She checked the weather for Saturday on her phone. This was the only thing she’d been more compulsive about than checking for texts from Edge. The forecast for Saturday was the same as it had been when she’d checked it from the ferry: partly cloudy skies, high of 77 degrees, chance of showers 40 percent.

Forty percent. It bugged Margot. Forty percent could not be ignored.

“Cut the branch,” she said.

Roger nodded succinctly and headed outside.

Margot had fifty million things to do, but unable to do any of them, she sat at the kitchen table. It was a rectangular table, made from soft pine. Along with everything else in the house, it had been abused by the Carmichaels. The surface held ding marks, streaks of pink Magic Marker, and a half-moon of black scorch that came from popcorn made in a pot on a night when Doug and Beth had been out to dinner at the Ships Inn and Margot had been left to babysit her siblings.

Margot remembered her mother being distraught about the scorch mark. “Oh, honey,” she’d said. “You should have used a trivet. Or put down a dish towel. That mark will never go away.”

At age fourteen, Margot had thought her mother was overreacting to make Margot feel bad. She had stomped up to her room.

But her mother had been right. Twenty-six years later, the scorch mark was still there. It made Margot wonder about permanence. She had just given the okay for the tent guys to amputate Alfie, a tree that had grown in that spot for over two hundred years. The tree had been there since colonial times; it had a majesty and a grace that made Margot want to bow down. The branch would never grow back; a tree wasn’t like a starfish, it didn’t regenerate new limbs. Margot wondered if twenty-five years from now she would walk her grandchildren out to that tree and show them the place where the branch had been sliced off and say, “We had to cut that branch down so we could put up a tent for my sister Jenna’s wedding.”

Generations of their descendants would go without a tree swing in the name of this decision.

Margot heard the whine of the chain saw. She covered her face with her hands.

Her mother hadn’t written anything about the tree swing in the notebook.

Cut Alfie’s branch? Margot asked her.

The sound of the chain saw raised goose bumps. It felt as if the guy was about to cut out Margot’s own heart.

She ran out the back door.

“Stop!” she cried.

The wedding was taking on a life of its own. It was the damnedest thing. A person could plan for months down to the tiniest detail, a person could hire someone like Roger and have a set of written blueprints such as their mother had left-and still things would go wrong. Still the unexpected would happen.

“I can’t let you do it,” Margot said to Roger. “I can’t let you cut it.”

“You understand this means no tent?” he said.

Margot nodded. No tent. Partly cloudy, 40 percent chance of showers. A hundred and fifty people, tens of thousands of dollars of tables, chairs, china, crystal, silver, floral arrangements, food, and wine-all with a 40 percent chance of getting drenched. Margot fretted as she thought about the antique, hand-embroidered table linens, most of which were the same linens Margot and Jenna’s grandmother had used for her wedding in this very same backyard in 1943. What if those linens got rained upon? (Their grandmother had hosted ninety-two guests at her wedding, under a striped canvas tent supported by wooden poles. Back in 1943, Alfie’s branches would have been younger, stronger, and higher.)

Margot knew she should confer with someone, get a second opinion: Jenna, or her father. But Margot felt that her primary duty as maid of honor was to shield Jenna from the treacherous obstacles that would pop up over the next seventy-two hours. On Sunday afternoon, as soon as the farewell brunch was over, Jenna would be on her own. She would have to face her life as Mrs. Stuart Graham. But until then, Margot was going to make the tough decisions. She might have called her father, but her father, obviously, had issues of his own.

Plus, Margot felt confident that no one in the Carmichael family-not Doug, not Jenna, not Nick or Kevin-would want to see that branch cut down.

“No tent,” Margot said.

“I’ll see about the smaller tent,” Roger said.

“Thank you,” Margot said. She paused. “I don’t expect you to understand.”

“Pray for sun,” Roger said.

Margot was staying in “her room,” sharing the double bed with Ellie, who was a flopper and a kicker. Drum Jr. and Carson would sleep in the attic bunk room with Kevin and Beanie’s three boys, and their uncle Nick-who, if he remained true to form, wouldn’t make it home to sleep at all. Jenna and Finn and Autumn were all cramming into Jenna’s room, which had one twin bed and one trundle bed; this was their choice, but it was also true that neither Finn nor Autumn had wanted to share with Rhonda, who had the proper guest room-with two double beds-all to herself. Kevin and Beanie would sleep in Kevin and Nick’s room (on the Eastlake twins), and Doug (but apparently not Pauline) would sleep in the master.

