She checked her phone. Nothing from Edge. What was wrong with him? Margot was tempted to text, Is everything okay? But that might come across as sounding nagging or needy-or worst of all, wifely. Another problem with texting: it was nearly impossible to express tone. Margot wanted to let him know that she was concerned without having him think she was asking, Why the hell aren’t you texting me back? Which was, of course, exactly what she was asking.

There was a text on her phone from Rhonda. Margot opened it eagerly, expecting more drama. It said: My plane arrives at 8:20. What time dinner?

Margot deflated a bit. It sounded like Rhonda was still coming. This was bad. This was, in so many ways, the worst-case scenario. To have Rhonda, but no Pauline? Unthinkable. Who would Rhonda talk to, who would Rhonda hang out with, if not Pauline? There were no other Tonellis coming to the wedding, and none of Pauline’s friends.

Margot typed back: Dinner is at 8.

Rhonda responded right away: Who picking me up? Rhonda always, in Margot’s experience, responded right away because-Margot suspected-Rhonda had nothing to do but text back right away. She had no proper job, no other friends.

Margot typed: Pls take a cab.

Rhonda replied: ?

Margot looked at the question mark, then burst out laughing. Of course Rhonda had texted a question mark. She was probably wondering why Mr. Roarke wasn’t picking her up in a white stretch limo.

Margot had sent a handful of detailed e-mails about tonight’s bachelorette party to all involved. She had listed the name and address of the restaurant and the time of their dinner reservation-8:00-in each message. That Rhonda had then booked a flight that landed at 8:20 wasn’t Margot’s problem.

Was it?

Guilt.

But no, there wasn’t time.

Although Jenna’s bedroom was the smallest-the “spinster aunt bedroom,” their mother had always called it, since for decades it had belonged to Doug’s spinster aunt, Lucretia-it was also the best appointed because it had a deck that overlooked the backyard and the harbor. It was on this deck that Margot and the other maidens opened the champagne.

Autumn took charge of popping the cork, since she waited tables at a beachfront seafood restaurant in Murrells Inlet, South Carolina. The cork sailed into the yard, and Margot watched Jenna’s eyes follow it as it landed in the grass.

Then Jenna said, “I guess I thought the tent would be bigger.”

Autumn expertly filled four glasses, and Margot reached for one. She wanted to drink the whole thing down in one gulp, but she had to make a toast. She smiled at Jenna, and Jenna smiled back. Jenna wouldn’t care about the tent or about Margot making a unilateral decision about Alfie’s tree branch. All Jenna cared about was Stuart, who would be arriving tomorrow with his people.

“To an amazing, wonderful… and sunny weekend!” Margot said.

The four of them clinked glasses.

Jenna said, “There is another tent going up, right? The one the people are sitting under?”

“Yes,” Margot said. Drink drink drink. “Tomorrow.”

“Oh,” Jenna said. “I thought it was going up today.”

“Nope,” Margot said. Drink drink drink. “It’s tomorrow.”

Jenna frowned. Margot thought maybe the issue would explode right then and there. Instead Jenna said, “I miss Stuart.”

Finn was frowning also. She said, “At least he’s not in Vegas, getting a lap dance.”

Margot recalled Finn’s expression on the ferry when Scott’s name came up. So that was why: Vegas, lap dances, strip clubs, cocktail waitresses with large, enticing fake breasts. Margot remembered how things like that could seem threatening to a new marriage. But that kind of jealous anxiety faded away, just like everything else. At the end with Drum Sr., Margot had found herself thinking, Why don’t you go to Vegas and get a lap dance?

Autumn said, “Lap dances are harmless. I get them all the time.”

For the first time all day, something struck Margot as funny. “You get lap dances?”

“Yeah,” Autumn said. “Guys love it.”

“Oh,” Margot said. She wondered for an instant if Edge would love it if she, Margot, got a lap dance. She decided he most definitely would not.

Autumn filled her glass with more champagne, and Margot watched the golden liquid bubble to the top. The kids were playing Frisbee with Emma in the yard below. Margot remembered when it had been she and her siblings playing in the yard, while her parents drank gin and tonics on this deck and turned up Van Morrison on the radio. Her mother used to wear a blue paisley patio dress. Margot would hug Alfie’s trunk, her arms not even reaching a third of the way around. A tree wasn’t a person, but if a tree could be a person, then Alfie would be a wise, generous, all-seeing, godlike person. She couldn’t let the tent guys cut the branch. The cut would be a wound; it might get infected with some kind of mung. Alfie might die.

