“Serena!” Fanny cried, with a heightened colour. “How can you speak of Rotherham and Major Kirkby in the same breath?”

“Well, at least Rotherham never lectured me on the proprieties!” said Serena pettishly. “He doesn’t give a button for appearances either.”

“It is not to his credit! I know you don’t mean what you say when you put yourself into a passion, but to be comparing those two is outrageous—now, isn’t it? The one so arrogant, his temper harsh, his disposition tyrannical, his manners abrupt to the point of incivility; and the other so kind, so solicitous for your comfort, loving you so deeply—Oh, Serena, I beg your pardon, but I am quite shocked that you could talk so!”

“So I apprehend! There is indeed no comparison between them. My opinion of Rotherham you know well. But I must be allowed to give the devil his due, if you please, and credit him with one virtue! I collect you don’t count it a virtue! We won’t argue on that head. My scandalous carriage awaits me, and if we are not to aborder one another I’d best leave you, my dear!”

She went away, still simmering with vexation, a circumstance which caused her groom, a privileged person, to say that it was as well she was not driving her famous greys.

“Fobbing, hold your tongue!” she commanded angrily.

He paid no more attention to this than he had paid to the furies of a seven-year-old termagant, but delivered himself of a grumbling monologue, animadverting severely on her headstrong ways and faults of temper; recalling a great many discreditable incidents, embellished with what he had said to his lordship and what his lordship had said to him; and drawing a picture of himself as an ill-used and browbeaten serf, which must have made her laugh, had she been listening to a word he said.

Her rages were never sullen, and by the time she had discovered the peculiarities of her hired horses, this one had quite vanished. Remorse swiftly took its place, and the truth of Fanny’s words struck home to her. She saw again the Major’s face, as much hurt as mortified, remembered his long devotion, and without knowing that she spoke aloud, exclaimed: “Oh, I am the greatest beast in nature!”

“Now, that, my lady,” said her henchman, surprised and gratified, “I never said, nor wouldn’t. What I do say—and, mind, it’s what his lordship has told you time and again!—is that to be handling a high-spirited pair when you’re in one of your tantrums—”

“Are you scolding still?” interrupted Serena. “Well, if these commoners are your notion of a high-spirited pair, they are not mine!”

“No, my lady, and it wouldn’t make a bit of difference to you if they was prime ’uns on the fret!” said Fobbing, with asperity.

“It would make a great deal of difference to me,” she sighed. “I wonder who has my greys now?”

“Now, we don’t want to have a fit of the dismals!” he said gruffly. “If you was driving a pair of stumblers, you’d still take the shine out of any other lady on the road, my lady, that I will say! It’s time you was thinking of turning them, if you don’t want to be late back—them not being what you might call sixteen mile an hour tits.”

“Yes, we must go back,” she agreed.

He relapsed into silence, and she was free to pursue her own uncomfortable reflections. By the time they had reached Laura Place again, she had beaten herself into a state of repentance which had to find instant expression. Without pausing to divest herself of her hat or her driving coat, she hurried into the parlour behind the dining-room, stripping off her gloves, and saying over her shoulder to the butler: “I shall be wanting Thomas almost immediately, to deliver a letter for me in Lansdown Crescent.”

She was affixing a wafer to an impetuous and wildly scrawled apology when she heard the knocker on the front door. A few moments later, she heard the Major’s voice saying: “You need not announce me!” and sprang to her feet just as he came quickly into the room.

He was looking pale, and anxious. He shut the door with a backward thrust of his hand, and spoke her name, in a tense way that showed him to be labouring under strong emotion.

“Oh, Hector, I have been writing to you!” she cried.

He seemed to grow paler. “Writing to me! Serena, I beg of you—only listen to me!”

She went towards him, saying penitently: “I was odious! a wretch! Oh, pray forgive me!”

“Forgive you! I? Serena, my darling, I came to beg you to forgive me! That I should have presumed to criticize your actions! That I should—”

“No, no, I used you monstrously. Do not you beg my pardon! If you wish me not to drive my phaeton in Bath, I won’t! There! Am I forgiven?”

