She held her hand up, her face darkening. “Don’t say it.”

“Sorry. This is a different world from the one I knew. In my time we took care of women, tried to make things easier for them. I don’t know what to do with you,” he said, studying her face. “I didn’t mean to insult you.”

Her expression softened, though her body still looked stiff as a corset. “I know you mean well, but I’m not a child. Don’t treat me like one. I don’t need another father.”

Like a child? That was nowhere near how he wanted to treat her. After he made sure Brodie had grown bored with his wine tricks, Faelan slipped away from the noise and commotion. Alone, he wandered through the house reliving memories far older than they felt. The library still smelled like a warm fire on a cool night. He could close his eyes and see his family gathered around the hearth listening to one of his father’s wild tales of his warrior days, while Tavis and Ian poked at each other when no one was looking. The furniture had changed, and the kitchen had modern appliances like in Bree’s house, but even bigger, to feed all the warriors coming through. The solid oak table was still there, with Ian’s initials carved under the edge.

Several bedrooms had been converted into fancy bathrooms like Bree’s. His mother would’ve loved it. His father too, who’d love to sing in the tub, his voice booming so loud they could hear him outside. In Faelan’s time, most of the bedrooms had tubs for bathing, but the water had to be carried by hand. One room had a basin and a water closet of sorts, but most of the time they used the privy out back.

He paused when he reached the bedroom he’d shared with his brothers, running a hand over the gouge in the wooden door. Tavis had thrown a knife at Ian for teasing him about Marna, the blacksmith’s daughter, who always gave Tavis extra sweeties. When their father saw the gouge, Faelan claimed he’d used the door for target practice, but his father wasn’t fooled, and all three of them had gotten their hides tanned.

Faelan opened the door, wondering if any of his things had survived. His mom had kept the room unchanged, even after he and his brothers moved out. It was painted yellow now. The curtains and quilt were different, but his old iron bed was the same. He opened the closet. None of his belongings were here. Slipping off his boots, he lay on the bed that was too small. He pulled the smooth stone from his pocket, rubbing his thumb over it as the distant sounds of laughter faded and exhaustion brought sleep.

The wind whipped his hair against his face as Faelan galloped ahead of the storm. He glanced over his shoulder and saw Tavis on the hill closing in, but Ian hadn’t caught up. Faelan nudged Nandor to go faster. The lucky stone would be his. A tree branch smacked his chest, wiping the triumph from his face. He righted himself as Tavis sped ahead with a victory cry.

“The stone’s mine,” Tavis shouted over the wind.

Faelan jumped to the ground outside the stables, leading Nandor inside, while Tavis held the door.

“Where’s Ian?” Faelan asked, looking into the storm.

“I thought he’d catch up by the burn.” Tavis put his horse in the stall as Faelan watched from the open door for a sign of their brother. Two more crashes sounded. Faelan swung onto Nandor’s back. “You’re not going back out there,” Tavis said, glancing at the sky.

The next flash brought an image of a tiny casket being lowered into the ground. “I have to.”

“You’re daft. It’s lightning like the devil out there. We’ll get Father. Ian probably saw the storm coming and went to the cabin.”

“I can’t leave him out there. He’s my responsibility. I’m the oldest.”

“It’s not your fault, Faelan,” Tavis said, and they both knew he wasn’t talking about Ian. “You tried to save him. I’m the one who didn’t get there in time. I’m getting Father—”

“No,” Faelan shouted. “I’ll take care of it.” He rode out the open door into the storm, leaving Tavis frowning after him.

Nandor’s hoofs splattered mud as they raced across the back field. Faelan wished he’d never suggested this game. He wasn’t a kid anymore. In two years, he would start training. He should’ve known better, read the weather beforehand. Faelan rounded the corner of the orchard and stopped.

Ian lay face down in the dirt, his horse nowhere to be seen. Faelan jumped off Nandor and sprinted to his brother. “Ian?” He crouched over him, but Ian didn’t move. Faelan pulled Ian’s kilt over his backside and rolled him over, putting his ear to Ian’s chest. His heartbeat was strong. “Come on, Ian.” Faelan shook his brother, but he didn’t move. A horse whinnied behind him. He turned and saw Tavis jump from his horse and run toward them. He should have known Tavis would never stay behind. “His horse must have thrown him,” Faelan said.

Tavis nodded.

