“This is Faelan.” It wouldn’t do any good to deny the conclusion to which her mother had joyfully leapt.

“Faelan Connor, ma’am,” he said, gallantly tipping his head, a rather absurd-looking gesture with him in his underwear, holding a dagger. “I apologize. I thought you were a burglar.”

“Protective. How nice,” she said, glancing at his underwear again. “Are you staying here?”

“Uh…” Faelan threw a panicked look at Bree.

“For the moment. Why didn’t you tell me you were coming?” Bree asked.

“I mentioned it on the phone, dear. I’d planned to get a hotel, but there’s not a vacancy to be had. Some sort of conference in town.” She glanced at the house. “Not too bad.” She crinkled her nose. “But I think you went a bit heavy on the perfume.”

“The bottle spilled. What about your allergies and all this dust?”

“I’ll be here for only a day or two. I’m on my way to meet Sandy. You remember my friend. She’s coming to Florida for a visit, but she hates to drive alone, and she refuses to fly. Can you believe someone in this day and age afraid of airplanes?” she asked Faelan. “I’m going to pick her up. You have clean sheets, don’t you, Briana?”

“I, uh… yes.” The problem was, she didn’t have a bed to put them on, and Bree was certain her mother had never slept on a sofa. “You can have my room.”

“Where will you sleep, darling?” She tossed a loaded glance from Faelan to Bree.

“Uh, the couch.”

She held her arm out to Faelan. “Well then, that’s settled. Faelan, would you be a dear and bring my suitcase? In the morning, we’ll have a little chat, get to know one another, and I’ll tell you some of the cutest stories about Briana.”

Faelan handed Bree his dagger and took the suitcase in one hand, her mother’s arm in the other, and the two of them walked down the hall to the bedroom.

“She was an adorable child, but had the wildest imagination. She was terrified of the graveyard. Had horrible nightmares until that nasty Reggie locked her inside the crypt. After that, we couldn’t keep her away. She had picnics right there next to the headstones, with her little tea set and blanket and her ragged old panda bear, talking to thin air. She had an imaginary friend,” Orla stage-whispered.

An imaginary friend. That might explain why she sometimes felt like someone else was living inside her, had thoughts she knew weren’t her own.

For someone who’d never seen a ghost, she damned well felt haunted.

***

“And when she was twelve she wanted to be a deep-sea treasure hunter,” her mother told Faelan as they toured the house the next morning.

They were lucky no demons showed up during the night. The perfume probably kept them away. Bree had caught Faelan in the kitchen, staring out into the backyard, his hand clasped to his talisman. Standing guard.

“She was certain Atlantis was down there somewhere. Remember that, dear?” Bree’s mother asked as they entered the room where Bree had been sanding the floor.

“How could I forget?” When you keep reminding me. How she could’ve been born to Orla Kirkland was as much a mystery as how Faelan was alive and breathing when he should be nothing but bones. Her mother never pumped her own gas. She got her nails done every week and a half on the dot, and she wouldn’t dream of charging out to rescue a man for any reason whatsoever. This apple not only fell far from the tree, but it rolled down the hill and bounced into another town. Bree couldn’t imagine her mother giving birth to one baby, much less twins.

“You finished the floor, Briana. I thought your sander broke.”

“It did.” Bree stared at the finished floor. Her mouth dropped. She looked at Faelan’s eager smile, and her eyes stung. “You finished it for me? By hand?”

“Oh, my.” Orla beamed and dabbed at one eye.

“Thank you,” Bree whispered, squeezing his arm. They headed to the living room where her mother continued her embarrassing stories, and Faelan listened with rapt attention while Bree dug through a box of her old things her mother had brought. She picked up Emmy, the stuffed panda she’d had since she was a child. It was missing one eye and its black and white body was worn and ratty from being held through too many bad dreams.

“But she suffers from sea sickness, like Layla—” Her mother pressed her lips together and brushed at invisible lint on her skirt.

“Aunt Layla got seasick, too?” Bree asked.

“Lots of Kirklands do, dear. Even your grandmother did. Remember how sick she got on that cruise? I’ve been meaning to ask, did you find out what she wanted to talk to you about before she died? She called the house the day before, trying to find you, but I wasn’t there. Her message sounded strange. I tried to call her back, but… I haven’t asked before now, because I didn’t want to upset you, with everything going on.”

Her mother was almost rambling. Bree rambled when she was nervous. Orla Kirkland never rambled. It must be the wedding bells clanging in her head.

“She left a message, but by the time I got it, it was too late.”

“Perhaps she wanted to say good-bye. I think she knew she was nearing the end. She seemed troubled the last time I talked to her. Maybe she mentioned something in her journal. I don’t suppose you’ve found it,” she added, picking at her skirt again. As if lint would dare attach itself to Orla Kirkland’s clothing.