But this, she found, would not do for him at all. His remorse for having presumed to remonstrate with his goddess would be soothed by nothing less than her promising to do exactly as she chose upon all occasions. An attempt to joke him out of his mood of exaggerated self-blame failed to draw a smile from him; and the quarrel ended with his passionately kissing Serena’s hands, and engaging himself to drive out with her in the phaeton on the very next day.

11

The Major, reconciled to his goddess, could not be satisfied with setting her back on the pedestal he had built for her: the idealistic trend of his mind demanded that he should convince himself that she had never slipped from it. To have parted with the romantic vision he had himself created would have been so repugnant to him that the instant his vexation had abated, which it very swiftly did, he had set himself to prove to his own satisfaction that not her judgement but his had been faulty. It was impossible that the lady of his dreams could err. What had seemed to him intractability was constancy of purpose; her flouting of convention sprang from loftiness of mind; the levity, which had more than once shocked him, was a social mask concealing more serious thoughts. Even her flashes of impatience, and the dagger-look he had twice seen in her eyes, could be excused. Neither rose from any fault of temper: the one was merely the sign of nerves disordered by the shock of her father’s death; the other had been provoked by his own unwarrantable interference.

Not every difference that existed between imagination and reality could be explained away. The Major’s character was responsible; he had been an excellent regimental officer, steady in command, always careful of the welfare of his men, and ready to help junior officers seeking his advice in any of the private difficulties besetting young gentlemen fresh from school. His instinct was to serve and to protect, and it could not be other than disconcerting to him to find that the one being above all others whom he wished to guide, comfort, serve, and protect showed as little disposition to lean on him as to confide her anxieties to him. So far from seeking guidance, she was much more prone to impose her will upon her entire entourage. She was as accustomed to command as he, and, from having been motherless from an early age, she had acquired an unusual degree of independence. This, joined as it was to a deep-seated reserve, made the very thought of disclosing grief to another repellent to her. When she felt most she was at her most flippant; any attempt to lavish sympathy upon her made her stiffen, and interpose the shield of her raillery. As for needing protection, it was her boast that she was very well able to take care of herself; and when it came to serving her the chances were that she would say, gratefully, but with decision: “Thank you! You are a great deal too good to me—but, you know, I always like to attend to such things myself!”

He had not known it. Fanny, understanding his perplexity, tried to explain Serena to him. “Serena has so much strength of mind, Major Kirkby,” she said gently. “I think her mind is as strong as her body, and that is very strong indeed. It used to amaze me that I never saw her exhausted by all the things she would do, for it is quite otherwise with me. But nothing is too much for her! It was the same with Lord Spenborough. Not the hardest day’s hunting ever made them anything but sleepy, and excessively hungry; and in London I have often marvelled how they could contrive not to be in the least tired by all the parties, and the noise, and the expeditions,” She smiled, and said apologetically: “I don’t know how it is, but if I am obliged to give a breakfast, perhaps, and to attend a ball as well, there is nothing for it but for me to rest all the afternoon.”

He looked as if he did not wonder at it. “But not Serena?” he asked.

“Oh, no! She never rests during the daytime. That is what makes it so particularly irksome to her to be leading this dawdling life. In London, she would ride in the Park before breakfast, and perhaps do some shopping as well. Then, very often we might give a breakfast, or attend one in the house of one of Lord Spenborough’s numerous acquaintances. Then there would be visits to pay, and perhaps a race-meeting, or a picnic, or some such thing. And, in general, a dinner-party in the evening, or the theatre, and three or four balls or assemblies to go to afterwards.”

“Was this your life?” he asked, rather appalled.

“Oh, no! I can’t keep it up, you see. I did try very hard to grow accustomed to it, because it was my duty to go with Serena, you know. But when she saw how tired I was, and how often I had the headache, she declared she would not drag me out, or permit my lord to do so either. You can have no notion how kind she has been to me. Major Kirkby! My best, my dearest friend!”

Her eyes filled with tears; he slightly pressed her hand, saying in a moved tone: “That I could not doubt!”

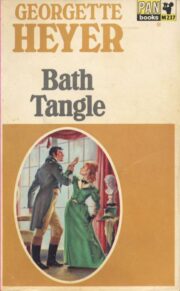

"Bath Tangle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bath Tangle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bath Tangle" друзьям в соцсетях.