Together they carried Ian to where Nandor stood. Faelan whistled, and the young stallion straightened his forelegs and leaned down. They laid Ian across Nandor’s back, and Faelan jumped on behind him, adjusting Ian so he was leaning back in Faelan’s arms. Tavis mounted, and they hurried home. Faelan gripped his brother’s lanky body as he urged Nandor to go faster.

Ian roused in sight of the house. He tried to move, but Faelan held him still.

“Hold on. We’re almost home.” His father ran across the field toward them, his face black as the sky.

“What happened?” he yelled as they lifted a grumbling Ian off the horse.

“He fell.”

“You should’ve come for me. Why do you try to do everything yourself? There’s no shame in asking for help, lad. You’re not God. All we need is for your mother to lose another son.”

Faelan opened his eyes and looked at his bedroom. Loneliness settled like a heavy fog. He squeezed the stone he held. He should’ve given it to Tavis. He’d won it fair and square.

Faelan stuck the stone in his pocket and shoved his feet into his boots. Crossing to the small balcony, he climbed over and dropped to the ground, landing lightly, like a cat, almost hitting a huge elderberry bush in the same place where he’d helped his mother plant hers. He sprang up and ran. Whoever was watching the cameras would see him, but he needed space to think. He filled his lungs with the night air, thick with memories, and felt the breath of others who’d walked here and gone.

He moved forward without thinking, letting his feet lead the way. He passed the stables, the trees he’d climbed as a lad, fields where he’d raced with Nandor, and he headed for the knoll. The crumbling wall stood as it had for centuries. Faelan swallowed the lump in his throat as he stepped inside. The markers stood in silence, their occupants undisturbed by evil or wind or cold.

He moved between the headstones, past grandparents and great-grandparents, generations of Connors who slept here. There hadn’t been so many graves then. In the corner, he found them, their markers stained with age. Ian dead in 1863. Beside him were his wife and three sons, two of them born on the same day. Twins. Then Alana, who’d lived until 1925, and her husband. A small headstone lay alongside them.

Faelan, beloved son of Alana and Robert Nottingham, eleven months old.

Alana had named a son after him. Faelan’s throat tightened. Beside the tiny grave were two more sons and three daughters born to his sister. Next was Tavis’s marker. Dead in 1860, buried at sea, the year Faelan had been locked in the time vault. Why hadn’t they told him? Behind his brothers’ and sister’s graves, sheltered under an old tree, Faelan found his father and mother. Aiden and Lena Connor. His mother had lived until age fifty-three. His father had died the same year as Tavis. Between his parents lay Liam’s small grave.

Memories welled like a dam and broke free. A giggling Alana, smelling of apples and sunshine. His brothers in swordplay as their father corrected their form. Dirt smudges on his mother’s cheery face as he helped her plant the elderberry bush. Liam, his limp body drenched with water when they pulled him from the well. Gone. They were all gone.

He thought about how many others had grieved for a father or brother or son who’d died in a war he failed to stop. A wife mourning a husband who’d never return. A mother weeping over a son who’d died far too young. Another who’d killed his brother for a cause that was nothing more than a distraction for Druan. Families destroyed, lives ruined, because he hadn’t stopped Druan in time. The lonely wail of a dog pulled Faelan’s pain inside out. He moved back to where his brothers lay and placed the white stone on Tavis’s grave.

Chapter 24

Bree reached for the telephone and let out a delicate belch. The haggis. Her stomach rolled. She’d been too distracted watching Faelan’s reunion with his family—and all those men wearing kilts—to notice what was on the plate Brodie handed her. Maybe she just dreaded the thought of facing all those warriors and admitting she’d almost married an ancient demon. Or it could have been the wine. She’d had only one glass, but it felt like four. Faelan had disappeared earlier. It was some consolation that she’d seen Sorcha wrapped around another man downstairs, but with Sorcha’s flirting and Faelan’s out-of-control lust, it was a matter of time. If Duncan didn’t kill Sorcha first. He obviously saw something in the witch that no one else did.

Laughter drifted from below as Bree dialed her mother’s number. Coira had told Bree to make use of the house phone. Her mother didn’t answer. She must be out with Sandy. Bree checked her voice mail next. There was one message.

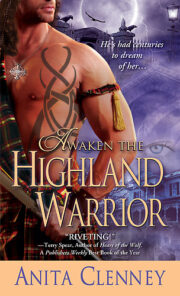

"Awaken the Highland Warrior" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Awaken the Highland Warrior". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Awaken the Highland Warrior" друзьям в соцсетях.