Margot hadn’t texted her father back yet because she didn’t know what to say, and she hoped that her silence would prompt more information.

She unpacked her suitcase and Ellie’s. Ellie had stuffed hers with trinkets, homemade bracelets, a ball of string, a stuffed inchworm that someone had brought to the hospital the day she was born, the tape measure from the junk drawer, an assortment of dried-out markers and broken crayons, and a tattered paperback copy of Caps for Sale. Ellie, Margot realized with weary concern, was becoming a hoarder. This was probably a result of the divorce, another thing for Margot to feel guilty about. She sat on the bed, letting the broken crayons sift through her fingers. Was it too early for wine?

In the way of clothes, Ellie had packed two mismatched socks, a white T-shirt with a grape juice stain down the front, a pair of turquoise denim overalls, her black-and-silver Christmas dress that she’d worn to The Nutcracker last year and had complained about the whole time, her favorite purple shorts with the green belt, and a seersucker sundress embroidered with lobsters that was two sizes too small. And hallelujah-a bathing suit. Margot should have checked Ellie’s packing job-really, who trusted a six-year-old to pack for herself?-but she’d been too busy. At least Margot had packed Ellie’s flower girl dress and her good white sandals in her own suitcase.

Margot hung up the white eyelet flower girl dress and then her own grasshopper green bridesmaid dress, thinking, God, I do not want to wear that.

But she would, of course, for Jenna. And for her mother.

Grocery store, liquor store. She was racing the clock, there was no time to think about Edge, or Drum Sr. getting married, or about Griff with his kaleidoscope eyes and the two days of growth on his face. But the three of them were in her brain. How to exorcise them?

She took an outdoor shower under the spray of pale pink climbing roses that her mother had cultivated and that still thrived. The roses alive, her mother dead. Was the fact that Margot didn’t like gardening a character flaw? Did it mean she wasn’t nurturing enough?

In the worst days of their divorce, Drum Sr. had accused Margot of being a coldhearted bitch. Was this true? If it was true, then why did Margot feel everything so keenly? Why did life constantly feel like being pierced by ten thousand tiny arrows?

She had been a coldhearted bitch to Griffin Wheatley, Homecoming King. He didn’t realize it, but it was true.

Guilt.

But no, there wasn’t time.

Margot fed her children a frozen pizza and grapes, serving them in her bathrobe, her hair still dripping wet.

Carson said, “Are you going out tonight?”

“Yes,” Margot said.

The three of them started to squeak, squeal, and whine in chorus. They hated it when Margot went out, they hated Kitty, their afternoon babysitter, they hated their afternoon activities regardless of what they were-because they sensed that these activities were also babysitters, substitutes for Margot’s time and attention. Margot had hoped that as they got older, they would come to see her career as one of the wonderful things about her. She was a partner at Miller-Sawtooth, where she did valuable work, matching up top executives with the right companies. She had a certain amount of power, and she made a lot of money.

But power and money meant little to her twelve-year-old and even less to the ten and the six. They wanted her warm body snuggled in the bed between them, reading Caps for Sale.

“It’s your auntie’s wedding,” Margot said. “A sitter named Emma is coming tonight and tomorrow night. Saturday is the wedding, and it will be held here in the backyard, and Sunday we’re going home.”

“Tonight and tomorrow night!” Drum Jr. said. Of the three of them, he was the one who needed Margot the most. Why this was, she couldn’t quite explain.

“Who’s Emma? I don’t know Emma!” Ellie said.

“She’s nice,” Margot said. “Nicer than me.”

It was nearly seven, and the light outside was still strong. The smaller tent had been raised, and now the guys were laying the dance floor. The grass would be matted, but Roger had assured them it wouldn’t die. The smaller tent looked good, Margot thought. It was bigger than she’d expected, but it wasn’t big enough to shelter 150 people. Maybe between the tent and the house. Maybe.

Forty percent chance of showers.

Emma Wilton showed up right at seven. She was a girl whom Margot used to babysit, now twenty-five years old and between years of veterinary school. She and Margot hugged, then remarked on how their relationship had circled around, and Margot said, “And ten or fifteen years from now, Ellie can babysit your kids.” They laughed, and Margot excused herself for the blow-dryer.

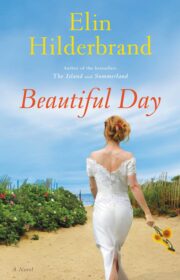

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.