You never quite knew how such things would turn out. You almost knew, but you could never be sure.

She would be sitting in her house now, waiting for him to call. Or probably not sitting. Doing things to keep herself busy. She seemed to be a woman who would keep busy. Her house had certainly shown the benefits of nonstop attention. And there was Aubrey—care of him had to continue as usual. She might have given him an early supper—fitting his meals to a Meadowlake timetable in order to get him settled for the night earlier and free herself of his routine for the day. (What would she do about him when she went to the dance? Could he be left alone or would she get a sitter? Would she tell him where she was going, introduce her escort? Would her escort pay the sitter?)

She might have fed Aubrey while Grant was buying the mushrooms and driving home. She might now be preparing him for bed. But all the time she would be conscious of the phone, of the silence of the phone. Maybe she would have calculated how long it would take Grant to drive home. His address in the phone book would have given her a rough idea of where he lived. She would calculate how long, then add to that time for possible shopping for supper (figuring that a man alone would shop every day). Then a certain amount of time for him to get around to listening to his messages. And as the silence persisted she would think of other things. Other errands he might have had to do before he got home. Or perhaps a dinner out, a meeting that meant he would not get home at suppertime at all.

She would stay up late, cleaning her kitchen cupboards, watching television, arguing with herself about whether there was still a chance.

What conceit on his part. She was above all things a sensible woman. She would go to bed at her regular time thinking that he didn’t look as if he’d be a decent dancer anyway. Too stiff, too professorial.

He stayed near the phone, looking at magazines, but he didn’t pick it up when it rang again.

“Grant. This is Marian. I was down in the basement putting the wash in the dryer and I heard the phone and when I got upstairs whoever it was had hung up. So I just thought I ought to say I was here. If it was you and if you are even home. Because I don’t have a machine obviously, so you couldn’t leave a message. So I just wanted. To let you know.

“Bye.”

The time was now twenty-five after ten.

Bye.

He would say that he’d just got home. There was no point in bringing to her mind the picture of his sitting here, weighing the pros and cons.

Drapes. That would be her word for the blue curtains—drapes. And why not? He thought of the ginger cookies so perfectly round that she’d had to announce they were homemade, the ceramic coffee mugs on their ceramic tree. A plastic runner, he was sure, protecting the hall carpet. A high-gloss exactness and practicality that his mother had never achieved but would have admired—was that why he could feel this twinge of bizarre and unreliable affection? Or was it because he’d had two more drinks after the first?

The walnut-stain tan—he believed now that it was a tan—of her face and neck would most likely continue into her cleavage, which would be deep, crepey-skinned, odorous and hot. He had that to think of, as he dialed the number that he had already written down. That and the practical sensuality of her cat’s tongue. Her gemstone eyes.

Fiona was in her room but not in bed. She was sitting by the open window, wearing a seasonable but oddly short and bright dress. Through the window came a heady, warm blast of lilacs in bloom and the spring manure spread over the fields.

She had a book open in her lap.

She said, “Look at this beautiful book I found, it’s about Iceland. You wouldn’t think they’d leave valuable books lying around in the rooms. The people staying here are not necessarily honest. And I think they’ve got the clothes mixed up. I never wear yellow.”

“Fiona…,” he said.

“You’ve been gone a long time. Are we all checked out now?”

“Fiona, I’ve brought a surprise for you. Do you remember Aubrey?”

She stared at him for a moment, as if waves of wind had come beating into her face. Into her face, into her head, pulling everything to rags.

“Names elude me,” she said harshly.

Then the look passed away as she retrieved, with an effort, some bantering grace. She set the book down carefully and stood up and lifted her arms to put them around him. Her skin or her breath gave off a faint new smell, a smell that seemed to him like that of the stems of cut flowers left too long in their water.

“I’m happy to see you,” she said, and pulled his earlobes.

“You could have just driven away,” she said. “Just driven away without a care in the world and forsook me. Forsooken me. Forsaken.”

He kept his face against her white hair, her pink scalp, her sweetly shaped skull. He said, Not a chance.

Acclaim for Alice Munro

“No one working today can write more convincingly about ‘the progress of love’ than Alice Munro.”

“Alice Munro is the living writer most likely to be read in a hundred years.… Her genius, like Chekhov’s, is quiet and particularly hard to describe, because it has the simplicity of the best naturalism, in that it seems not translated from life, but, rather, like life itself.”

“Munro’s stories are composed with a clarity and economy that make novel-writing look downright superfluous and self-indulgent.”

“[Munro’s] writing never loses its juice, never goes brittle; it also never equivocates or blinks, but simply lets observations speak for themselves.”

“Alice Munro spins tales that show us, again and again, and with wondrous grace, how much can be done in a simple short story.”

“It has been remarked that there is almost always something open-ended, unexplained, or incomplete in Munro’s work. But this deliberate refusal to weave in all the loose threads makes her stories seem more authentic, since this is what real life is like.”

“Munro is the illusionist whose trick can never be exposed. And that is because there is no smoke, there are no mirrors. Munro really does know magic: how to summon the spirits and the emotions that animate our lives.”

“In Munro’s hands, a short story is more than big enough to hold the world—and to astonish us, again and again, with the choices forced upon the human heart.”

“Nothing in a Munro story ever feels contrived…. [She] sings, and her women are heroic. They endure the lives produced by their choices and the fates, and they endure in the mind of the reader.”

“From a markedly finite number of essential components, Munro rather miraculously spins out countless permuta tions of desire and despair, attenuated hopes and cloud bursts of epiphany.”

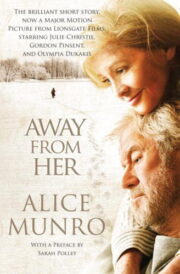

About the Author

Alice Munro grew up in Wingham, Ontario, and attended the University of Western Ontario. She has published more than ten collections of stories as well as a novel, Lives of Girls and Women. During her distinguished career she has been the recipient of many awards and prizes, including three of Canada’s Governor General’s Literary Awards and its Giller Prize, the Rea Award for the Short Story, the Lannan Literary Award, the W. H. Smith Literary Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her stories have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, The Paris Review, and other publications, and her collections have been translated into thirteen languages. Alice Munro and her husband divide their time between Clinton, Ontario, near Lake Huron, and Comox, British Columbia.

"Away from Her" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Away from Her". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Away from Her" друзьям в соцсетях.