“Why—I never missed it,” she said.

He thought he should find out what went on on the second floor, where they kept the people who, as Kristy said, had really lost it. Those who walked around down here holding conversations with themselves or throwing out odd questions at a passerby (“Did I leave my sweater in the church?”) had apparently lost only some of it.

Not enough to qualify.

There were stairs, but the doors at the top were locked and only the staff had the keys. You could not get into the elevator unless somebody buzzed for it to open, from behind the desk.

What did they do, after they lost it?

“Some just sit,” said Kristy. “Some sit and cry. Some try to holler the house down. You don’t really want to know.”

Sometimes they got it back.

“You go in their rooms for a year and they don’t know you from Adam. Then one day, it’s oh, hi, when are we going home. All of a sudden they’re absolutely back to normal again.”

But not for long.

“You think, wow, back to normal. And then they’re gone again.” She snapped her fingers. “Like so.”

In the town where he used to work there was a bookstore that he and Fiona had visited once or twice a year. He went back there by himself. He didn’t feel like buying anything, but he had made a list and picked out a couple of the books on it, and then bought another book that he noticed by chance. It was about Iceland. A book of nineteenth-century watercolors made by a lady traveler to Iceland.

Fiona had never learned her mother’s language and she had never shown much respect for the stories that it preserved—the stories that Grant had taught and written about, and still did write about, in his working life. She referred to their heroes as “old Njal” or “old Snorri.” But in the last few years she had developed an interest in the country itself and looked at travel guides. She read about William Morris’s trip, and Auden’s. She didn’t really plan to travel there. She said the weather was too dreadful. Also—she said—there ought to be one place you thought about and knew about and maybe longed for—but never did get to see.

When Grant first started teaching Anglo-Saxon and Nordic Literature he got the regular sort of students in his classes. But after a few years he noticed a change. Married women started going back to school. Not with the idea of qualifying for a better job or for any job but simply to give themselves something more interesting to think about than their usual housework and hobbies. To enrich their lives. And perhaps it followed naturally that the men who taught them these things would become part of the enrichment, that these men would seem to these women more mysterious and desirable than the men they still cooked for and slept with.

The studies chosen were usually Psychology or Cultural History or English Literature. Archaeology or Linguistics was picked sometimes but dropped when it turned out to be heavy going. Those who signed up for Grant’s courses might have a Scandinavian background, like Fiona, or they might have learned something about Norse mythology from Wagner or historical novels. There were also a few who thought he was teaching a Celtic language and for whom everything Celtic had a mystic allure.

He spoke to such aspirants fairly roughly from his side of the desk.

“If you want to learn a pretty language, go and learn Spanish. Then you can use it if you go to Mexico.”

Some took his warning and drifted away. Others seemed to be moved in a personal way by his demanding tone. They worked with a will and brought into his office, into his regulated, satisfactory life, the great surprising bloom of their mature female compliance, their tremulous hope of approval.

He chose the woman named Jacqui Adams. She was the opposite of Fiona—short, cushiony, dark-eyed, effusive. A stranger to irony. The affair lasted for a year, until her husband was transferred. When they were saying good-bye, in her car, she began to shake uncontrollably. It was as if she had hypothermia. She wrote to him a few times, but he found the tone of her letters overwrought and could not decide how to answer. He let the time for answering slip away while he became magically and unexpectedly involved with a girl who was young enough to be her daughter.

For another and more dizzying development had taken place while he was busy with Jacqui. Young girls with long hair and sandalled feet were coming into his office and all but declaring themselves ready for sex. The cautious approaches, the tender intimations of feeling required with Jacqui were out the window. A whirlwind hit him, as it did many others, wish becoming action in a way that made him wonder if there wasn’t something missed. But who had time for regrets? He heard of simultaneous liaisons, savage and risky encounters. Scandals burst wide open, with high and painful drama all round but a feeling that somehow it was better so. There were reprisals—there were firings. But those fired went off to teach at smaller, more tolerant colleges or Open Learning Centers, and many wives left behind got over the shock and took up the costumes, the sexual nonchalance of the girls who had tempted their men. Academic parties, which used to be so predictable, became a minefield. An epidemic had broken out, it was spreading like the Spanish flu. Only this time people ran after contagion, and few between sixteen and sixty seemed willing to be left out.