Margot stood up and leaned over the railing. She felt dizzy. She felt like she might drop.

“We should go,” she said.

Jenna was driving.

They bounced across the cobblestones at the top of Main Street. Town was teeming with people who had come to Nantucket to celebrate summer. Margot loved the art galleries and shops, she loved the couple carrying a bottle of wine to dinner at Black-Eyed Susan’s, she loved the dreadlocked guy in khaki cargo shorts walking a black lab. She noticed people noticing them-four pretty women all dressed up in Margot’s Land Rover. Jenna and Finn were wearing black dresses, and Autumn was wearing green. Margot was wearing a white silk sheath with a cascade of ruffles above the knee. She loved white in the summertime. The city was too dirty to wear white-one cab ride and this dress would be trashed.

Jenna took a right onto Broad Street, past Nantucket Bookworks and the Brotherhood and Le Languedoc, and then a left by the Nantucket Yacht Club. Margot tapped her finger on the window and said, “That’s where we’ll be tomorrow night!”

No one responded. Margot turned around to see Finn and Autumn pecking away at their phones. Then Margot looked at Jenna, who was skillfully navigating the streets, despite that fact that pedestrians were crossing in front of them without looking. Margot felt bad that Jenna was driving to her own bachelorette party, but Jenna had insisted. Margot should have hired a car and driver, and then all four of them would be sitting in the backseat together. And Margot should have made a rule about no cell phones. What was it about life now? The people who weren’t present always seemed to be more important than the people who were.

Margot picked her clutch purse off the floor of the car and, against her better judgment, checked her phone. She had one text, from Ellie. I miss you mommy.

Margot decided not to be disappointed that her only text was from her daughter, and she decided not to be horrified that her six-year-old knew how to text. Margot decided to be happy that someone, somewhere in the world, missed her.

When she looked up, Jenna was pulling into the restaurant parking lot. Margot knew this was the time to muster her enthusiasm and rally the troops. The group was low-energy; even Margot herself was flagging. A glass and a half of champagne might as well have been three Ambien and a shot of NyQuil. If Jenna turned the car around, Margot would happily sleep until morning.

But she was the maid of honor. She had to do this for Jenna.

And her mother.

The Galley was a bewitching restaurant. It was the only fine dining on Nantucket located on the beach. Most of the seating was under an awning with open sides bordered by planters filled with red and pink geraniums. There were divans and papasan chairs and tiki torches out in the sand. There was a zinc bar. The crowd was buzzing and beautiful. Over the years, Margot had seen an assortment of powerful and famous people at these tables: Martha Stewart, Madonna, Dustin Hoffman, Ted Kennedy, Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones, Robert DeNiro. The Galley was see and be seen. It was, always, on any given night, the place to be.

They were seated at a table for four in the main dining room, but in the part of the room that was closer to the parking lot. Autumn didn’t sit down right away; she was scanning the surroundings. Finally, she settled in her chair. She said, “I think we should ask for a better table.”

Margot felt something sinking and rising in her at the same time. Spirits sinking, ire rising. She said, “A better table, where? This place is packed!”

“Out in the sand, maybe,” Autumn said. “Where there’s more action.”

Margot couldn’t believe this. She’d had a hell of a time even getting this reservation for eight o’clock on a Thursday night in July. She had called on the Tuesday after Memorial Day and had been told, initially, that the restaurant was booked, but her name could be added to the wait list. And now Autumn-the so-called restaurant professional-was complaining? Insinuating that Margot hadn’t been important or insistent enough to score a better table? It was Autumn’s fault that the bachelorette party was being held tonight, at the very last minute, instead of weeks or months earlier, which was more traditional. There were five people’s schedules to accommodate, and so Margot had put forth options, all of them enticing. A ski weekend in Stowe, or a spring weekend out at the spa in Canyon Ranch. But Autumn hadn’t been able to make either one. Weekends are really hard for me, she’d written.

Well, it was nearly impossible to plan a bachelorette party during the week, but Margot gave it a shot and threw together something in Boca Raton the week of Jenna’s spring break from Little Minds, but again Autumn couldn’t attend, so Margot canceled.

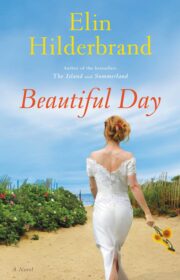

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.