthur, Pauline would tell Doug that she was going upstairs to “take a pill.” Doug didn’t know what pills those were; he had never asked because he didn’t care, but he hoped now, anyway, that she would take a pill, just so she would stop calling.

He could practically see Beth in the seat across from him-wearing one of her sundresses, her hair long and loose, with a little hippie braid woven into the side. She had liked to wear the braid to let the world know that although she was married to a hotshot lawyer and worked as a hospital administrator and was the mother of four children and lived in a center-entrance colonial on the Post Road in a wealthy Connecticut suburb, she still identified with Joni Mitchell and Stevie Nicks, she was a Democrat, she read Ken Kesey, she had a social conscience.

Beth, he asked. How did I end up here?

Beth had left the Notebook for Jenna, but she hadn’t left any instruction manual for him. And oh, how he needed one. When Beth died, he had been lost. The older three kids were all out of the house, and Jenna had stayed with him for a few weeks, but then she had to go back to college. He only had to take care of himself; however, even that had proved challenging. He had buried himself in work, he stayed at the office for ridiculously long hours, sometimes longer than the associates who were trying to make partner. He ordered food in from Bar Americain or the Indian place down the street, he kept a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black in his locked drawer, he didn’t exercise, didn’t see the sun, and he dreaded nothing more than the weekends when he had no choice but to return to his house in Darien and the bedroom he had shared with Beth, and the well-meaning neighbors who drove by, wondering when he was going to call the landscapers.

He had loved her so much. Because of his line of work-day in, day out, divorce, divorce, divorce-he knew that his union with Beth was a rare and precious thing, and he had treated it as such. He had revered her; she always knew how much he loved her, at least he could say that. But that assurance didn’t fill the hole. It couldn’t mend the ragged edges of his loneliness. Nothing helped but the oblivion that work and whiskey provided.

To this day, he wasn’t sure how Pauline had gotten through to him. Probably, like everything else in life, it was a matter of timing. Pauline had come to see him eighteen months after Beth’s death, when the acute pain was subsiding and his profound loneliness was deepening. He had gained thirty pounds; he was drinking way too much. When Margot paid an unannounced visit to Darien and saw the state of his refrigerator (empty), his recycling bin (filled with empty bottles), and his house (an utter and disgusting mess), she had a fit. She said, “Jesus, Daddy, you have to do something about this!” But Doug didn’t know what that something was. He was proud that he managed to get his shirts and suits back and forth from the dry cleaners.

At first, Pauline Tonelli had been just another fifty-something woman who had been married for decades and was now on the verge of becoming single. Doug had seen hundreds of such women. He had been hit on-subtly and not so subtly-by clients for the entirety of his career. Being propositioned was an occupational hazard. Every woman Doug represented was either sick of her husband or had been summarily ditched by him (often in favor of someone younger), and most, in both cases, were ready for someone new. Many women felt Doug should be that man. After all, he was the one now taking care of things. He was going to get her a good settlement, money, custody, the yacht club membership, the second home in Beaver Creek. He was going to stand up in court on her behalf and fight for her honor.

Doug knew other divorce attorneys who took advantage of their clients in this way. His partner-John Edgar Desvesnes III-Edge, had taken advantage of at least one woman in this way: his second wife, Nathalie, whom he had fooled around with in the office before she had even filed, then dated, then married, then procreated with (one son, Casey, age fifteen), then divorced. There were still other attorneys who, it was rumored, were serial screwers-of-clients. But Doug had never succumbed to the temptation. Why would he? He had Beth.

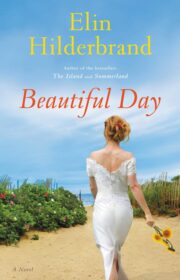

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.