Fiona appeared to be quite willing, however. Her mother was dying, and her experience in the hospital led her from her routine work in the registrar’s office into her new job. Grant himself did not go overboard, at least in comparison with some people around him. He never let another woman get as close to him as Jacqui had been. What he felt was mainly a gigantic increase in well-being. A tendency to pudginess that he had had since he was twelve years old disappeared. He ran up steps two at a time. He appreciated as never before a pageant of torn clouds and winter sunset seen from his office window, the charm of antique lamps glowing between his neighbors’ living-room curtains, the cries of children in the park at dusk, unwilling to leave the hill where they’d been tobogganing. Come summer, he learned the names of flowers. In his classroom, after coaching by his nearly voiceless mother-in-law (her affliction was cancer of the throat), he risked reciting and then translating the majestic and gory ode, the head-ransom, the Hofu-olausn, composed to honor King Eric Blood-axe by the skald whom that king had condemned to death. (And who was then, by the same king—and by the power of poetry—set free.) All applauded—even the peaceniks in the class whom he’d cheerfully taunted earlier, asking if they would like to wait in the hall. Driving home that day or maybe another he found an absurd and blasphemous quotation running around in his head.

And so he increased in wisdom and stature—

And in favor with God and man.

That embarrassed him at the time and gave him a superstitious chill. As it did yet. But so long as nobody knew, it seemed not unnatural.

He took the book with him, the next time he went to Meadowlake. It was a Wednesday. He went looking for Fiona at the card tables and did not see her.

A woman called out to him, “She’s not here. She’s sick.” Her voice sounded self-important and excited—pleased with herself for having recognized him when he knew nothing about her. Perhaps also pleased with all she knew about Fiona, about Fiona’s life here, thinking it was maybe more than he knew.

“He’s not here either,” she said.

Grant went to find Kristy.

“Nothing, really,” she said, when he asked what was the matter with Fiona. “She’s just having a day in bed today, just a bit of an upset.”

Fiona was sitting straight up in the bed. He hadn’t noticed, the few times that he had been in this room, that this was a hospital bed and could be cranked up in such a way. She was wearing one of her high-necked maidenly gowns, and her face had a pallor that was not like cherry blossoms but like flour paste.

Aubrey was beside her in his wheelchair, pushed as close to the bed as it could get. Instead of the nondescript open-necked shirts he usually wore, he was wearing a jacket and a tie. His natty-looking tweed hat was resting on the bed. He looked as if he had been out on important business.

To see his lawyer? His banker? To make arrangements with the funeral director?

Whatever he’d been doing, he looked worn out by it. He too was gray in the face.

They both looked up at Grant with a stony, grief-ridden apprehension that turned to relief, if not to welcome, when they saw who he was.

Not who they thought he’d be.

They were hanging on to each other’s hands and they did not let go.

The hat on the bed. The jacket and tie.

It wasn’t that Aubrey had been out. It wasn’t a question of where he’d been or whom he’d been to see. It was where he was going.

Grant set the book down on the bed beside Fiona’s free hand.

“It’s about Iceland,” he said. “I thought maybe you’d like to look at it.”

“Why, thank you,” said Fiona. She didn’t look at the book. He put her hand on it.

“Iceland,” he said.

She said, “Ice-land.” The first syllable managed to hold a tinkle of interest, but the second fell flat. Anyway, it was necessary for her to turn her attention back to Aubrey, who was pulling his great thick hand out of hers.

“What is it?” she said. “What is it, dear heart?”

Grant had never heard her use this flowery expression before.

“Oh, all right,” she said. “Oh, here.” And she pulled a handful of tissues from the box beside her bed.

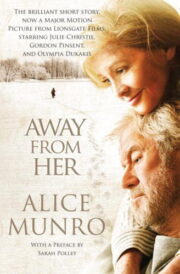

"Away from Her" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Away from Her". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Away from Her" друзьям в соцсетях.