“No.” Why did her mother care? She’d never been interested in anyone’s journal before. “Besides working on the renovations, I’ve been busy cleaning up the graveyard and watching the archeologists dig.” Bree hadn’t mentioned finding Isabel’s journal. She hadn’t wanted to share her secret, not even with her mother and her best friend. Why had she shared it with Faelan?

“Archeology digs and graveyards. You should be thinking about marriage and children,” she said, casting a desperate glance at Faelan.

Dead people weren’t so bad. At least they didn’t judge.

“Her grandmother’s side of the family, that’s where she gets her adventurous spirit,” Orla said to Faelan. “Even in kindergarten. Oh, the drawings she brought home. Aliens one day, monsters and angels the next. Your old sketchbook is in there, Briana. I thought you might want it.”

Bree spotted the book at the bottom of the box. A chill slid over her body as her mother’s voice faded. She stared at the cover, hands heavy with dread. Slowly she opened it. The first sketch was of the house and graveyard with its leaning headstones. The crypt sat in the center, larger than everything else. The tree hovered over it, its blackened branches stretching out like claws. She shivered and slammed the book shut. She shoved it back in the box and looked up to see Faelan watching her. Bree realized she had Emmy gripped tight against her chest. She put the panda back in the box as her mother droned on about her recklessness.

“Thank God the nightmares stopped after the crypt. I wish the recklessness had. The migraines she gave me. All through middle school and high school, she was always looking for some relic or treasure. You’d have thought she was on a quest. There was the gold-panning fiasco in college… I don’t know what she was thinking, traveling alone out in the middle of nowhere looking for gold that didn’t exist. But Lord, were there snakes.”

Faelan cocked one brow. “Snakes?”

“Her grandmother and I thought she would die. The doctor said she should have died. He’d never seen anyone recover from so many poisonous bites at once. She fell into a den of them. Cobras.” Orla gave an elegant shudder. “But she always heals fast. Her cousin Reggie used to say she was indestructible. She fell a lot, you know.”

“Aye,” Faelan said, the edge of a grin peeking out of his sexy mouth. “She still does.”

“They were copperheads, Mother. They don’t have cobras in Colorado. And if the medevac helicopter hadn’t flown in to get me, they wouldn’t have found Todd.”

“Who’s Todd?” Faelan asked, grin disappearing as his eyebrows gathered into a glare.

“Your disasters usually do end well.” Orla sighed. “For someone else. The poor child was hiking with his uncle,” she told Faelan. “They got caught in a rockslide, and the uncle died. The boy had a broken leg. The cell phone was buried with the uncle, and there wasn’t a soul around for thirty miles. He took shelter in a cave. He’d been there two days without food or water. When he heard the rescue helicopter, he crawled out and waved his shirt. The pilot saw him. Sweet boy. Bree visits him every year.”

“Was that the cave where she broke her ankle?”

“The cave,” her mother drawled in horror, wrapping a manicured hand around Faelan’s arm. “That was a different time. They had to cut the bat out of her hair. Have you ever heard of a bat strangling in someone’s hair? It’s a wonder she didn’t fall off the cliff. There she was, hanging from a tiny branch with a dead bat in her hair.”

“Damnation.”

“It was a small cliff,” Bree mumbled, glad her mother didn’t know half of her adventures. Too bad her sixth sense didn’t work in her own life.

“Her father, rest his soul, should’ve put his foot down. He bought her the most beautiful dolls, but all she wanted to do was hunt for treasure and explore caves, so he trekked around the countryside after her, metal detecting, bringing home twisted bits of metal they called coins. And the Civil War reenactments, egad! All those men lying on the ground pretending to be dead. Just not healthy for an eight-year-old. It’s her specialty now, the Civil War.”

The laughter left Faelan’s eyes like a candle doused by a wave.

“Mother, you’re going to make Faelan think I’m unstable.” She gave her mother a you’re-not-helping stare.

“Oh, but she’s not nearly as impulsive now,” her mother said, tightening her grip on Faelan’s arm. “She has quite a reputation as an antiquities expert. Her knowledge is very much in demand. She authenticated a dagger last year for a prince. And since most of her work is consulting, it won’t interfere with having children. You do like children?”

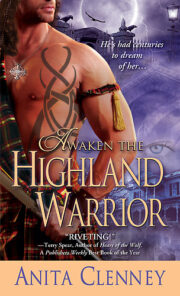

"Awaken the Highland Warrior" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Awaken the Highland Warrior". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Awaken the Highland Warrior" друзьям в соцсетях.